Executive Summary

This paper documents and analyzes the challenges of delivering humanitarian assistance to Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen. It outlines how the Houthi regime has established an organization dedicated to controlling and diverting assistance, while many of the agencies providing humanitarian aid do not seem to have implemented adequate guardrails or oversight to ensure the resources reach their intended recipients and are not diverted by the regime.

The total amount of aid poured into Yemen over the past decade exceeds $20 billion, and it is estimated that approximately three-quarters of aid flows to Houthi-controlled areas. This assistance takes a variety of forms, from infrastructure projects to training workshops, but most of the funds are allocated to unconditional resource transfers—programs designed to provide cash and other essentials to Yemenis facing dire conditions.

The Houthi regime has built an elaborate system and structures designed to ensure that the resources are allocated toward their regime’s needs rather than Yemen’s neediest. The Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA) is the Houthi organization tasked with this responsibility, and it is run by one of the regime’s most powerful figures and longtime Houthi loyalist, Ahmed Hamid. Through SCMCHA, the regime oversees and controls every aspect of humanitarian work in their territory: determining beneficiary lists, providing permits for any movements of aid organizations’ personnel, and deciding which local entities are eligible to serve as contractors, local implementation partners, or third-party monitors for humanitarian projects. The Houthi regime has also used its leverage over aid agencies to advance its economic war of attrition against the Government of Yemen, worsening the crushing poverty that afflicts all areas of the country.

While operating in these challenging conditions, many aid organizations appear to minimize or ignore altogether the challenge of their relationship with the Houthis. In general, they appear to emphasize the metric of how much aid was brought into Yemen, while diminishing the metric of whether those in need of assistance received it. This leads to suboptimal outcomes. In one of the instances documented in this report, aid diversion rates for an entire governorate appear to be around 80 percent. The lack of transparency and accountability among the United Nations (UN) and the community of international non-governmental organizations (INGO) operating in Yemen regarding aid diversion raises serious doubts about the effectiveness of their efforts. Yemenis might be better served by major overhauls to the operating procedures of these organizations. This would ensure a more effective delivery of humanitarian aid while minimizing the benefits the Houthi regime can extract from these operations.

Assistance Overview: The Yemeni Context

Background

According to a 2024 report released by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA),* the number of “people in need” in Yemen has vacillated between 20.7 million to 24.1 million from 2019 to 2023. During that time, annual sums ranging between $3.64 billion in 2019 to $1.7 billion in 2023 have been invested in alleviating Yemen’s crushing poverty—which has long been severe, but which has been significantly exacerbated over the past decade by the civil war. For the current year, 2024, OCHA is seeking $2.7 billion in commitments to support humanitarian operations in Yemen. Given the sums of money at stake and the complexity of the Yemeni landscape, it is worth examining closely how these funds are being spent or invested.

It is important to emphasize that the aim of this research is not to deny the tragedy of the war affecting Yemen or the dire needs of its people. The aim of this work is to highlight the ways in which much-needed aid is vulnerable to diversion or abuse by the Houthi regime for its benefit, often at the expense of those in need. Of course, some level of aid diversion may be inevitable in war-torn countries, particularly in regions under the control of extremist and terrorist groups. However, given the scope of the aid to Yemen, which is in the billions of dollars each year, the evident lack of transparency surrounding this issue should cause especially serious concern.

Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen likely receive the majority of resources intended to alleviate the country’s humanitarian crisis. This is not surprising since Houthi-controlled areas contain the vast majority, approximately 70 to 80 percent, of Yemen’s 31 million residents.* The population statistics are proportionate with statements regarding the World Food Programme (WFP) activities in Yemen:

In 2022, the WFP estimated that its general food assistance (GFA) program was helping upwards of 13.2 million people.*

When WFP suspended the GFA in Houthi-controlled areas,* a joint statement from 22 international non-government organizations (INGOs) active in Yemen included an estimate that this step would “impact 9.5 million people experiencing food insecurity across northern Yemen.”*

From this, one could extrapolate that about three-quarters of those supported by the GFA budget are likely located in Houthi-controlled areas.

The example provided is not an outlier as WFP has the highest budget* of the UN/INGO organizations operating in Yemen, and GFA represents “the largest activity implemented by WFP in Yemen.”* Presuming that the prices of the relevant commodities are comparable in northern and southern Yemen,* at least in terms of dollar amounts if not in terms of local currency,* it is highly likely that this 75 percent and 25 percent proportion is roughly representative of how the aid budget is allocated in Yemen more broadly.

Based on a rough and conservative estimate that the humanitarian assistance budget for Yemen is around $2 billion per year, it is reasonable to assume that around $1.5 billion worth of aid is directed toward Houthi-controlled areas. This is a considerable amount, especially since the vast majority of the assitance, at least from the WFP, arrives in the form of unconditional resource transfers.* In a country with a GDP per capita of around $700 and few sources of revenue, it should not be underestimated how signifcant this inflow of over $1 billion of assitance into Houthi territory is to both the local economy and the Houthi regime. Given the $4 billion in total estiamted Houthi revenues* (2020), tens or hundreds of milions of dollars skimmed off foreign assitance could amount to a substantial percentage of the Houthis' eocnomic resources—whether such funds are formally accounted for within the Houthi-controlled Snaa government's official budgeting process or not.

