Fact:

On April 3, 2017, the day Vladimir Putin was due to visit the city, a suicide bombing was carried out in the St. Petersburg metro, killing 15 people and injuring 64. An al-Qaeda affiliate, Imam Shamil Battalion, claimed responsibility.

Abu Khayr al-Masri—born Abdullah Muhammad Rajab Abd al-Rahman—was the U.S.-designated deputy leader of al-Qaeda, sitting directly below Ayman al-Zawahiri. Masri was the son-in-law of Osama bin Laden, having served in the al-Qaeda founder’s inner circle—and as one of his body guards—in the 1990s.“Treasury Designates Seven Al Qaida Associates,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 3, 2005, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js2960.aspx;

Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Martin Chulov, “Al-Nusra Front cuts ties with al-Qaida and renames itself,” Guardian (London), July 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/28/al-qaida-syria-nusra-split-terror-network;

Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Bill Roggio, “Jihadist with same name as Zawahiri’s deputy reported killed,” Long War Journal, July 29, 2011, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2011/07/jihadist_with_same_n.php. Masri was wanted by the U.S. for helping plot the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Thomas Joscelyn, “Senior al Qaeda leaders reportedly released from custody in Iran,” Long War Journal, September 18, 2015, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/09/senior-al-qaeda-leaders-reportedly-released-from-iran.php;

Charles Lister, “Al Qaeda Is About to Establish an Emirate in Northern Syria,” Foreign Policy, May 4, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/04/al-qaeda-is-about-to-establish-an-emirate-in-northern-syria/. Detained in Iran between 2003 and 2015, Masri traveled to Syria following his release to join al-Qaeda there.Martin Chulov, “Al-Nusra Front cuts ties with al-Qaida and renames itself,” Guardian (London), July 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/28/al-qaida-syria-nusra-split-terror-network;

Martin Chulov and Tom McCarthy, “US drone strike in Syria kills top al-Qaida leader, jihadis say,” Guardian (London), February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/us-drone-strike-in-syria-kills-top-al-qaida-leader-jihadis-say. Masri was reportedly killed by a U.S. drone strike in northwest Syria in late February 2017, according to jihadist sources. Following reports of Masri’s death, Baghdad-based terrorism expert Hisham al-Hashimi referred to the al-Qaeda operative as the “ideological leader of the group in Iraq, Syria and Yemen.”Martin Chulov and Tom McCarthy, “US drone strike in Syria kills top al-Qaida leader, jihadis say,” Guardian (London), February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/us-drone-strike-in-syria-kills-top-al-qaida-leader-jihadis-say.

According to an unnamed former al-Qaeda operative, Masri joined Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) group in Egypt in the late 1980s and grew close to Zawahiri himself. The pair reportedly traveled to Sudan and then to Afghanistan during the early 1990s, joining Osama bin Laden’s inner circle. He was implicated in the plotting of the 1998 U.S. Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania, and was reportedly tasked with handling the travel logistics and expenses of al-Qaeda fighters deployed on foreign operations prior to 9/11.Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Holly Fletcher, “Egyptian Islamic Jihad,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 30, 2008, http://www.cfr.org/egypt/egyptian-islamic-jihad/p16376;

Charles Lister, “Al Qaeda Is About to Establish an Emirate in Northern Syria,” Foreign Policy, May 4, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/04/al-qaeda-is-about-to-establish-an-emirate-in-northern-syria/. Masri was also believed to have been a member of al-Qaeda’s management council, overseeing liaison between al-Qaeda and the Taliban.“Al-Qaeda figures or associates linked to Iran,” Washington Post, February 14, 2014, http://apps.washingtonpost.com/g/page/world/al-qaeda-figures-or-associates-linked-to-iran/810/. During this time, according to the Soufan Group, notorious 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed briefed top al-Qaeda leaders on the 9/11 plot in Masri’s residence in Afghanistan.Soufan Group, “A Major Blow for al-Qaeda,” Email, February 27, 2017.

Masri was reportedly arrested in April 2003 by Iranian authorities in Shiraz, Iran.Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Thomas Joscelyn, “Senior al Qaeda leaders reportedly released from custody in Iran,” Long War Journal, September 18, 2015, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/09/senior-al-qaeda-leaders-reportedly-released-from-iran.php;

Charles Lister, “Al Qaeda Is About to Establish an Emirate in Northern Syria,” Foreign Policy, May 4, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/05/04/al-qaeda-is-about-to-establish-an-emirate-in-northern-syria/. According to reports, he was held under house arrest for approximately 12 years before being released in March 2015 in exchange for an Iranian diplomat held in Yemen.Ray Sanchez, Paul Cruickshank, “Syria’s al-Nusra rebrands and cuts ties with al Qaeda,” CNN, August 1, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/28/middleeast/al-nusra-al-qaeda-split/;

Thomas Joscelyn, “Analysis: Al Nusrah Front rebrands itself as Jabhat Fath Al Sham,” Long War Journal, July 28, 2016, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2016/07/analysis-al-nusrah-front-rebrands-itself-as-jabhat-fath-al-sham.php;

Thomas Joscelyn, “Senior al Qaeda leaders reportedly released from custody in Iran,” Long War Journal, September 18, 2015, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2015/09/senior-al-qaeda-leaders-reportedly-released-from-iran.php;

Associated Press, “Iran Eases Grip on Al Qaeda,” Fox News, May 13, 2010, http://www.foxnews.com/world/2010/05/13/iran-eases-grip-al-qaeda.html. Masri traveled to Syria to rejoin jihadist activity, reportedly in support of the Nusra Front.Martin Chulov and Tom McCarthy, “US drone strike in Syria kills top al-Qaida leader, jihadis say,” Guardian (London), February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/us-drone-strike-in-syria-kills-top-al-qaida-leader-jihadis-say. He resurfaced in a July 2016 al-Qaeda audio statement, identified as Zawahiri’s deputy. In the statement, Masri accepted the Nusra Front’s split from al-Qaeda, saying that al-Qaeda would support whatever “protects the jihad of the Syrian people.”Martin Chulov, “Al-Nusra Front cuts ties with al-Qaida and renames itself,” Guardian (London), July 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/28/al-qaida-syria-nusra-split-terror-network;

Martin Chulov and Tom McCarthy, “US drone strike in Syria kills top al-Qaida leader, jihadis say,” Guardian (London), February 27, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/feb/27/us-drone-strike-in-syria-kills-top-al-qaida-leader-jihadis-say.

