Overview

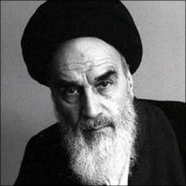

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was the founder and first supreme leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran. In that role, Khomeini created or influenced multiple violent extremist groups, including Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Lebanese political-terror hybrid Hezbollah. Even after his death in 1989, Khomeini’s views and philosophies, collectively known as Khomeinism, have continued to guide the Iranian regime and its terrorist proxies.Raymond H. Anderson, “Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader,” New York Times, June 4, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/04/obituaries/ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-89-the-unwavering-iranian-spiritual-leader.html;

Don A. Schanche, “Ayatollah Khomeini Dies at 86: Fiery Leaders Was in Failing Health Following Surgery,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1989, http://articles.latimes.com/1989-06-04/news/mn-2499_1_ayatollah-khomeini-dies-power-struggle-jurisprudent;

“The Imam’s Background,” The Institute For Compilation and Publications of Imam Khomeini’s Works, August 16, 2011, http://en.imam-khomeini.ir/en/n3123/Biography/The_Imam_s_Background;

Amal Saad-Ghorayeb, “Khamenei and Hezbollah: Leading in Spirit,” Al-Akbar English, August 8, 2012, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/10894.

Various records place Khomeini’s birth year as early as 1900 and as late as 1903. Born in Khomein, Iran, Khomeini was raised by his aunt’s family after the death of his father and his mother’s relocation to Tehran.Raymond H. Anderson, “Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader,” New York Times, June 4, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/04/obituaries/ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-89-the-unwavering-iranian-spiritual-leader.html;

“The Imam’s Background,” The Institute For Compilation and Publications of Imam Khomeini’s Works, August 16, 2011, http://en.imam-khomeini.ir/en/n3123/Biography/The_Imam_s_Background.

In the early 1960s, Khomeini began to publicly criticize Iranian leader Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, accusing his “un-Islamic” government of acting at the behest of the United States, Great Britain, and Israel. Khomeini’s message began to gain momentum, leading government forces to arrest him in 1962 and 1963.“Ayatollah Khomeini (1900-1989),” BBC, accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml;

Raymond H. Anderson, “Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader,” New York Times, June 4, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/04/obituaries/ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-89-the-unwavering-iranian-spiritual-leader.html.The Iranian government finally expelled Khomeini from the country in November 1964 after he protested the exemption of U.S. military members from Iranian legal jurisdiction.Raymond H. Anderson, “Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader,” New York Times, June 4, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/04/obituaries/ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-89-the-unwavering-iranian-spiritual-leader.html.

Following his expulsion from Iran, Khomeini moved briefly to Turkey and then to Iraq, where he lived for 13 years while continuing to speak out against the shah.“Ayatollah Khomeini (1900-1989),” BBC, accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml;

“Exile to Paris,” Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini’s Works, August 16, 2011, http://en.imam-khomeini.ir/en/n2276/Biography/Exile_to_Paris. In Iraq in 1970, Khomeini wrote Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist, in which he outlined his modern interpretation of the ninth-century Shiite concept of vilayat-e faqih, or guardianship of the Islamic jurist. Traditionally, the philosophy called for a single Islamic jurist to be endowed with religious authority while leaving political authority in the hands of the state, though scholars disputed the exact division of power. Khomeini used the concept to justify his vision of a single cleric overseeing Iran’s religious, military, and governmental sectors in order to ensure compliance with “divine law,” since only then could such a government be “accepted by God on Resurrection Day,” as he wrote in Unveiling the Mysteries.“Islamic Government: Governance of the Jurist,” Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project, accessed March 20, 2017, https://www.al-islam.org/islamic-government-governance-of-jurist-imam-khomeini;

Raymond H. Anderson, “Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader,” New York Times, June 4, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/06/04/obituaries/ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-89-the-unwavering-iranian-spiritual-leader.html. Iran would eventually enshrine Khomeini’s interpretation of vilayat-e faqih into its 1979 constitution, thereby justifying the continued authoritarian role of the country’s supreme leader.“Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Constitution.com, accessed March 20, 2017, http://constitution.com/constitution-of-the-islamic-republic-of-iran/.