Houthi Interference in Humanitarian Aid

The Houthi organization officially responsible for coordinating humanitarian assistance is the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA). SCMCHA was established in 2019 to replace its predecessor organization, National Authority for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Recovery (NAMCHA). Although the organization’s senior leadership did not change, the new reincarnation took on an even more aggressive and predatory approach toward humanitarian assistance organizations.* Both NAMCHA and SCMCHA have been run by Chairman Ahmed Hamid,* who is believed to be “possibly the most powerful Houthi civilian leader not bearing the name al-Houthi.”* Hamid, known by the kunya “Abu Mahfouz,” also serves as Director of the Office of Houthi President* Mahdi al-Mashat, leading some in Yemen to joke that Hamid is so powerful his title ought to be “the president of the president.”* He rose through the ranks because he is a longtime devotee of the late founder of the movement, Hussein al-Houthi, as well as a trusted associate of Hussein’s brother and successor Abdul-Malik al-Houthi.

Left: Ahmed Hamid*,

Right: SCMCHA’s insignia*

The fact that such an important regime official heads SCMCHA points to the weight and sensitivity of its work. In some sense, the leadership of SCMCHA is a prize, perhaps even a sinecure, since this post oversees a sector of considerable size —arguably one of the largest and most important sectors—of the economy of Houthi-controlled northern Yemen. The significance of this role within the Houthi hierarchy and the personal opportunities for accruing power and wealth that it presents are hard to overstate. At the same time, it seems clear that SCMCHA’s leader must be competent enough to avoid taking steps that force the humanitarian organizations to end operations in areas under Houthi control and cut off a vital flow of resources.

Since around 2022, Hamid seems to have moved to a more behind-the-scenes role, as he is no longer featured in SCMCHA news updates or mentioned in Houthi-run newspaper articles about humanitarian projects in northern Yemen. It is also possible, though unlikely, that Hamid has been quietly removed from his position. Given Hamid’s centrality to the regime and his proximity to Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, his removal from an integral and potentially lucrative position would likely have sent shockwaves throughout the Houthi movement that would be difficult to keep from the public. Power struggles, or at the very least rumors, would have ensued if someone of Hamid’s stature had been ousted. In addition, if Hamid were dismissed, one might have expected to see a new figure serving as SCMCHA’s Chairman of the Board. Yet, developments indicating Hamid’s removal or replacement have not occurred at the time of writing this report. Still, it is notable that Houthi news outlets have not mentioned SCMCHA’s Board of Directors and Hamid’s role as its Chairman for several years. In addition, Ibrahim “Abu Yahya” al-Hamli has taken on the role of SCMCHA’s Secretary-General rather than Chairman, which requires him to participate in ceremonial affairs as the organization’s senior representative.

Unsurprisingly, it has proven difficult for the Houthis to balance efforts to keep the assistance flowing while also diverting part of the incoming humanitarian aid for their own purposes. For example, in 2019, Ahmed Hamid sought to levy a 2 percent tax on all humanitarian assistance to Houthi-controlled areas.* When questioned about this, the head of the International Organizations Department in the Houthi Supreme Political Council, Qassem al-Houthi, claimed that these funds were necessary to support SCMCHA’s significant operating expenses, saying “[SCMCHA’s work] carries heavy financial burden. It’s in charge of facilitating, distributing, security, and organizing the work of the agencies.”* He then went on to argue that UN agencies spend a much larger percentage of their budget than SCMCHA on overhead, and they do so without oversight.* Regardless, the international community did not find al-Houthi’s argument compelling and SCMCHA’s attempt to tax aid elicited significant and sustained pushback and even led to a public spat between Hamid and another senior regime official known as Mohamed Ali al-Houthi. Eventually, Hamid backed down from his proposed tax on humanitarian assistance.*

In other instances, even the most brazen of SCMCHA’s diversion schemes appear to succeed for some time until they are exposed. For example, in 2020, the Associated Press (AP) reported:

For a time, three U.N. agencies were each giving salaries to [SCMCHA]’s president, his deputy and general managers. Each of the officials received a total of $10,000 a month from the agencies, the spreadsheet shows. The U.N. refugee agency also gave SCMCHA $1 million every three months for office rental and administrative costs, while the U.N. migration agency gave the office another $200,000 for furniture and fiber optics. U.N. officials said [then-U.N. Resident Coordinator Lisa] Grande was “genuinely shocked when she learned about the arrangements.” “She had no idea about the scale of it,” said one senior U.N. official. “Her reaction after that was, we have to fix the situation.”*

This is just one example of SCMCHA being paid to allow humanitarian organizations to help Yemenis. As this report will highlight, diversion of humanitarian assistance budgets to Houthi officials and organizations is an ongoing problem about which aid organizations do not seem to be sufficiently transparent.

Yet, as Yemeni think tank Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies notes of SCMCHA, “not even a simple project can be carried out in northern Yemen without the consent and supervision of [SCMCHA ].”* According to a job posting for the role of Liaison Consultant at UNICEF, “all road access and landing permits for movement of trucks and receiving of aircrafts carrying UNICEF humanitarian supplies must be approved in advance by SCMCHA.”* SCMCHA determines which projects can be undertaken and which local contractors are permitted to conduct business with the UN/INGOs (given that such contractors must be selected from a pool of companies registered and approved by SCMCHA), and it oversees the execution of any and all such projects.*