The United Nations added Masri to its consolidated list of al-Qaeda members on September 29, 2005.“Security Council Committee Adds Seven Individuals To Al-Qaida Section of Consolidated List,” United Nations Security Council, October 3, 2005, http://www.un.org/press/en/2005/sc8516.doc.htm. On October 3, 2005, the U.S. Treasury Department designated Masri for being a member of the former EIJ and al-Qaeda and participating in training and providing material support to al-Qaeda.“Treasury Designates Seven Al Qaida Associates,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 3, 2005, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js2960.aspx.

The United Nations Security Council added “Abd Allah Mohamed Ragab Abdel Rahman” to the al-Qaeda section of its consolidated list.“Security Council Committee Adds Seven Individuals To Al-Qaida Section of Consolidated List,” United Nations Security Council, October 3, 2005, http://www.un.org/press/en/2005/sc8516.doc.htm.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated “Abdullah Muhammad Rajab Abd Al-Rahman” for being a member of EIJ under Executive Order 13224.“Treasury Designates Seven Al Qaida Associates,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 3, 2005, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/js2960.aspx.

Said Nasser al-Teniji is the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood in the United Arab Emirates, or al-Islah.Rori Donaghy, “Muslim Brotherhood review: A tale of UK-UAE relations,” Middle East Eye, December 17, 2015, http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/muslim-brotherhood-review-tale-uk-uae-relations-378120043. The group was formed in 1974 as a non-governmental organization (NGO), and has reportedly sought to impose strict religious laws on Emirati society, particularly on students and women.Lori Plotkin Boghardt, “The Muslim Brotherhood on Trial in the UAE,” Washington Institute, April 12, 2013, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-muslim-brotherhood-on-trial-in-the-uae;

Ali Rashid al-Noaimi, “Setting the Record Straight on Al-Islah in the UAE,” Al-Monitor, October 15, 2012, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2012/al-monitor/uae-setting-the-record-straight.html#;

Ola Salem, “Islah ‘does not represent UAE interests,’” National (Abu Dhabi), October 5, 2012, http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/islah-does-not-represent-uae-interests.

In October of 2012, London’s Guardian published an opinion piece written by Teniji titled The UAE's descent into oppression. In the article, the al-Islah leader sought to bill the group as a progressive organization, and derided the Emirati government for practicing what he referred to as “oppressive” tactics. Teniji further denied government reports saying that detained al-Islah members had admitted to having previously created an armed wing—instead claiming that those individuals had been tortured.“Brotherhood 'sought Islamist state in UAE',” National (Abu Dhabi), September 21, 2012, http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/brotherhood-sought-islamist-state-in-uae;

Said Nasser al-Teniji, “The UAE’s descent into oppression,” Guardian (London), October 2, 2012, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/oct/02/uae-descent-oppression.

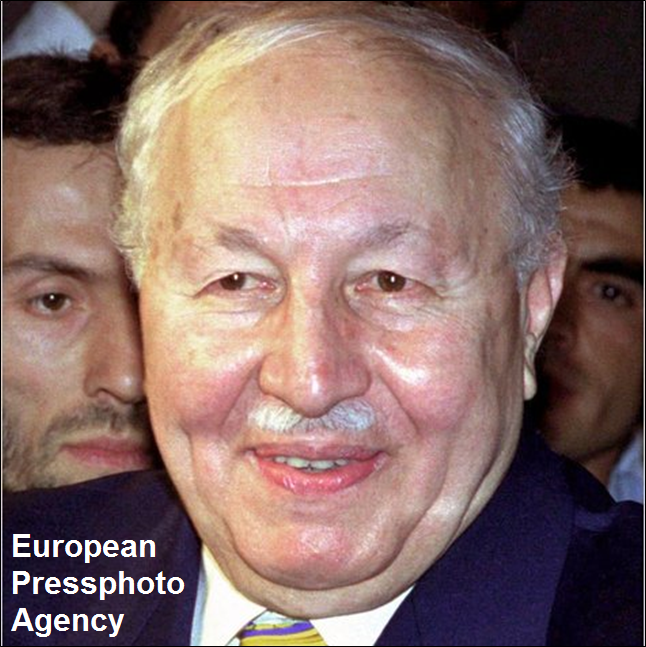

Necmettin Erbakan was an Islamist Turkish politician who founded a series of Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated political parties in Turkey. The strongest of these parties was the Welfare Party, which operated between 1983 and 1998.Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Welfare Party,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Welfare-Party;

“World: Analysis: Tukey Bans The Islamists,” BBC News, January 17, 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/48025.stm. Erbakan served as the Prime Minister of Turkey between 1996 and 1997,Stephen Kinzer, “Necmettin Erbakan, a Turkish Prime Minister, Dies at 84,” New York Times, February 28, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/01/world/europe/01erbakan.html. when he was forced out of power by the Turkish military. Following his ouster, Erbakan continued to form and rebrand Brotherhood-affiliated political parties in an effort to Islamize Turkish society.Stephen Kinzer, “Necmettin Erbakan, a Turkish Prime Minister, Dies at 84,” New York Times, February 28, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/01/world/europe/01erbakan.html.

Erbakan entered Turkish politics in 1969. That year, he wrote a manifesto titled “Milli Gorus,” or “National Perspective,” in which he revealed his methodology to turn Turkey into an Islamic state. Later that year, the ideology in his manifesto developed into the Islamist movement Milli Gorus, which reached Europe in the 1970s.David Vielhaber, “The Milli Gorus of Germany,” Hudson Institute, June 13, 2012, http://www.hudson.org/research/9879-the-milli-g-r-s-of-germany-;

David Vielhaber, “The Milli Gorus of Germany,” Hudson Institute, http://www.hudson.org/content/researchattachments/attachment/1268/vielhaber.pdf.