The Baha’is are not a genuine religion, and have no place in Iran.

In September 1978, the Iranian government imposed martial law after anti-shah riots broke out across Iran.“Iran profile – timeline,” BBC News, December 20, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14542438. The following month, Iraq expelled Khomeini amid pressure from the Iranian government. Khomeini subsequently relocated to Paris after being denied entry to Kuwait.“Exile to Paris,” Institute for Compilation and Publication of Imam Khomeini’s Works, August 16, 2011, http://en.imam-khomeini.ir/en/n2276/Biography/Exile_to_Paris. On January 12, 1979, while in Paris, Khomeini helped to form the Islamic Revolutionary Council with hardline Iranian religious leaders in Iran. The council oversaw protests against the shah and later appointed Khomeini’s revolutionary government.“Ayatollah Khomeini (1900-1989),” BBC, accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml.

Khomeini returned to Iran on February 1, 1979—weeks after the shah had left the country for cancer treatment.“Ayatollah Khomeini (1900-1989),” BBC, accessed March 17, 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/khomeini_ayatollah.shtml. By this time, violent demonstrations against the government had broken out across Iran. Upon his arrival in Tehran, Khomeini addressed revolutionary supporters and issued a warning to shah-appointed Prime Minister Shapour Bakhtiar: “If you do not surrender to the nation, the nation will put you in your place.” Khomeini promised supporters he would form a new Islamic government and draft a new constitution.Muhammad Sahimi, “The Ten Days That Changed Iran,” Frontline, February 3, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/02/fajr-10-days-that-changed-iran.html.

Khomeini quickly worked to coopt Iranian political leaders and military forces. On February 2, 1979, Khomeini called on Iran’s armed forces to join the Revolutionary Council. The following day, Tehran’s mayor, Javad Shahrestani, tendered his resignation to the shah’s government and was asked by Khomeini to serve in the new Islamic Republic. Khomeini also met with senior Iranian religious leaders to convince them to support his revolution. On February 5, the last of Iran’s parliament resigned and Khomeini appointed a new prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan.Muhammad Sahimi, “The Ten Days That Changed Iran,” Frontline, February 3, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/02/fajr-10-days-that-changed-iran.html.

Fighting broke out across Iran between protesters, military forces still loyal to the shah, and military forces who had defected to Khomeini.Muhammad Sahimi, “The Ten Days That Changed Iran,” Frontline, February 3, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/02/fajr-10-days-that-changed-iran.html. On February 10, 1979, the beleaguered Iranian government ordered the SAVAK, Iran’s secret police, to arrest Khomeini and 200 others, including journalists and leftists. But pro-Khomeini members of the SAVAK alerted Khomeini, resulting in intensified clashes between pro-Khomeini and pro-regime supporters. The following day, Khomeini called on a group of Iranian soldiers to “act contrary” to the oath they swore to the shah’s government.Muhammad Sahimi, “The Ten Days That Changed Iran,” Frontline, February 3, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/02/fajr-10-days-that-changed-iran.html.

On February 11, 1979, fighting between Khomeini’s followers and Iranian forces left more than 220 people dead. In response, Iran’s armed forces declared their neutrality in the conflict, immediately leading Khomeini and his proto-Islamic Republic to declare victory in deposing the shah’s government.Muhammad Sahimi, “The Ten Days That Changed Iran,” Frontline, February 3, 2010, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/tehranbureau/2010/02/fajr-10-days-that-changed-iran.html. In late March 1979, Iran held a two-day national referendum deciding whether to transform Iran into Khomeini’s vision of an Islamic republic. A clear majority—97 percent—of Iranians voted in Khomeini’s favor, and on April 1, 1979, Khomeini declared the new Islamic Republic of Iran a “government of God.”“Iran profile – timeline,” BBC News, December 20, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14542438;