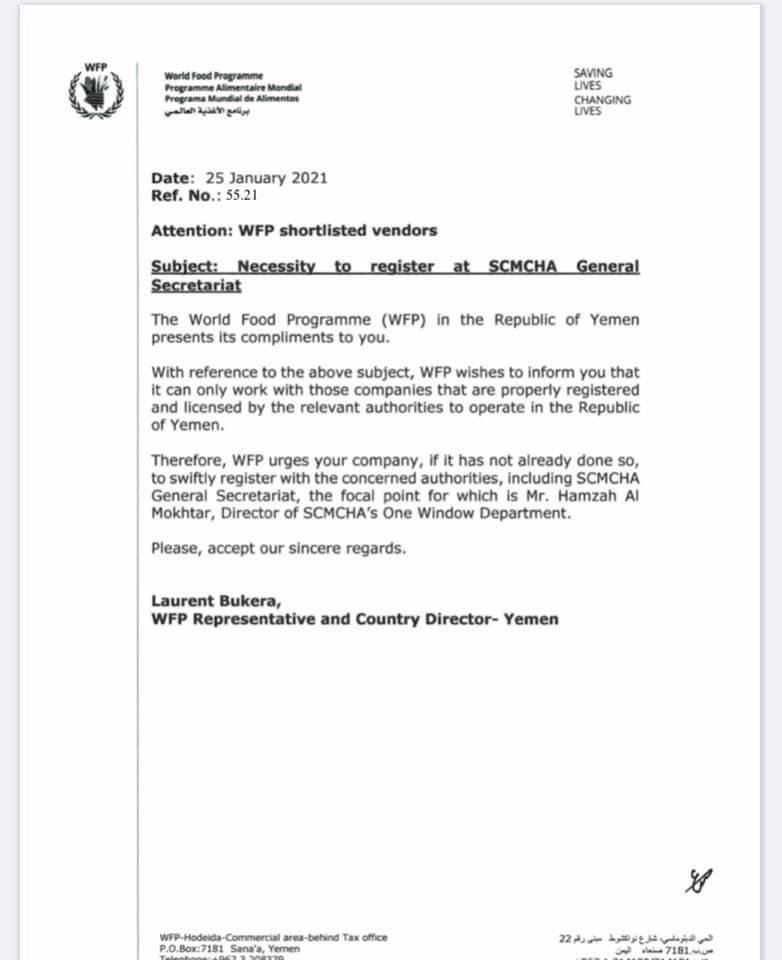

A UNICEF report from 2021 states, “[SCMCHA] continued to require UN/INGO organizations to exclusively contract vendors registered with SCMCHA, limiting the sourcing and competitive selection of vendors in northern Yemen.”* Despite any concerns regarding this practice, major humanitarian organizations do not appear to have resisted. In a tender published in October 2022, UNICEF adopted Houthi criteria by mandating that “Bidders must attach all legal and registration documents including the registration in the SCMCHA.”* In another document roughly equivalent to a Request for Information (RFI) published by the WFP in August 2023, the prerequisites to participate include a “license from SCMCHA to manage contracts with UN agencies (if the supplier is working in the north).”* It is particularly noteworthy that the latter document is part of WFP’s search for local contractors, vetted by SCMCHA, to run spot checks and audits on the distribution of humanitarian assistance in order to prevent aid diversion by SCMCHA and other Houthi affiliates.

Left: A Tweet highlighting the head of the Bonyan Foundation Mohammed al-Madani and his strong familial ties to the Houthi regime: [Translation from Arabic to English] “Major General Abdul-Hakim Hashem Al-Khaiwani, Head of the Security and Intelligence Service, sent a message of condolences and consolation to the Commander of the Fifth Military Region, Major General Yousef Al-Madani, the Chairman of the Supreme Agricultural and Fisheries Committee, Ibrahim Al-Madani, and the Executive Director of the Bonyan Foundation, Dr. Muhammad Al-Madani, on the death of their brother Yahya Al-Madani.”*

Right: A document from the WFP requiring vendors to register with SCMCHA.*

Given Yemen’s challenging operating environment, similar to other conflict zones, much of the on-the-ground humanitarian work is subcontracted out to local partners. As previously mentioned, this allows for the Houthis to control which local organizations are eligible to execute such projects and how they do so. At times, the Houthis go beyond simply determining general eligibility and seek to pressure aid organizations to work with specific, Houthi-preferred local subcontractors. According to a PBS News report, “Several humanitarian workers said the Houthis are also trying to force the U.N. to work with NGOs they favor, particularly an organization known as Bonyan, which is filled with Houthi affiliates… Houthi leaders stopped the U.N. agencies from delivering food in Yemen’s Hodeida province, unless they used Bonyan for the distribution.”*

Based on several other reports and documents, there is good reason to suspect that Bonyan is not a neutral humanitarian organization focused on alleviating human suffering. Bonyan holds events on behalf of the Houthi regime, including ceremonies for the families of Houthi “martyrs,”* and Bonyan’s international relations office is based in Iran.* Abdul-Karim Hassan al-Matari, who manages Bonyan’s international relations, is also located in Iran and appears to have made numerous public appearances with Houthi Ambassador to Tehran Ibrahim al-Dailami.* The Houthi’s Bonyan Foundation and an Iranian organization known as Owais Qarani have signed a strategic partnership agreement: According to Owais Qarani’s website, it serves as the only “approved” conduit for collecting and sending funds from Iran to the Houthis.* While the latter organization’s English name is “Owais Qarani voluntary group for humanitarian aids,” the Persian name of the organization translates to “The Owais Qarani Jihad Group.” According to its website, Owais Qarani is engaged in providing aid to the families of Houthi “martyrs” and it even held joint events with the Houthis commemorating the late IRGC-QF Chief Qassem Soleimani.*

The logo of the Iran-based and Yemen-focused Owais Qarani “charity organization” which has very different names in English and Persian. *