In 1983, Erbakan created the Brotherhood-affiliated Welfare Party after two of his previous political parties were shut down.Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Welfare Party,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Welfare-Party. Just over a decade later, in 1994, Erbakan led the Welfare Party to victory in local elections across Turkey—including in Istanbul and Ankara.Omer Taspinar, “Turkey: The New Model?” Brookings Institution, April 25, 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/research/turkey-the-new-model/. The Welfare Party’s popularity continued into 1995, when it became the ruling bloc in Parliament with Erbakan as Turkey’s Prime Minister.Omer Taspinar, “Turkey: The New Model?” Brookings Institution, April 25, 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/research/turkey-the-new-model/. Prime Minister Erbakan reportedly expressed a desire to form an “Islamic NATO,” and praised Palestinian terrorist organization Hamas.Steven Erlanger, “New Turkish Chief’s Muslim Tour Stirs U.S. Worry,” New York Times, August 10, 1996, http://www.nytimes.com/1996/08/10/world/new-turkish-chief-s-muslim-tour-stirs-us-worry.html?pagewanted=all.

In June 1997, the Turkish military ousted Erbakan after growing concerned with his desire to break from the secular status quo.Omer Taspinar, “Turkey: The New Model?” Brookings Institution, April 25, 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/research/turkey-the-new-model/;

“World: Analysis: Tukey Bans The Islamists,” BBC News, January 17, 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/48025.stm. The courts banned the Welfare Party in January 1998 for violating Turkey’s secular constitution, and further banned Erbakan from politics for five years.“World: Analysis: Tukey Bans The Islamists,” BBC News, January 17, 1998, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/48025.stm. His associates and followers used his policies and ideals to found the Felicity Party, a re-branded Welfare Party, in 2001. Erbakan was elected its leader in 2003, and again in 2010.Thomas Faulkner, “Necmettin Erbakan obituary,” Guardian (London), February 28, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/28/necmettin-erbakan-obituary;

“Erbakan elected as Saadet’s new leader,” Hurriyet Daily News (Turkey), October 17, 2010, http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/default.aspx?pageid=438&n=erbakan-elected-saadet-party8217s-new-leader-2010-10-17;

Selcan Hacaolgu, “Necmettin Erbakan, onetime Turkish prime minister, dies at 85,” Washington Post, March 3, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2011/03/03/AR2011030304804.html.

Erbakan died of heart failure in 2011.Stephen Kinzer, “Necmettin Erbakan, a Turkish Prime Minister, Dies at 84,” New York Times, February 28, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/01/world/europe/01erbakan.html. Prominent extremist figures attended his funeral, including Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal and the Brotherhood’s former spiritual guide Mohamed Mahdi Akef.Svante Cornell and M.K. Kaya, “The Naqshbandi-Khalidi Order and Political Islam in Turkey,” Hudson Institute, September 3, 2015, https://hudson.org/research/11601-the-naqshbandi-khalidi-order-and-political-islam-in-turkey.

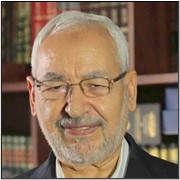

Rached Ghannouchi is the co-founder, leader, and president of Ennahda (a.k.a. El-Nahda), a Tunisian political party that emerged from the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood.Monica Marks, “Tunisia’s Ennahda: Rethinking Islamism in the context of ISIS and the Egyptian coup,” Brookings Institution, August 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Tunisia_Marks-FINALE.pdf; Marc Lynch, “Rached Ghannouchi: the FP interview,” Foreign Policy, December 5, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/12/05/rached-ghannouchi-the-fp-interview/. Ghannouchi has reportedly also associated with representatives of extremist groups, including the al-Qaeda-affiliated Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST)Bill Roggio, “‘Moderate’ Islamist Leader in Tunisia Strategizes with Al Qaeda-linked Salafists,” Long War Journal, October 16, 2012, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/10/moderate_islamist_le.php; Aaron Y. Zelin, “Tunisia: Uncovering Ansar al-Sharia,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 25, 2013, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/tunisia-uncovering-ansar-al-sharia. and global Islamist movement Hizb ut-Tahrir,Bill Roggio, “‘Moderate’ Islamist Leader in Tunisia Strategizes with Al Qaeda-linked Salafists,” Long War Journal, October 16, 2012, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/10/moderate_islamist_le.php. an extremist group banned from operating in at least 13 countries worldwide.“Hizb ut-Tahrir,” Counter Extremism Project, accessed May 31, 2016, https://www.counterextremism.com/threat/hizb-ut-tahrir. He has since renounced his and Ennahda’s Islamist positions and claims that “Islam is never in contradiction with democracy.”Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863; Carlotta Gall, “Tunisian Islamic Party Re-elects Moderate Leader,” New York Times, May 23, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/24/world/africa/tunisia-rachid-ghannouchi-ennahda.html.

Ghannouchi has received multiple international honors for his work in fostering Tunisia’s democratic transition. In 2011, Foreign Policy named him one of its Top 100 Thinkers. While visiting the United States to receive the honor, Ghannouchi met with multiple U.S. officials, journalists, and think tanks, including the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.Marc Lynch, “Rached Ghannouchi: the FP interview,” Foreign Policy, December 5, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/12/05/rached-ghannouchi-the-fp-interview/. In 2012, Ghannouchi shared the Chatham House Prize with Tunisian political leader Moncef Marzouki for their work in Tunisia’s democratic transition.“Chatham House Prize 2012 - Rached Ghannouchi and Moncef Marzouki,” Chatham House, accessed March 4, 2019, https://www.chathamhouse.org/chatham-house-prize/2012. In 2015, the International Crisis Group awarded Ghannouchi and Tunisian President Béji Caïd Essebsi the Founder’s Award for their work in peace-building.“Tunisia: Caïd Essebsi and Ghannouchi Receive International Crisis Group Founder's Award,” All Africa, October 27, 2015, https://allafrica.com/stories/201510280454.html.

Born in Tunisia in 1941 and trained as a high school philosophy teacher, Ghannouchi founded Ennahda’s predecessor, the Islamic Tendency Movement (ITM), in 1981, initially drawing inspiration for the party from the Muslim Brotherhood.Carlotta Gall, “Tunisian Islamic Party Re-elects Moderate Leader,” New York Times, May 23, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/24/world/africa/tunisia-rachid-ghannouchi-ennahda.html; Aidan Lewis, “Profile: Tunisia’s Ennahda Party,” BBC News, October 25, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15442859; James M. Markham, “Tunis Journal; A Song of Democracy in a Distinctly Islamic Key,” New York Times, April 14, 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/04/14/world/tunis-journal-a-song-of-democracy-in-a-distinctly-islamic-key.html. Ghannouchi formed his political views traveling through Syria, Egypt, France, and Iran. He was reportedly enamored with the 1979 Iranian revolution, though he later said the ITM was “in principle against executing people for their ideas” and condemned the Iranian government “if that is what is happening in Iran….”James M. Markham, “Tunis Journal; A Song of Democracy in a Distinctly Islamic Key,” New York Times, April 14, 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/04/14/world/tunis-journal-a-song-of-democracy-in-a-distinctly-islamic-key.html. Tunisian President Habib Bourguiba banned the ITM shortly after its creation and imprisoned Ghannouchi for four years.Lally Weymouth, “An interview with Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi, three years after the revolution,” Washington Post, December 12, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-interview-with-tunisias-rachid-ghannouchi-three-years-after-the-revolution/2013/12/12/7aaaaa5a-62cf-11e3-a373-0f9f2d1c2b61_story.html?utm_term=.f44bbc6e868d.