Gregory Jaynes, “Khomeini Declares Victory in Vote For a ‘Government of God’ in Iran,” New York Times, April 2, 1979, http://www.nytimes.com/1979/04/02/archives/khomeini-declares-victory-in-vote-for-a-government-of-god-in-iran.html?_r=0. That December, Iran passed a new constitution and named Khomeini the supreme leader.Pranay B. Gupte, “Member of Iranian Minority Says Khomeini’s Charter Is ‘Not for Us,’” New York Times, December 5, 1979, http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9504E4DB1438E732A25756C0A9649D946890D6CF.

Vilayat-e faqih is enshrined in Iran’s constitution.

Khomeini and his successor Ali Khamenei have utilized the concept of vilayat-e faqih to maintain the loyalty of Iranian military forces and Iranian-backed extremist movements. In the first months after the 1979 Iranian revolution, before its existence was enshrined in law, the IRGC operated as a militant activist network loyal to Khomeini, helping to stamp out dissident currents within the revolutionary movement.Afshon P. Ostover, Guardians of the Islamic Revolution: Ideology, Politics, and the Development of Military Power in Iran, 1979-2009, University of Michigan, 2009, 50-52. Since its founding, the IRGC has answered directly to the Iranian supreme leader and is tasked with preserving the Islamic government.Babak Dehghanpisheh, “Iran Guards Wield Electoral Power behind Scenes,” Reuters, June 4, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/06/04/us-iran-election-guards-idUSBRE9530V120130604. In 1980, Khomeini’s government created the Basij militia, a paramilitary organization to enforce obedience domestically. Incorporated into the IRGC in 2007, the Basij has carried out widespread human rights abuses in Iran, notoriously during the 2009 protests against the contested presidential elections when its members attacked student dormitories and assaulted protesters.Frederic Wehrey et al., The Rise of the Pasdaran: Assessing the Domestic Roles of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (Santa Monica, Arlington, and Pittsburgh: RAND Corporation, 2009), 33, http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2008/RAND_MG821.pdf;

“IRGC’s Basij Paramilitary Trains Special Battalions for Crackdown on Potential Protests,” International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, February 24, 2014, http://www.iranhumanrights.org/2014/02/basij-battalions/.

Under Khomeini’s direction in the early 1980s, the IRGC provided funding, training, and weaponry to a group of Shiite militants in Lebanon that would emerge as Hezbollah in 1982.Jonathan Masters and Zachary Laub, “Hezbollah (a.k.a. Hizbollah, Hizbu’llah),” Council on Foreign Relations, January 3, 2014, http://www.cfr.org/lebanon/hezbollah-k-hizbollah-hizbullah/p9155. That year, the predecessor to Hezbollah’s Shura Council sent a delegation to Tehran to brief Khomeini on the group’s activities. According to an account given by Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah, Khomeini told Hezbollah to “rely on God,” and “spoke of [future] victories.”Amal Saad-Ghorayeb, “Khamenei and Hezbollah: Leading in Spirit,” Al-Akbar English, August 8, 2012, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/10894. Hezbollah pledged its loyalty to Khomeini in its 1985 manifesto, which explicitly states its compliance to the dictates of “one leader, wise and just, that of our tutor and faqih (jurist) who fulfills all the necessary conditions: [Ayatollah] Ruhollah Musawi Khomeini.”“An Open Letter: The Hizballah Program,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 1, 1988, http://www.cfr.org/terrorist-organizations-and-networks/open-letter-hizballah-program/p30967.

Khomeini’s early support for Hezbollah was but one manifestation of his antipathy toward Israel. In August 1979, Khomeini declared the first Al Quds Day—the Arabic word for Jerusalem—on the last Friday of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan to be an annual, nation-wide protest against Israel.“Quds Days,” United Against Nuclear Iran, accessed March 21, 2017, http://www.unitedagainstnucleariran.com/quds-day. Today, Iran and its proxies annually mark Al Quds Day with protests and rallies, frequently accompanied by chants of “Death to Israel.”Siavash Ardalan, “Iran's 'Jerusalem Day': Behind the rallies and rhetoric,” BBC News, August 2, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-23448932.