The Bonyan Development Foundation appears to have generated enough business to create a subsidiary—Bonyan Academy—and expand into a new realm. It cannot be ruled out that Bonyan Academy, or the training courses it provides, are funded by international aid organizations. A 2019 UNICEF report identifies Bonyan Academy as an option for those seeking technical or vocational courses* and the Bonyan Academy frequently cites its organizational focus on “sustainable development” on its website—not a previously recognized core tenet of the Houthi ideology.*

However, SCMCHA not only controls the approval and execution of the projects, it also tightly regulates the behavior of humanitarian personnel in Yemen. ETC Yemen, an organization funded primarily by the WFP and dedicated to providing “telecommunication services to the humanitarian community responding to the crisis” noted in January 2021:

The Supreme Council for Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and International Cooperation (SCMCHA) banned UN and NGO staff from organizing or participating in any type of online/virtual studies, workshops, monitoring and other activities without pre-approval from SCMCHA.*

This new Houthi regulation was obviously intended to reduce transparency and avoid the disclosure of information that could disrupt SCMCHA’s interference in humanitarian groups’ operations. Nevertheless, in September 2022, ETC Yemen announced that it “completed setting up the ICT infrastructure in the office of the Supreme Council for the Management and Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (SCMCHA) in Sana’a.” * ETC Yemen appears to be providing (free of charge) the very same products and services to SCMCHA that the regime is denying their humanitarian colleagues the right to use freely.

With a Houthi official as powerful as Ahmed Hamid serving as Chairman of the Board, it is to be expected that SCMCHA’s board is stacked with some of the most senior and powerful officials in Houthi-controlled Yemen. This includes two top security officials, Interior Minister Abdul-Karim al-Houthi and Chief of the Security and Intelligence Service (SIS) Abdul-Hakim al-Khaiwani. The SIS serves under the Houthi Ministry of Interior (MOI), and the former has a broad range of responsibilities that include but are not limited to covert activities on both sides of the Houthis’ front lines.

Minister of Interior Abdul-Karim al-Houthi (left) and SIS Chief Abdul-Hakim al-Khaiwani (right) appear in a June 2024 video “exposing” what the Houthis called a “U.S.-Israeli spy ring” including numerous humanitarian aid workers.*

SIS is the security organization that unofficially “monitors” humanitarian assistance in Yemen—serving as the intelligence and enforcement arm of SCMCHA. SIS Chief Abdul-Hakim al-Khaiwani and several other SIS officials, including Abdul-Qader al-Shami and Mutlaq al-Marrani, have been sanctioned by the U.S. under the Global Magnitsky Act for their roles in human rights violations. According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s announcement in 2020, “al-Marrani played a significant role in the arrest, detention, and ill treatment of humanitarian workers and other authorities working on humanitarian assistance and was also found to have abused his authority and influence over humanitarian access as leverage to generate personal profit.”* Yemeni activist Samia al-Houry noted in 2020 that al-Marrani was involved in “recruiting girls to spy on the activities of international organizations and United Nations employees.”* Despite being sanctioned by the U.S. in 2020 for malign activities, including targeting of aid workers in Yemen, al-Marrani apparently has continued to meet with humanitarian organizations as recently as 2022.*

In October 2023, it was reported that SIS detained and then murdered Hisham al-Hakimi, who worked for Save the Children International;* it remains unclear precisely why the SIS detained, tortured, interrogated, and then murdered this aid worker, but Yemeni human rights organization Mayyun claims that SIS Undersecretary Mohammed al-Washli oversaw the “investigation.”* Unfortunately, the Houthis have not suffered consequences commensurate with the severity of this attack on humanitarian assistance personnel. After al-Hakimi’s death, Save the Children released a mildly worded and vague condemnation of al-Hakimi’s death that did not mention the Houthis by name,* which was followed by only a brief suspension of operations in Houthi-controlled areas.*

Khabar News Agency also alleges al-Washli oversaw the forced disappearance of two elderly educators, Sabri al-Hakimi and Mujib al-Mikhlafi, who have been held by SIS since October 2023. The pair are reportedly accused of providing information for reports that accuse “the Houthis of committing a number of violations related to children in Yemen,” presumably in the realm of indoctrination and recruitment of child soldiers.* According to a Yemeni Government official, during the single visit allowed to the detainees since their disappearance, visitors identified signs of torture on the detainees’ bodies.*

Left: In 2014, SIS Undersecretary Mohammed al-Washli made several appearances on al-Masirah TV.

Right: Encircled on the right side of the picture is the individual suspected to be Hamid al-Ansi. He is seen giving a “thumbs up” at a Berghof Foundation event on inclusive governance.

Another example of SIS penetration of international aid programs is evident in the Houthi-controlled Dhammar governorate of Yemen. The Deputy Director of SIS in Dhammar, Hamid al-Ansi,* is involved in a $460,000 water project in the governorate funded by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and serves as the “head of the conflict resolution team” for the project. It is conceivable that the project’s delay due to an undisclosed conflict was the result of the Houthi regime, through al-Ansi’s influence, seeking to impose demands (whether for personal gain or regime interests) on the humanitarian organizations involved in the project as a condition for it to resume.* Ironically, it would appear that this same SIS official also participated in the Berghof Foundation’s “inclusive governance” workshop. It is unclear if Berghof was aware of the participation of senior Houthi intelligence figures in the event. *

Given the activities of SCMCHA (and SIS), which target humanitarian organizations, it is not surprising that Yemen expert Afrah Nasser concluded that “SCMCHA’s main purpose is to deliver intelligence to senior Houthi officials about independent local humanitarian aid groups, to impose hundreds of restrictions on local and international aid organizations, and to tax or otherwise deduct money from international humanitarian aid funding.” * When one international humanitarian official uncovered that his Yemeni employees were spying on him for the Houthis, his complaint on the matter resulted in the revocation of his visa and his expulsion from the country.* Rather than helping to orchestrate or facilitate humanitarian aid, SCMCHA appears to pose the primary obstacle to its effective delivery—delaying projects, diverting resources, and targeting humanitarian personnel.