In 1987, Bourguiba arrested Ghannouchi and dozens of other Islamists on suspicions they were trying to create a Khomeinist-style revolution in Tunisia. Ghannouchi was sentenced to a life of hard labor. In November 1987, Zine al-Abdine Ben Ali overthrew Bourguiba. In May 1988, Ben Ali pardoned and freed Grannouchi and almost 3,000 other Islamists.James M. Markham, “Tunis Journal; A Song of Democracy in a Distinctly Islamic Key,” New York Times, April 14, 1989, https://www.nytimes.com/1989/04/14/world/tunis-journal-a-song-of-democracy-in-a-distinctly-islamic-key.html.

ITM rebranded as Ennahda in 1989 ahead of Tunisia’s parliamentary elections. Ennahda officially received 17 percent, making it the second-largest political party. Due to fraud allegations, however, some analysts placed the real estimate much higher. Ben Ali banned Ennahda in response to its electoral success, and Ghannouchi went into a 22-year exile in London.“Tunisia’s Ennahda distances itself from political Islam,” Al Jazeera, May 27, 2016, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/05/left-tunisia-ennahda-party-160526101937131.html; Aidan Lewis, “Profile: Tunisia's Ennahda Party,” BBC News, October 25, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-15442859; “Factbox: Who is Tunisia’s Islamist leader Rachid Ghannouchi?” Reuters, January 30, 2011, http://blogs.reuters.com/faithworld/2011/01/30/factbox-who-is-tunisias-islamist-leader-rachid-ghannouchi/. Ghannouchi returned to Tunisia in 2011 following the overthrow of Ben Ali in the early days of the Arab Spring. Ghannouchi positioned Ennahda to run in Tunisia’s parliamentary elections, though he did not himself run for office. That October, Ennahda won a plurality of the country’s vote.Ellen McLarney, “Why Arab Spring made life better in Tunisia, failed everywhere else,” Reuters, February 18, 2015, http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2015/02/18/why-arab-spring-made-life-better-in-tunisia-failed-everywhere-else/;

Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863;

“Final Tunisian Election results announced,” Al Jazeera, November 14, 2011, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2011/11/20111114171420907168.html. In the lead up to the elections, Ghannouchi and Ennahda promised to improve education, women’s rights, and religious freedom. Ghannouchi held up Turkey’s Justice and Development party (AKP) as an example of how an Islamic political party can rule in a secular country.David D. Kirkpatrick, “Tunisians Vote in a Milestone of Arab Change,” New York Times, October 23, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/24/world/africa/tunisians-cast-historic-votes-in-peace-and-hope.html. With the Muslim Brotherhood ascending in Egyptian politics at the same time as Ennahda, researchers and journalists asked Ennahda members about their relationship with the Brotherhood. In August 2011, Ghannouchi told the Brookings Institution that Ennahda looked more to the AKP than the Brotherhood as an example. Ennahda sought to make people love Islam by convincing them, not coercing them, he told Brookings.Monica Marks, “Tunisia’s Ennahda: Rethinking Islamism in the context of ISIS and the Egyptian coup,” Brookings Institution, August 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Tunisia_Marks-FINALE.pdf.

Ghannouchi and Ennahda have reportedly had a relationship with the terror group Ansar al-Sharia Tunisia (AST). The leaders who would go on to form AST reportedly met with Ennahda leaders while in prison prior to the Arab Spring. According to the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, AST leaders attended meetings at Ghannouchi’s home in 2011 at which he allegedly advised them to encourage AST youth to infiltrate Tunisia’s national army and National Guard. In 2012, Ghannouchi was caught on tape strategizing with AST leaders and advocating for control over the media and other civil institutions.Bill Roggio, “‘Moderate’ Islamist Leader in Tunisia Strategizes with Al Qaeda-linked Salafists,” Long War Journal, October 16, 2012, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/10/moderate_islamist_le.php; Aaron Y. Zelin, “Tunisia: Uncovering Ansar al-Sharia,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 25, 2013, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/tunisia-uncovering-ansar-al-sharia. In the video, Ghannouchi also claimed to have met with representatives of global Islamist movement Hizb ut-Tahrir.Bill Roggio, “‘Moderate’ Islamist Leader in Tunisia Strategizes with Al Qaeda-linked Salafists,” Long War Journal, October 16, 2012, http://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2012/10/moderate_islamist_le.php. Although Ennahda ultimately conceded to the Tunisian government’s decision to designate AST as a terrorist organization in August 2013, Ennahda reportedly continued to excuse AST’s violent activities for months beforehand until popular discontent and the growing threat of a political crisis motivated the party to change its stance.Aaron Y. Zelin and Vish Sakthivel, “Tunisia Designates Ansar al-Sharia,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 28, 2013, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/tunisia-designates-ansar-al-sharia.