I once again remind everyone of the danger of the prevalent, festering and cancerous Zionist tumor in the body of Islamic countries.

Khomeini’s hostility toward Israel was overshadowed only by his hatred for the United States, which he blamed for interfering in domestic Iranian affairs, including through support of the shah’s regime. Khomeini’s anti-American stance fueled Iranian hostilities toward the United States, such as in November 1979 when Iranian students attacked the U.S. embassy in Tehran. The students took 90 people hostage, including 66 Americans, and demanded the shah’s extradition from the United States to Iran for trial. Khomeini immediately praised the students’ actions. After the shah’s death in July 1980, Khomeini demanded that in exchange for the hostages, the United States unfreeze Iranian assets and transfer the shah’s U.S.-based property and wealth to the Iranian government. Throughout 1979 and 1980, the protesters released non-American hostages, female and African-American hostages, and eventually one ill American hostage.D. Parvaz, “Iran 1979: the Islamic revolution that shook the world,” Al Jazeera, February 11, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/01/iran-1979-revolution-shook-world-2014121134227652609.html;

“Iran Hostage Crisis Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated October 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/15/world/meast/iran-hostage-crisis-fast-facts/;

Susan Chun, “Six things you didn’t know about the Iran hostage crisis,” CNN, last updated July 16, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/27/world/ac-six-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-iran-hostage-crisis/.

The remaining 52 American hostages were released on January 21, 1981, one day after Iran and the United States signed the Algiers Accords.D. Parvaz, “Iran 1979: the Islamic revolution that shook the world,” Al Jazeera, February 11, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2014/01/iran-1979-revolution-shook-world-2014121134227652609.html;

“Iran Hostage Crisis Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated October 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/15/world/meast/iran-hostage-crisis-fast-facts/;

Susan Chun, “Six things you didn’t know about the Iran hostage crisis,” CNN, last updated July 16, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/27/world/ac-six-things-you-didnt-know-about-the-iran-hostage-crisis/. As stipulated in the accords, the United States agreed “not to intervene, directly or indirectly, politically or militarily” in Iranian affairs in exchange for the hostages’ release. The United States also agreed to release frozen Iranian assets to a third party.“Text of Agreement Between Iran and the U.S. to Resolve the Hostage Situation,” New York Times, January 20, 1981, http://www.nytimes.com/1981/01/20/world/text-of-agreement-between-iran-and-the-us-to-resolve-the-hostage-situation.html?pagewanted=all. The agreement, however, did little to assuage Khomeini’s ill will toward the United States, which he continued to refer to as the “great Satan.” In his last will and testament in 1989, Khomeini called the United States “the foremost enemy of Islam,” casting it as the root cause of Iran’s economic and political troubles and the leader of an international anti-Islamic front.“In The Name of God The Compassionate, the Merciful,” Al Seraj, accessed June 19, 2014, http://www.alseraj.net/maktaba/kotob/english/Miscellaneousbooks/LastwillofImamKhomeini/occasion/ertehal/english/will/lmnew1.htm.

We must all be prepared... [to] fight against America and its lackeys.