Even once the SCMCHA hurdle has been cleared, aid groups still find themselves subjected to further Houthi efforts to divert their resources. A leaked official document from March 2022, showed Houthi Minister of Health Taha al-Mutawakkil demanding $1 million from the World Health Organization (WHO) for purchase of medical supplies. London-based Arabic newspaper al-Sharq al-Awsat, which published al-Mutawakkil’s memo, noted concerns among Yemeni health sector workers about the Houthi minister’s double-dealing. These sources alleged that al-Mutawakkil’s family runs several businesses to which it tries to direct WHO resources, including multiple private hospitals, pharmacies, and companies with exclusive deals for import of pharmaceuticals.*

At almost every step, aid groups operating in Yemen are forced to make both direct and indirect payments to the Houthis. For example, Yemeni media report that aid groups and visiting foreign delegations must rent armored cars from one of two companies, “Golden Car” and “Happy Journeys,” both of which are owned by relatives of senior Houthi leaders. In addition, reports indicate various other forms of opaque fees that must be paid for Houthi government “approvals” for projects, approvals that often cost thousands of dollars in filing fees.* In addition to the enrichment opportunities these schemes provide, these “regulations” also give the Houthis greater ability to monitor, control, and restrict aid groups’ activities at each step of the way.

It is also important to note that the Houthis use their leverage over humanitarian organizations to advance their economic warfare against the internationally recognized government (IRG) of Yemen by diverting economic activity away from areas under the latter’s control. For example, in 2023, an Aden-based bank alleged that it was disqualified from serving as a channel for emergency cash transfer aid for a UN-funded INGO because the Houthis issued a directive that international organizations not engage with banks that their regime has not authorized.* Another example of this is SCMCHA’s imposition of a $200 tax (more than a quarter of the GDP per capita in Yemen) on any humanitarian shipment moving over land from IRG-controlled areas to Houthi territory.* The apparent logic behind this levy is a Houthi effort to control the flow of imports* by creating an economic incentive to use the Houthi-controlled ports of Hodeida, Ras Isa, and Salif in order to avoid the tax.

Aid agencies are presumably aware of the Houthi efforts to divert and distort their assistance and should maintain distance from the regime to preserve an effective and neutral humanitarian response, though they do not appear to have always done so. For example, in late 2022, UNHCR published a request for quotation (RFQ) for “the Supplying, Installation, Implementation and Testing for Server Room and ICT Equipment.”* The intended recipient of this procurement effort was evident as the point of delivery and construction is listed as the SCMCHA building in Sanaa. If the UNHCR were providing these supplies to SCMCHA in exchange for access to Houthi-controlled areas or for any other purpose, it would likely violate the same Code of Conduct the UN required its own suppliers to abide by.* In another example, a Yemen-based NGO known as Haidara Foundation for Peace and Human Development (which receives funding from U.S.-based organizations such as the United Humanitarian Foundation or UHF*) appears to have especially close ties to the Houthi regime. Haidara honored the Houthi Governor of Hodeida Mohammed Ayash Qahim and presented him with an award,* and Haidara’s aid projects are often described as “overseen by SCMCHA, funded by UHF, and implemented by Haidara.”* At the inauguration of one such UHF-funded and Haidara-implemented project , SCMCHA’s Secretary-General Ibrahim al-Hamli unveiled a plaque noting that the event was “on the occasion of the eighth anniversary of national steadfastness against [the Saudi-led coalition’s] aggression” and displaying the logos of SCMCHA, Haidara, and UHF side by side.*

Aid agencies are presumably aware of the Houthi efforts to divert and distort their assistance and should maintain distance from the regime to preserve an effective and neutral humanitarian response, though they do not appear to have always done so.

Left: Houthi Governor of Hodeida Mohammed Ayash Qahim (second from right) receiving an award from Haidara.*

Right: SCMCHA Secretary-General Ibrahim al-Hamli unveils a plaque celebrating an aid project funded by UHF and implemented by Haidara.*

In light of the lack of effective pushback to much of the Houthis’ problematic behavior, many Yemenis and those involved in aid work in Yemen often view the humanitarian effort as unhelpful. According to Sarah Vuylsteke’s report “When Aid Goes Awry”:

In addition to perceiving the response as unprincipled, [Yemenis] described it as corrupt, out for personal or institutional gain, of poor quality, inappropriate and generally failing to understand Yemen and its needs. Non-Yemeni aid workers, to a large extent, shared similar opinions, rating the Yemen response as among the worst and least effective responses in which they had worked.*

The following section will consider the framework for understanding how such a well-resourced humanitarian effort failed to meet the needs of impoverished Yemenis.

Data Collection, Aid Distribution, and Minimal Transparency

This section addresses the structural problems in how aid programs operate in Yemen. First, it will assess severe deficiencies in collecting relevant data to determine who is in need of aid. Second, it will examine significant shortcomings in how aid is distributed to the targeted recipients based on the above data. Finally, it will consider how aid organizations’ activities are presented, or misrepresented, to the public.