From December 2011 to 2014, Ennahda members Hamadi Jebali and Ali Laarayedh served as successive interim prime ministers of Tunisia,Eileen Byrne, “Tunisia’s Ruling Islamist Party Ennahda Names New Prime Minister,” Guardian (London), February 22, 2013, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/feb/22/tunisia-ennahda-prime-minister;

“Tunisia PM Resigns as Part of Transition Plan,” Al Jazeera, January 9, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/01/tunisia-pm-resigns-as-part-transition-plan-201419145034687910.html. during which time the party steadily lost support among the Tunisian public.“Tunisian Confidence in Democracy Wanes,” Pew Research Center, October 15, 2014, http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/10/15/tunisian-confidence-in-democracy-wanes/; Michael Robbins, “Five years after the revolution, more and more Tunisians support democracy,” Washington Post, May 20, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/20/are-tunisians-more-optimistic-about-democracy-after-5-years-living-under-it/. The party voluntarily relinquished power in January 2014 after Ghannouchi struck a deal with secular political opponents.Carlotta Gall, “A Political Deal in a Deeply Divided Tunisia as Islamists Agree to Yield Power,” New York Times, December 16, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/17/world/africa/a-political-deal-in-a-deeply-divided-tunisia-as-islamists-agree-to-yield-power.html?module=inline; Carlotta Gall, “Tunisia’s Premier Resigns, Formally Ending His Party’s Rule,”

The party’s decline in popularity continued into mid-2016 when, in an apparent effort to revitalize the party, Ghannouchi publicly sought to rebrand Ennahda’s platform. In May 2016, Ennahda divorced itself from its Islamist agenda, pledging to pursue a “Muslim democracy” in place of an Islamic state.Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863. Ghannouchi claimed there was no longer justification for political Islam in Tunisia.Amberin Zaman, “Democrat or Islamist firebrand — who is Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi?” Al-Monitor, January 28, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/01/tunisia-ennahda-rached-ghannouchi-islamists-arab-spring.html#ixzz5glwJpydy.

Ennahda updated its official party platform in May 2016 to emphasize its commitment to working “within the framework of the republican system to contribute to the building of modern Tunisia, a prosperous and interdependent democracy” that embraces its religious identity and social justice.“Party Platform,” Ennahda, accessed March 1, 2019, http://www.ennahdha.tn/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%AF-%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%AD%D9%87-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A4%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%B4%D8%B1. The platform recognizes the Islamic character of Tunisia but does not call for enforcing Islamic rules on Tunisian society.Amberin Zaman, “Democrat or Islamist firebrand — who is Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi?” Al-Monitor, January 28, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/01/tunisia-ennahda-rached-ghannouchi-islamists-arab-spring.html#ixzz5glwJpydy. The party’s membership requirements call for members to be moral and virtuous, but do not require them to adhere to the Islamic faith.“Engagement,” Ennahda, accessed March 1, 2019, http://www.ennahdha.tn/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D9%86%D8%AE%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B7.

The party views its commitment to democratic values as necessary for the “struggle” for Arab unity and “the liberation of Palestine.”“Party Platform,” Ennahda, accessed March 1, 2019, http://www.ennahdha.tn/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%AF-%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%AD%D9%87-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A4%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%B4%D8%B1. Though the platform calls for “the liberation of Palestine,” it does not mention Israel or opposition to the Jewish state. During a 2011 meeting with the Washington Institute on Near East Policy, Ghannouchi declared that Ennahda objected to a constitutional amendment prohibiting normalization with Israel.“Concerning Mr. Rachid Ghannouchi’s Visit to The Washington Institute,” Washington Institute on Near East Policy, December 20, 2011, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/concerning-mr.-rachid-ghannouchis-visit-to-the-washington-institute. In a 2013 interview with the Washington Post, Ghannouchi denied that he had previously predicted the end of Israel. In the same interview, however, he claimed that Hamas is open to a two-state solution while Israel rejects one.Lally Weymouth, “An interview with Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi, three years after the revolution,” Washington Post, December 12, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-interview-with-tunisias-rachid-ghannouchi-three-years-after-the-revolution/2013/12/12/7aaaaa5a-62cf-11e3-a373-0f9f2d1c2b61_story.html?utm_term=.9e6f36711afe.

Ghannouchi has also refused to renounce ties with the global Brotherhood movement, casting further skepticism on the sincerity of his new platform.Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863. In November 2012, Ghannouchi attended an Islamist conference in Khartoum, Sudan, alongside Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal and Muslim Brotherhood Supreme Guide Mohammed Badie. Ghannouchi declared “the mother of the revolutions was the blessed Palestinian revolution.”Alexander Dziadosz, “Islamist leaders vow unity against Israel,” Reuters, November 15, 2012, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-palestinians-israel-islamists/islamist-leaders-vow-unity-against-israel-idUSBRE8AE1HC20121115. In a 2013 interview with the Washington Post, Ghannouchi denied belonging to the Brotherhood but admitted admiration for the Brotherhood’s former Egyptian president, Mohammed Morsi. Ghannouchi defended Morsi against accusations of abuses against protesters. According to Ghannouchi, the Egyptian media had become a mouthpiece for the military government.Lally Weymouth, “An interview with Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi, three years after the revolution,” Washington Post, December 12, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/an-interview-with-tunisias-rachid-ghannouchi-three-years-after-the-revolution/2013/12/12/7aaaaa5a-62cf-11e3-a373-0f9f2d1c2b61_story.html?utm_term=.f44bbc6e868d. In April 2016, a month before his announcement on Ennahda’s new direction, Ghannouchi attended a global Muslim Brotherhood conference in Istanbul.Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863. He has also continued to serve as a high-ranking member of several Islamist and Brotherhood-affiliated organizations in Europe tied to Qatar-based cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi, including the Dublin-based European Council for Fatwa and Research (ECFR)Jorgen Nielsen, Muslim Political Participation in Europe (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 221. and, according to Reuters, the International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS) as recently as 2017.“The Start of the General Assembly of the IUMS… and the Palestine and Gaza Cause Being Is Most Prominent in the Speeches Launched,” International Union of Muslim Scholars, August 21, 2014, http://iumsonline.org/en/iums123/news/h1240/; “Ghannoushi: Fundamentalists are a Danger for Tunisia,” International Union of Muslim Scholars, October 3, 2012, http://iumsonline.org/en/iums123/news/d2133/; “Seminar Discusses Women, Family in Tunisia,” International Union of Muslim Scholars, November 12, 2012, http://iumsonline.org/en/iums123/news/seminar-discusses-women-family-tunisia/; “Arab states blacklist Islamist groups, individuals in Qatar boycott,” Reuters, November 22, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-security/arab-states-blacklist-islamist-groups-individuals-in-qatar-boycott-idUSKBN1DM2WQ. In November 2017, multiple Gulf countries designated the IUMS as a terrorist organization.“Arab states blacklist Islamist groups, individuals in Qatar boycott,” Reuters, November 22, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-gulf-qatar-security/arab-states-blacklist-islamist-groups-individuals-in-qatar-boycott-idUSKBN1DM2WQ. Ennahda expressed surprise at the designation, asserting that the group is known for its honesty and tolerance.“Saudi Arabia denies including Tunisia’s Ghannouchi on ‘terrorist list,’” Middle East Monitor, November 25, 2017, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20171125-saudi-arabia-denies-including-tunisias-ghannouchi-on-terrorist-list/.