Khomeini regarded the Islamic Republic as the guardian of Islam against the secular world. This belief was notoriously exhibited in Khomeini’s 1989 fatwa ordering the death of British-Indian novelist Salman Rushdie for his novel The Satanic Verses. According to Khomeini, the novel—inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad—ran counter to the tenets of Islam, Muhammad, and the Quran.Sheila Rule, “Khomeini Urges Muslims to Kill Author of Novel,” New York Times, February 15, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/04/18/specials/rushdie-khomeini.html. Days after Khomeini issued the fatwa, Rushdie publicly apologized for “the distress that [his] publication has occasioned to sincere followers of Islam.”Steve Lohr, “Rushdie Expresses Regret to Muslims for Book’s Effect,” New York Times, February 19, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/books/99/04/18/specials/rushdie-regret.html. Khomeini promptly rejected the apology, urging Muslims around the world to “send [Rushdie] to hell.”Michael Ross, “From the archives: Khomeini Renews Call for Death of Rushdie,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 1989, http://articles.latimes.com/1989-02-20/world/la-fg-iran-archive-1989feb20_1_salman-rushdie-ayatollah-ruhollah-khomeini-satanic-verses. Khomeini’s successor, Ali Khamenei, announced in 2005 that the fatwa ordering Rushdie’s death remained in effect.Independent, “Iranian state media renew fatwa on Salman Rushdie,” USA Today, February 23, 2016, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2016/02/23/iranian-state-media-renew-fatwa-salman-rushdie/80790502/. In February 2016, 40 Iranian state-run media outlets offered a $600,000 joint reward for Rushdie’s murder.Independent, “Iranian state media renew fatwa on Salman Rushdie,” USA Today, February 23, 2016, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2016/02/23/iranian-state-media-renew-fatwa-salman-rushdie/80790502/. Affiliated with Iran’s supreme leader, the Iranian charity 15 Khordad Foundation has maintained a multi-million-dollar bounty on Rushdie since 1989. In 2012, the foundation raised its reward to $3.3 million and promised the full sum would be immediately paid to whoever kills Rushdie. The U.S. government levied sanctions on the foundation in October 2022 in the aftermath of an August 12, 2022, attack on Rushdie in Chautauqua, New York, by suspect Hadi Matar.“Treasury Sanctions Iranian Foundation Behind Bounty on Salman Rushdie,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 28, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1059; Steven Vago and Ben Kesslen, “Salman Rushdie attacker praises Iran’s ayatollah, surprised author survived: jailhouse interview,” New York Post, August 17, 2022, https://nypost.com/2022/08/17/alleged-salman-rushdie-attacker-didnt-think-author-would-survive/.

Khomeini died on June 3, 1989. The following day, Ali Khamenei was named Iran’s supreme leader.“Iran profile – timeline,” BBC News, December 20, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14542438.< Khomeini remains a revered figure among Shiite Muslims internationally, and tens of thousands of people reportedly attend annual ceremonies at Khomeini’s tomb in Tehran.“Revamped Khomeini Shrine Shocks Even His Fans,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, May 29, 2015, http://www.rferl.org/a/iran-khomenei-shrine-shocks-supporters-lavish/27043433.html;

Ramin Mostaghim and Nabih Bulos, “Iran marks 25th anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini's death, knocks U.S.,” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 2014, http://www.latimes.com/world/asia/la-fg-iran-anniversary-khomeini-death-20140604-story.html. Khomeini’s philosophies continue to resonate among Shiite extremists. Iraqi Shiite militias such as the Badr Organization, Asaib Ahl al-Haq, and Kata’ib Hezbollah have pledged allegiance to the Iranian regime and Khamenei out of duty to vilayat-e faqih.Ned Parker, Babak Dehghanpisheh, and Isabel Coles, “Special Report: How Iran's military chiefs operate in Iraq,” Reuters, February 24, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-committee-specialrepor-idUSKBN0LS0VD20150224;

Richard R. Brennan et al., eds., Ending the U.S. War in Iraq: the Final Transition, Operational Maneuver, and Disestablishment of United States Forces-Iraq (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2013), 138-139, http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR232/RAND_RR232.pdf;

Ned Parker and Raheem Salman, “In defense of Baghdad, Iraq turns to Shi'ite militias,” Reuters, June 14, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/06/14/us-iraq-security-volunteers-idUSKBN0EP0O920140614.

Associated Groups

- Extremist entity

- Islamic Republic of Iran

- Type(s) of Organization:

- Ideologies and Affiliations:

- Position(s):

- Former supreme leader