One of the most critical elements of any aid program is assessing who is most in need of assistance to ensure that the resources available are allocated most effectively. It is critical for the aid organizations to accurately determine which residents need assistance, what type, and how much support they require. Unfortunately, significant components of the data collected to understand the humanitarian situation in the Houthi-controlled areas of Yemen are prone to manipulation by the Houthis.

In their 2020 report entitled “Deadly Consequences,”* Human Rights Watch (HRW) noted that “Almost all aid groups interviewed said the Houthis regularly tried to control the ‘beneficiary lists,’ the names appearing on aid recipient lists.” The report goes on to cite aid workers interviewed for the project who noted that the beneficiary list for assistance is provided by the Houthis* and “aid agencies are then supposed to verify it but that rarely happens.” This may not be surprising as, according to another aid worker cited in the HRW report, “it is very hard to independently verify the identity of those on the [Houthi-provided] list and negotiate changes.”

A separate report published the following year by HERE-Geneva and the European Commission, quoted a UN employee involved in the assessment as saying, “[the UN] wanted to target those most in need, and then of course [Houthi authorities] don’t like it: because sometimes we have an obligation to update beneficiary lists, and they object to that. When you think about it, it’s a very basic thing actually.”* The report assessed that Houthi interference in allocation of international assistance was so pervasive that it “was the single most mentioned example [of impediments to effective delivery of aid] by all respondents.”

The information from these two reports comports with a third assessment, conducted by the NGOs Mwatana and Global Rights Compliance (GRC). The third paper identified Houthi use of humanitarian aid as an improvised form of life insurance for their fighters, by adding families of Houthi soldiers who were killed in action to the beneficiary lists.* It is easy to see how these activities could cross-contaminate in Houthi-run Yemen, as organizations like SCMCHA have a great deal of leverage over humanitarian aid organizations but also undertake public events to support the families of “martyrs.”* This aligns with what some aid workers and diplomats claimed in 2019, as reported by CNN, that most of the diverted aid was used to buy political support on the international community’s dime.*

Of course, Houthi control over humanitarian assistance is not only used to bestow favor but can also be used to punish. The Houthis have reportedly removed from beneficiary lists those viewed as inadequately loyal to the regime, regardless of their needs.* A 2022 UN report cited numerous cases in which the provision of aid to a family was dependent on whether they sent their children to fight for the Houthis or whether their relative, a schoolteacher, taught the extremist Houthi curriculum in the classroom. * That same year, the Houthis signed on to an Action Plan that “commits the authorities and their forces to comply with the prohibition of the recruitment and use of all children in armed conflict, including in support roles.”* Unfortunately, there is well-documented evidence that since then, the Houthis have not abided by their commitment and have continued recruiting children as young as 13 to fight in their military.*

Of course, Houthi control over humanitarian assistance is not only used to bestow favor but can also be used to punish. The Houthis have reportedly removed from beneficiary lists those viewed as inadequately loyal to the regime, regardless of their needs.

When humanitarian organizations do not adhere to beneficiary lists provided by SCMHCA, either by seeking to provide to those the Houthis deem ineligible or refusing to re-direct aid to those the regime favors, such aid programs are then suspended or paralyzed in Houthi-controlled areas. In one case cited by the UN, an organization’s refusal to operate in accordance with Houthi directives resulted in 90 percent of its movement permits being denied by SCMCHA.* Likewise, the report by Mwatana and GRC cited at least two cases in which refusal to abide by Houthi-sourced beneficiary lists resulted in the suspension of cash transfer and vocational training programs.

Interference in the list of approved beneficiaries aside, much diversion can (and does) occur during the storage and delivery process. For example, in January 2020, the WFP disclosed a massive theft of humanitarian assistance, though they did so without calling out the Houthis by name. In a Tweet following the events, WFP wrote, “an armed group stormed a World Food Program warehouse in Hajjah Governorate and took 127.5 tons of food aid.”* A similar occurrence took place in November 2020, when the Houthis forcefully seized upwards of 300 aid containers under the pretense that they were expired.* However, these types of events are the exception rather than the rule; the vast majority of the Houthis’ diversion of aid does not involve armed robbery and therefore does not elicit this kind of publicity.

While the armed seizure of 127.5 tons of WFP aid garnered headlines in 2020, CNN reported that Houthis are estimated to have quietly diverted ten times that amount of food over the course of two months in Sanaa alone in 2018.* Major UN/INGO programs hire numerous local subcontractors to deliver humanitarian assistance in many different governorates, with hundreds of distribution points in each governorate. To ensure the efforts are effective, programs often hire implementation partners (IPs) to deliver and third-party monitors (TPMs) to oversee delivery and alert the UN/INGO to any problematic practices. As mentioned, in order to work with international aid organizations in northern Yemen, both types of local partners must be approved by the Houthis.