Ghannouchi continues to lead Ennahda, though the party is reportedly not united behind his leadership. Critics within the party argue that he has betrayed its Islamist ideals. In a 2016 piece for Foreign Affairs, Ghannouchi wrote that Islamic values still guide Ennahda, but the party is committed to democracy and religious freedom.Rached Ghannouchi, “From Political Islam to Muslim Democracy,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/tunisia/political-islam-muslim-democracy.

Despite Ennahda’ formal—and seemingly major—platform change in May 2016, Ghannouchi reportedly told Ennahda party members that same month that he was “astounded by those who want to distance religion from national [i.e. political] life.”Zvi Bar’el, “Tunisia Could Be on Verge of New Revolution: Separating Religion and Politics,” Ha’aretz (Tel Aviv), May 28, 2016, http://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/.premium-1.721863. In September 2017, both Tunisian politician Mohsen Marzouk and Tunisian President Beji Caid Essebsi criticized Ennahda for failing to reject its traditional Islamist vision and become more of a civic party.Amel al-Hilali, “Tunisia’s Ennahda struggles to shake political Islam identity,” Al Monitor, December 13, 2017, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/12/tunisia-ennahda-muslim-brotherhood-terrorist-political-islam.html; “Mohsen Marzouq: Ennahda has not been able to turn into a civil movement,” Kapitalis, September 23, 2017, http://www.kapitalis.com/anbaa-tounes/2017/09/23/%D9%85%D8%AD%D8%B3%D9%86-%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%B2%D9%88%D9%82-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%87%D8%B6%D8%A9-%D9%84%D9%85-%D8%AA%D8%AA%D9%85%D9%83%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%AD%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%A5%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%AD/; Ahmed Nahdif, “Tunisia’s next elections will put governing alliance to test,” Al Monitor, September 19, 2017, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/09/tunisia-alliance-nidaa-tunis-islamist-ennahda.html.

Ennahda still supports what could be considered traditional Islamist values. For example, Ennahda agreed to guarantee gender equality while helping draft Tunisia’s constitution in 2014. But in August 2018, Ennahda rejected a presidential initiative to grant gender equality in Tunisia’s inheritance law, which allows for a man to receive twice as much of an inheritance as a woman in accordance with sharia.“Tunisia: Ennahda Rejects Inheritance Equality,” Human Rights Watch, September 6, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/09/06/tunisia-ennahda-rejects-inheritance-equality. Ennahda’s Shura Council—the party’s main governing body—declared that it supports efforts to guarantee women’s rights “in a way that does not contradict the peremptory texts of religion and the provisions of the Constitution.”“Final statement of the 21st session of the Shura Council of the Renaissance Movement,” Ennahda, August 26, 2018, http://www.ennahdha.tn/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A9-21-%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AC%D9%84%D8%B3-%D8%B4%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%89-%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%87%D8%B6%D8%A9.

Ghannouchi has publicly defended Ennahda’s commitment to religious freedoms and blamed criticism on a “media war” trying to influence public opinion ahead of Tunisian elections.Amberin Zaman, “Democrat or Islamist firebrand — who is Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi?” Al-Monitor, January 28, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/01/tunisia-ennahda-rached-ghannouchi-islamists-arab-spring.html#ixzz5glwJpydy; “Tunisia declares Ansar al-Sharia a terrorist group,” BBC News, August 27, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-23853241. In a January 2019 Al-Monitor interview, he pointed to Ennahda’s role in legally banning AST in August 2013 under the Ennahda-led government. He declared: “There is only one Islam, but we believe it is a flexible religion that interacts with each environment with each age.”Amberin Zaman, “Democrat or Islamist firebrand — who is Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi?” Al-Monitor, January 28, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/01/tunisia-ennahda-rached-ghannouchi-islamists-arab-spring.html#ixzz5glwJpydy; “Tunisia declares Ansar al-Sharia a terrorist group,” BBC News, August 27, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-23853241. Ghannouchi has also continued to praise Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as a role model for Ennahda. Several Tunisia analysts have questioned whether Ghannouchi and Ennahda are sincere in their praise of political and religious freedom or if they are paying lip service to these values in order to avoid a second revolution that would remove them from power.Amberin Zaman, “Democrat or Islamist firebrand — who is Tunisia’s Rachid Ghannouchi?” Al-Monitor, January 28, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/01/tunisia-ennahda-rached-ghannouchi-islamists-arab-spring.html#ixzz5glwJpydy.

With presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled in September and October of 2019, Ennahda continued to declare candidates. In July 2019, Ghannouchi announced he would run in Tunisia’s upcoming parliamentary elections.“Tunisia: Ennahda party leader to stand in parliamentary polls,” Africa News, July 21, 2019, https://www.africanews.com/2019/07/21/tunisia-ennahda-party-leader-to-stand-in-parliamentary-polls/. The following month, Ennahda announced it would field its deputy leader, Abdelfattah Mourou, in Tunisia’s presidential elections.“Tunisia’s Ennahda names its first-ever candidate for presidential elections,” France 24, August 7, 2019, https://www.france24.com/en/20190807-tunisia-ennahda-presidential-elections-Abdel-Fattah-Mourou. Mourou came in third place in a presidential run-off election on September 15, 2019, with 12.9 percent of the vote. With their candidate lacking a clear path to the presidency, Ennahda announced its support for Kais Saied, who won 18.4 percent of the vote.“Moderate Islamist Ennahda backs Saied in Tunisia’s presidential run-off,” Reuters, September 19, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-tunisia-election-islamists-idUKKBN1W42VA. Ennahda fared better in Tunisia’s parliamentary elections on October 6, 2019, winning 52 seats. Though it lost 17 seats from the 2014 election, Ennahda still won the most seats in the country’s 217-seat parliament.“Tunisia’s moderate Islamist party Ennahda to lead fractured new parliament,” Reuters, October 9, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-tunisia-election-results-idUSKBN1WO2PD. Among Ennahda’s candidates, Ghannouchi was elected to parliament. He was elected speaker of parliament on November 13.“Tunisia parliament elects Ennahdha’s Rachid Ghannouchi as speaker,” Al Jazeera, November 13, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/13/tunisia-parliament-elects-ennahdhas-rachid-ghannouchi-as-speaker.

