Fact:

On April 3, 2017, the day Vladimir Putin was due to visit the city, a suicide bombing was carried out in the St. Petersburg metro, killing 15 people and injuring 64. An al-Qaeda affiliate, Imam Shamil Battalion, claimed responsibility.

“Denounce your work colleagues, neighbors or acquaintances today and collect instant cash. Help us to remove these problem Germans from the economy and public office.”

With these provocative words, the German left-wing activist art collective Center for Political Beauty (Zentrum für politische Schöhnheit or ZPS) launched the online campaign “SOKO Chemnitz” in early December 2018 and caused a massive controversy within German society.

On August 26, 2018, police arrested two refugees—from Syria and Iraq—suspected of fatally stabbing a German man in Chemnitz. The incident triggered far-right extremists and neo-Nazis to riot in the streets and attack immigrants. Subsequent police investigations of far-right suspects allegedly involved in the riot proved to be difficult and cumbersome. Political parties were unprepared for the size and ugliness of the far-right show of force and wound up blaming one another for the degree of xenophobia it revealed.

On December 3, 2018, ZPS launched its online campaign SOKO Chemnitz by uploading about 7,000 pictures of Chemnitz protestors, and called upon the German society to identify the individuals and engage in the group’s efforts of “denazification.” On the website “soko-chemnitz.de,” ZPS asked for valuable information, including names, addresses, and employers in exchange for cash rewards of between €30 and €120.

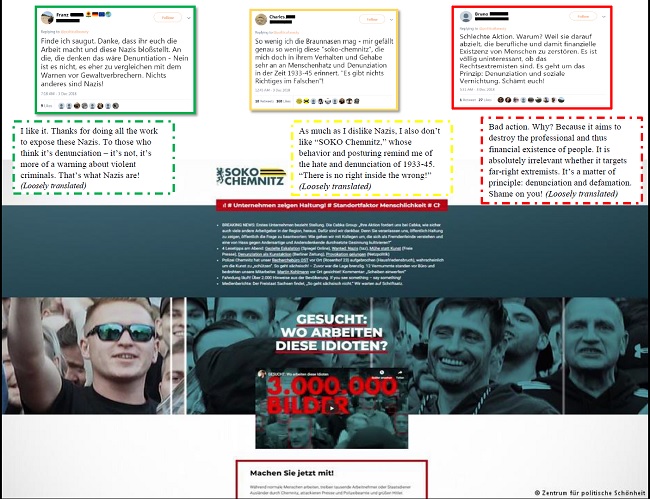

SOKO Chemnitz went viral within hours, causing a variety of controversial reactions on social media. Some people endorsed the initiative, expressing thanks that someone finally revolted and showed moral courage. Those same people thought that police investigations had neglected far-right political crimes like the alleged National Socialist Underground’s (NSU) series of attacks against migrants living in Germany, but heavily prosecuted left-wing activities such as the G20 protests in Hamburg. Others supported the gist of the campaign but condemned the technique of public denunciation as being too reminiscent of the type of hate and defamation that took place during the Nazi regime and later during Stasi control in Eastern Germany, believing that those types of campaigns—whether on the left or right—never belong in a democratic constitutional state like Germany. A large number of people harshly criticized SOKO Chemnitz, expressing shame that someone could even conceive of taking such actions in present day Germany, while a few individuals also demanded that the initiators of the intimidation and defamation campaign face legal consequences.

Compiled controversial reactions on Twitter after launching “SOKO Chemnitz” online (12/03/2018)

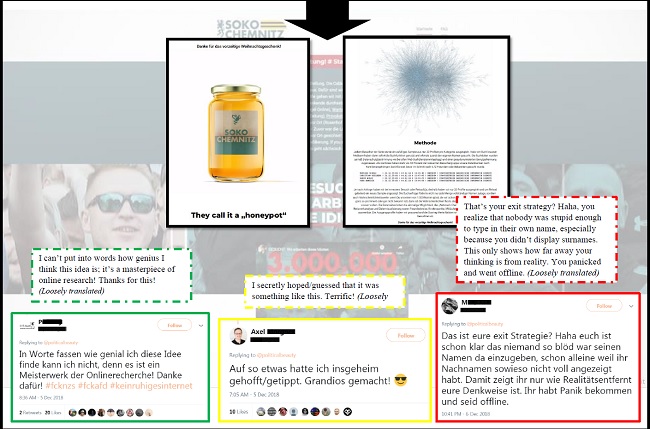

On December 5, 2018, ZPS deactivated its database and revealed the true intention of SOKO Chemnitz, calling it a “honeypot trap.” ZPS used the website SOKO Chemnitz to lure far-right sympathizers and neo-Nazis into revealing their identities and surrendering the identity of their networks.

ZPS assumed that people who participated in the Chemnitz riots would want to check if their picture was uploaded. But the website only showed a maximum of 20 pictures at once, thereby inducing the user to type first and family names into the search function, instead of manually scrolling through numerous samples. By collecting those search terms, ZPS created a list of so-called “braune Mobber” (Nazi rioters). Using analysis and visualization tools, the group then evaluated connections between central figures, influencers, followers, and physical whereabouts. The website eventually posted this statement: “[u]sing the search function, you [Nazis] shared more with us than publicly available sources could ever have revealed.”

After announcing the hoax, reactions on social media were again controversial. The majority of people who responded were amused and congratulated ZPS on this “awesome campaign” and its “huge success.” Those previously shocked by the call for a denunciation campaign expressed relief, claiming that they suspected all along that the campaign served a deeper and more useful purpose. Some people mocked neo-Nazis and Saxony’s police for falling for the trap. Others challenged the validity of the results, either doubting that Nazi rioters “were stupid enough to search their names” or wondering whether ZPS possessed the technological expertise necessary to carry out its plan. They believed the results to be fabricated and suspected that ZPS panicked in response to the backlash against the campaign and used the honeypot explanation to save face.

Compiled controversial reactions on Twitter after revealing the “honeypot trap” (12/05/2018)

Much remains unknown. Despite publishing a small sample of its search activity records and an unreadable network analysis diagram, ZPS has yet to present its findings to the public. However, on December 12, 2018, ZPS announced on its website that it submitted all relevant data—including names, IP-addresses, search requests, and automatic term weighting—to the police of Saxony, Germany’s interior ministry, and the criminal police office’s specialized unit on countering militant far-right extremism in Berlin. ZPS also said it had deleted its own database and referred further questions to those authorities.

Did ZPS just put a cherry on the cake—or was their logic flawed and overly simplified from the beginning? A skeptic might classify the data as irrelevant or non-incriminating, given that not every Chemnitz protestor was a neo-Nazi, glorified Hitler and the Third Reich, or committed violent crimes. On the other hand, the data might have revealed important information on far-right networks in Eastern Germany and could therefore help intelligence agencies to monitor groups and individuals, analyze trends, and potentially dismantle violent circles. Whether SOKO Chemnitz revelations bear fruit in the future remains an open question, one that may never be answered definitively.

Extremists: Their Words. Their Actions.

Fact:

On April 3, 2017, the day Vladimir Putin was due to visit the city, a suicide bombing was carried out in the St. Petersburg metro, killing 15 people and injuring 64. An al-Qaeda affiliate, Imam Shamil Battalion, claimed responsibility.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.