It is difficult to describe with any specificity exactly how aid is physically diverted or where it goes. Nevertheless, there are strong indicators that diversion of aid supplies is indeed taking place on a large scale. In many instances, those identified by humanitarian organizations as requiring assistance and to whom it has ostensibly been allocated and dispatched do not receive it. For example, according to an AP report, only one-third of the intended beneficiaries received aid in the Houthi stronghold of Saada.* The AP report provides a sense of the scale of diversion, as it notes that the UN sent enough food to feed nearly 1 million people for two months, although they allegedly had determined that only about half that many were in need. Yet, after around 80 percent of the supplies were evidently diverted, only around 150,000 people in need received assistance.* In light of what appears to be a massive diversion rate, it should come as no surprise that the UN reported that “In places like Saadah, the Panel was informed that there is direct involvement with SCMCHA on distributions […] This includes staff selections for humanitarian organizations and interference in local NGO partners who distribute assistance.”* Similarly, according to a CNN report,* more than half of the intended aid recipients in many districts of Sanaa did not receive any of the aid allocated for them.* The problems of diversion by the IPs as well as UN/INGO collaboration with the regime is corroborated by statements from a senior defector from the Houthi regime. Former Houthi official Abdullah al-Hamidi noted that at least 15,000 food baskets provided to Sanaa’s Ministry of Education each month by humanitarian aid organizations are “diverted to the black market or used to feed Houthi militiamen serving on the front lines.”*

In a more permissive environment, the implementation of UN/INGO-funded aid programs would be overseen by the organizations sponsoring them to ensure that the IP distributed resources in accordance with their intended purpose. However, given the major restrictions imposed by SCMCHA on the UN/INGOs, the latter has sought to outsource the oversight role to local TPMs, which in turn seem to be largely under the control of the Houthis. The use of TPMs is generally a last resort for aid agencies seeking improved oversight for their assistance efforts,* and in Yemen it has yielded highly problematic results.

A report commissioned by the UN and published in 2022 assesses that “monitoring missions have largely been outsourced to TPMs and to telephone polling companies.”* It has become apparent that the shift to overreliance on TPMs as a means to overcome UN/INGO access challenges has not resolved the challenges of delivering aid in Houthi-controlled areas. According to the report, “Third-party monitoring – the principal mitigation measure put in place – does not seem to have changed this picture.” * Further, the report concludes, the disconnect between the UN/INGOs and the TPMs they have hired “might explain why [the UN/INGOs] commissioning the aid programme have not been able to influence the quality of the implementation, or at least why they might not have known about quality issues.” * Aid agencies have hired external contractors to enhance access and oversight for aid projects, but the TPMs run into the same insurmountable challenges as the organizations themselves.

These various challenges mean that fully transparent documentation of the use of funds in Houthi-controlled areas might not be possible due to limited visibility into the “last mile” of delivery. There seem to be no detailed reports by aid organizations operating in Yemen that provide thorough estimates for the percentage of aid diverted, giving rise to major transparency concerns. As recently as 2023, UNICEF produced an internal audit of its own evaluation and monitoring capabilities nine years into the famine relief effort, concluding that:

Based on the audit performed, [the report] concluded that the assessed governance, risk management or control processes were Partially Satisfactory, meaning they were generally adequate and functioning, but needed improvement. The weaknesses or deficiencies identified were unlikely to have a materially negative impact on the performance of the audited entity, area, activity, or process.*

In an apparent contradiction, however, the report also assesses “[the auditor] found insufficient evidence that implementing partners were distributing supplies to intended beneficiaries at the right time, in the right quantities and of adequate quality.”* It goes on to recommend that UNICEF require its TPMs to fulfill the essential role of obtaining information regarding “the type, volume or value of supplies distributed and to whom.”

The question of who receives which aid is essential when trying to ensure the well-being of Yemen’s neediest, but UNICEF is not the only major organization to minimize its significance while shifting the focus of self-assessments to the quantity of aid delivered. In 2020, the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) launched a £ 250 million multi-year Food Security Safety Net Programme for Yemen to fund humanitarian organizations in in the country* and has since encountered similar problems. Two years into the project, the TPM determined that it ought not even try to assess the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems of the FCDO’s partner organizations* in Yemen, noting:

The final M&E assessment revealed significant issues with the partner’s M&E systems, which would make delivery of a standard M&E assessment report of little use to FCDO Yemen and thus poor value for money (VfM).*

In essence, two years into the FCDO project, the M&E systems of its partners had encountered such significant challenges that an assessment was deemed impossible. Yet as of June 2023, the FCDO assessed its overall Food Security Safety Net Programme in Yemen with a series of three grades: A, A+, and B.* The first two grades were for how many people they targeted with their support for cash-based assistance programs, and this had a cumulative impact weighting of 80 percent. The third grade was for whether the aid targeted the right people efficiently and effectively— a seemingly essential metric for success. Despite recording that this project failed to achieve an aid diversion rate of 20 percent or lower and without explaining what the actual diversion rate was, the report nevertheless awarded the project a grade of B for this criterion. However, the metric of efficient and effective targeting of aid was assigned an impact weighting of only 20 percent within the overall grading of the report.

It is also unfortunate that the publicly available budgets of many UN/INGOs do not provide the necessary types of data that would enable external review. For example, UNICEF releases numerous reports each year, none of which enable one to connect the dots: What amounts were paid to whom for which deliverables?

The organization’s Supply Annual Report for 2022 provides budgetary numbers in very generic terms: for what purpose or cause was the money used.*

The Annex for Supply Annual Report then provides specific details on which contractors were used and the amounts they were paid but includes only very generic categories of deliverables.*

The UNICEF contract database provides similar information about how much money was spent for which category of expense but without specifics regarding the contractor and the deliverables or quantity of deliverables.*

The Country Office Annual Report provides country background information and very general numbers on the amount of people who were helped.*

As mentioned, the information UNICEF provides does not include which companies were paid what amount for which deliverables. While allowing the public access to the contracts signed with local and international suppliers and partners might not be feasible in all cases, a centralized and detailed database of the proposals solicited and contracts awarded, similar to large procurement databases like USASPENDING.GOV,* should be considered. The lack of centralized and detailed information about aid groups’ contracting practices makes them more vulnerable to Houthi interference as well as scandals resulting from these practices’ exposure. Transparency is firmly in the aid groups’ interest, even if it may create short-term risks of conflict with Houthis or embarrassing revelations.