In July 2020, Free Constitutional party leader Abir Moussi accused Ghannouchi of serving the agenda of the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as foreign powers such as Turkey and Qatar. In mid-July 2020, Tunisian political parties opposed to Ennahda sought to launch a no-confidence vote against Ghannouchi.Tarek Amara, “Tunisian parties seek to oust parliament speaker, Islamists want new government,” Reuters, July 12, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-tunisia-politics/tunisian-parties-seek-to-oust-parliament-speaker-islamists-want-new-government-idUSKCN24D0NL. A no-confidence vote on Ghannouchi failed on July 30.Ali Abo Rezeg, “Tunisia: No-confidence vote fails to remove Ghannouchi,” Anadolu Agency, July 30, 2020, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/tunisia-no-confidence-vote-fails-to-remove-ghannouchi/1927351.

On July 25, 2021, Saied dismissed Prime Minister Hicham Mechichi and suspended the country’s parliament.“Tunisia’s president accused of ‘coup’ after dismissing PM,” Al Jazeera, July 25, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/25/tunisias-president-dismisses-prime-minister-after-protests. Ghannouchi condemned the move as a “a coup against the revolution and constitution,” while Tunisians took to the streets in protest.“Tunisia’s president accused of ‘coup’ after dismissing PM,” Al Jazeera, July 25, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/25/tunisias-president-dismisses-prime-minister-after-protests. Ghannouchi initially led a sit-in outside of parliament and called for protests similar to the Arab Spring protests of 2011. He soon after called for calm and dialogue, while an Ennahda spokesman said there was an “awareness within Ennahda that we need to avoid escalation and must keep calm in our democracy.”“Tunisia’s president accused of ‘coup’ after dismissing PM,” Al Jazeera, July 25, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/25/tunisias-president-dismisses-prime-minister-after-protests; Tarek Amara and Angus Mcdowall, “Analysis: Tunisia’s political crisis poses existential test for Islamist party,” Reuters, July 29, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/tunisias-political-crisis-poses-existential-test-islamist-party-2021-07-29/.

Mohammad Hekmat Walid has served as the leader, or the “comptroller general,” of the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria since November 2014.Agence France-Presse, “Syria Muslim Brotherhood appoints new leader,” Al Monitor, November 7, 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/ar/contents/afp/2014/11/syria-conflict-islam-politics-opposition.html. Hailing from Latakia, Syria, Walid is the 12th leader of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood since the group’s founding in 1945. He is an ophthalmologist by training and is reported to have studied in the United Kingdom.“The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed May 16, 2016, http://carnegieendowment.org/syriaincrisis/?fa=48370;

Hazem Kandil, Inside the Brotherhood (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press, 2015), 154, “Q&A: ‘We want to build a new Syria,’” Al Jazeera, May 26, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2015/01/qa-want-build-new-syria-20151146413892728.html.

Walid left Syria in the 1970sDasha Afanasieva, “Banned in Syria, Muslim Brotherhood members trickle home,” Reuters, May 7, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-brotherhood-idUSKBN0NR20Y20150507. and was a long-time resident of Saudi Arabia Raphaël Lefèvre, “New Leaders for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 11, 2014, http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/12/11/new-leaders-for-syrian-muslim-brotherhood. before moving to Istanbul, Turkey, around 2014.Raphaël Lefèvre, “New Leaders for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 11, 2014, http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/12/11/new-leaders-for-syrian-muslim-brotherhood. In March 2014, he was elected head of the Brotherhood’s Waad political party in Syria.Raphaël Lefèvre, “New Leaders for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 11, 2014, http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/12/11/new-leaders-for-syrian-muslim-brotherhood. That November, Walid officially left the Waad party and was elected general comptroller of the Syrian Brotherhood.“Mohamed Hikmat Walid Elected Comptroller-General for Syria Muslim Brotherhood,” Ikhwanweb: The Muslim Brotherhood’s Official English web site, November 7, 2014, http://www.ikhwanweb.com/article.php?id=31886;

Raphaël Lefèvre, “New Leaders for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 11, 2014, http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/12/11/new-leaders-for-syrian-muslim-brotherhood.

In mid-2015, Walid told Reuters in an interview that the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood was encouraging its members—many of whom had been in exile in Turkey since the 1980s—to return to Syria and re-establish the group there amid the Syrian civil war.Dasha Afanasieva, “Banned in Syria, Muslim Brotherhood members trickle home,” Reuters, May 7, 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-brotherhood-idUSKBN0NR20Y20150507. According to Brotherhood analyst Raphaël Lefèvre, Walid is known for his “diplomatic skills and compromising spirit.”Raphaël Lefèvre, “New Leaders for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 11, 2014, http://carnegie-mec.org/2014/12/11/new-leaders-for-syrian-muslim-brotherhood.

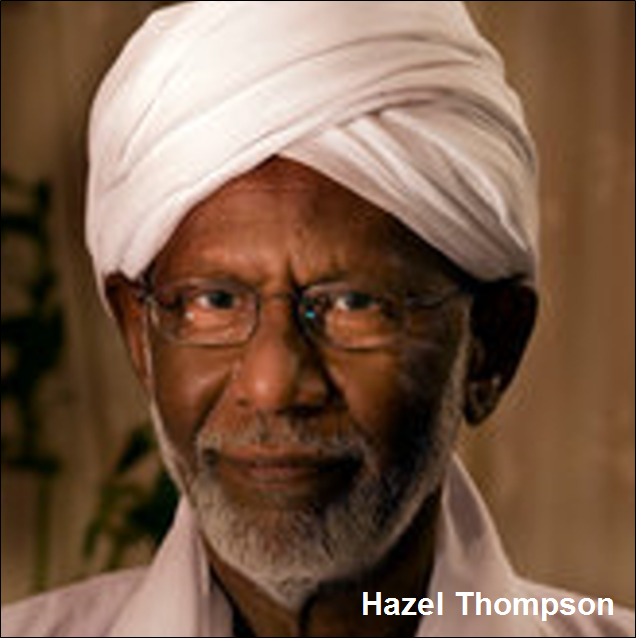

Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi was an Islamist Sudanese politician and a longtime advisor to incumbent Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir.Lawrence Joffe, “Hassan al-Turabi obituary,” Guardian (London), March 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/11/hassan-al-turabi-obituary. Turabi advocated sharia (Islamic law) in Sudan and was linked to Osama bin Laden, inviting him in 1990 to relocate his terrorist network to Sudan. Turabi was a member of the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan, and led several Brotherhood-linked political parties including the Islamic Charter Front (ICF), the National Islamic Front (NIF), and the Popular National Congress Party (PNCP).Lawrence Joffe, “Hassan al-Turabi obituary,” Guardian (London), March 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/11/hassan-al-turabi-obituary;

“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Turabi is also believed to have had connections with al-Qaeda, Hamas, and Hezbollah. He died in March 2016.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.