Finally, it is worth noting the intentional withholding of the names of IPs from the public is a practice that reduces the level of transparency regarding key elements of aid projects. This is common practice in UNICEF’s online documentation of humanitarian projects, where in some cases the organization notes, “IP not published.”* This is particularly concerning considering previously mentioned reports of the Houthis strong-arming aid organizations to use their preferred partners, like Bonyan. The IP and any potential affiliations to the Houthi regime could determine several key aspects of the project’s implementation: Is the regime profiting from this? Is the regime using this program as a tool to bestow favor or buy loyalty? Will this project cause the aid organization to become identified with the regime?

Conclusion and Recommendations

In 2019, a statement by the UN explained “our greatest challenge does not come from the guns, that are yet to fall silent in this conflict - instead, it is the obstructive and uncooperative role of some of the Houthi leaders in areas under their control.”*

Yet, the prospects of providing an influx of aid to Yemen without empowering the Houthis are slim. The group’s grip over the Yemeni economy is strong and was built up through many years of concerted effort. The Houthi regime is uninterested in facilitating long-term economic development beyond a means to enhance its power, enrich its senior officials, and fund its military. So Abdul-Malik al-Houthi is highly unlikely to agree to or abide by any rules that would make Yemen more inviting to conduct business, train and develop local partners, or provide humanitarian assistance. The reality of the situation in Yemen places the international community in a dilemma with no simple solution: What to do when the regime is holding 20 million people as “hostages” and would opt for their starvation rather than abide by conditions required for the effective distribution of aid to those most in need.

While there is no simple way to determine a practical, ethical, and strategic answer to this question, it is a question that should be acknowledged plainly and openly by the relevant decision-makers. The Houthis are well positioned to skim off a large share of the billions of dollars of humanitarian assistance entering Yemen. Given this exceptionally challenging environment, continued analysis of the Houthi efforts to divert humanitarian aid for their purposes is of crucial importance. The following recommendations are aimed at enabling doing so more effectively going forward:

First, humanitarian organizations should be more transparent about their challenges. It is true that they already occasionally acknowledge the challenges posed by Houthi interference in aid delivery, but usually this consists of a few sentences in the annual report, downplaying the significance of the problem.* Instead, they should present the problem in proportion to its impact on aid efforts (data, delivery, etc.) and also discuss the second order effects on their programming (metrics, oversight, etc.).

When conducting assessments of the humanitarian response, aid organizations should avoid the overwhelming focus on quantity and should focus more on the issue of quality. Claims by humanitarian organizations regarding the impact (quantity) of their response will remain incomplete unless these also include a realistic assessment of the diversion problem (quality).

Second, in future instances of egregious aid diversion to the Houthis, in which either large amounts are skimmed or critical goods/services are provided directly to the regime, governments should consider charging those responsible with supporting terrorism. This now appears to be a more realistic recourse in light of the recent U.S. designation of the Houthis as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) group.*

Third, humanitarian organizations operating in Yemen should be pressed to maintain policies that prevent their projects from being hijacked by the Houthi regime for its political gain. Enabling the Houthis to direct how aid money is used and then publicly claim credit for the projects blurs the boundary necessary for maintaining the integrity of the organizations and the projects they implement. If the longstanding humanitarian principle of neutrality is enforced more rigorously, it will be more evident which, if any, of the organizations have been compromised by the regime.

Fourth, the U.S. and its allies ought to consider developing a counter-strategy for aid diversion. If SCMCHA is devoting a significant amount of time and resources to considering how it can maximize its benefit from the aid entering Yemen, then the UN/INGOs and their supporters should dedicate no less time to developing ideas to minimize Houthi benefits from humanitarian assistance. Until now, the Houthis have shown a clear advantage in outmaneuvering a slow and hulking humanitarian bureaucracy. Aid organizations should develop more robust counter-fraud efforts and internal monitoring and reporting systems. This should include assistance from major donors in developing these dynamic and up-to-date measures.

Fifth, aid organizations operating in Houthi-controlled areas should increase their efforts in sharing promising practices and develop a database of IP and TPM organizations. One model could be the Risk Management Units that the UN has already implemented in several conflict zones, such as Somalia or Afghanistan, to support its humanitarian efforts.

Sixth, a consortium of major donors to aid projects in Yemen could work together to create an independent ombudsperson structure, paid by and accountable to these donors. The power of cooperation between major donors, the independence of these institutions from the chain of command of humanitarian organizations, the leverage derived from donors’ backing to ensure access for investigations, and the setting of universal standards would pose a formidable challenge to systemic efforts by the Houthis or other extremist or terrorist non-state actors that control conflict areas to exploit humanitarian aid.

Finally, major international donors, such as the United States, the European Union, or the United Kingdom, should coordinate efforts to target those Houthi officials and organizations involved in the systematic diversion of aid in Yemen with sanctions. This would not only highlight the issue of aid diversion in Yemen but also ensure that none of the diverted funds can leave Yemen through the international financial system.

While it will undoubtedly prove difficult to push back on the radical Houthi regime, which has shown it places little if any value on the lives of Yemenis, that is certainly the preferable course of action when compared with completely cutting off northern Yemen or simply continuing to submit to the Houthi regime’s blackmail and subsidizing its murderous and tyrannical rule.

TOP

TOP