Turabi was born in 1932 in the eastern Sudanese town of Kassala. He reportedly attended Islamic schools throughout his childhood before studying law in Khartoum, receiving a Master’s degree in London, and then a PhD at Sorbonne University in Paris.“Profile: Sudan’s Islamist leader,” BBC News, January 15, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3190770.stm. Following his schooling, Turabi became the dean of the School of Law at the University of Khartoum.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.

In 1963, Turabi and leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan—which had formed in 1949—established the Brotherhood’s political party, the Islamic Charter Front (ICF). Turabi was soon elected secretary general of the party.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. The ICF advocated an Islamist constitution and operated on university campuses in an effort to recruit younger, educated members.“Islamic Charter Front,” Oxford Islamic Studies, accessed October 11, 2016, http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e1095.

Turabi’s ICF was dissolved in 1969 following a military coup led by socialist Nafar al-Numayri.“Muslim Brotherhood in Sudan,” Oxford Islamic Studies, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e1641;

“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Following Numayri’s rule, Turabi reorganized the former ICF leadership and formed a new political party, the National Islamic Front (NIF), serving as its secretary general. He was appointed Sudan’s minister of justice and attorney general in May 1988, and then minister of foreign affairs in December of that year. Turabi stepped down from these positions in 1989, when he refused to support a peace agreement that advocated secularism in the south Sudan region.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Turabi backed a 1989 military coup, which placed General Omar al Bashir in power of Sudan and in charge of the NIF.“National Congress Party (NCP),” Sudan Tribune, accessed September 30, 2016, http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?mot137;

“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Turabi reportedly advised Bashir in his efforts to fashion a government in accordance with Islamic law.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm; “Profile: Sudan’s Islamist leader,” BBC News, January 15, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3190770.stm.

As Bashir’s right-hand man and advisor, Turabi was given the autonomy to advance the NIF’s Islamist agenda by establishing ties with a number of extremist individuals, most notoriously Osama bin Laden, who was married to Turabi’s niece. In 1989, Turabi reportedly invited bin Laden to “transplant his whole organization to Sudan,” according to findings released by the United States 9/11 Commission report.Greg Botelho, Sudanese Islamist leader, bin Laden ally Hassan al-Turabi dies,” CNN, March 5, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/03/05/africa/sudan-hassan-al-turabi-dies/;

Lawrence Joffe, “Hassan al-Turabi obituary,” Guardian (London), March 11, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/11/hassan-al-turabi-obituary. Bin Laden accepted the invitation and promised to fight against Christian separatists in southern Sudan in exchange for safe haven.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.

Turabi was also linked to a number of extremist organizations. In 1991, Turabi founded the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress (PAIC), an annual conference that brought together global militant Islamist leaders. The PAIC congregations are believed to have hosted leaders and representatives from al-Qaeda, the Palestine Liberation Organization, Hamas, and Hezbollah.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.

In addition to aligning himself with extremist groups, Turabi is believed to have carried out gross human rights violations, including the conscription of child soldiers. For example, in the 1990s, Turabi organized the “Civilization Project,” a program which indoctrinated youth to high-school-aged boys whom he forced to fight against the Christian population in southern Sudan.Ahmed Kodouda, “Sudan’s Islamist Resurrection: al-Turabi and the Successor Regime,” African Arguments, February 24, 2016, http://africanarguments.org/2016/02/24/sudans-islamist-resurrection-al-turabi-and-the-successor-regime/;

“Sudan’s Islamist Regime: The Rise and Fall of the ’Civilization Project’,” Democracy First Group, accessed November 3, 2016, http://www.democracyfirstgroup.org/sudans-islamist-regime-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-civilization-project/. The program also included the purging of non-Islamists from government entities, including civil service, military, and security functions. Non-Islamists were reportedly subject to torture as part of Turabi’s push to implement sharia in Sudan.Ahmed Kodouda, “Sudan’s Islamist Resurrection: al-Turabi and the Successor Regime,” African Arguments, February 24, 2016, http://africanarguments.org/2016/02/24/sudans-islamist-resurrection-al-turabi-and-the-successor-regime/.

The partnership between Bashir and Turabi dissolved soon after Bashir reorganized the NIF to form the National Congress Party (NCP) in 1998. In December 1999, following a yearlong power struggle, Bashir stripped Turabi of his position of secretary general in the NCP.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Turabi then split from that party with a group of followers and formed the Popular National Congress Party (PNCP), which continues to denounce both secularism and democracy and promoted an openly Islamist agenda. The PNCP has since struggled to establish itself as a robust political party, winning marginal parliamentary seats each election cycle.Popular Congress Party, Popular National Congress Party (PNCP),” Global Security, accessed October 11, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/political-parties-pcp.htm.

Turabi was continuously arrested by the Sudanese government following his split from the NCP. He was arrested three separate times for coup allegations in February of 2001, March of 2004, and March of 2008.“Profile: Sudan’s Islamist leader,” BBC News, January 15, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/3190770.stm;

“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm. Following his 2008 arrest, Turabi was imprisoned again in March 2010 for condemning the national elections as fraudulent.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.In Turabi’s final arrest, he was detained by Sudanese officials for several months, alongside eight other PNCP leaders, in January 2011 for encouraging an anti-Bashir uprising in Khartoum.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm

In March 2015, Turabi was reportedly hospitalized after collapsing in his office. A year later, Turabi died on March 5, 2016 from a heart attack. His funeral was reportedly attended by thousands of mourners who sympathized with his political and ideological views.“Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi,” Global Security, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/sudan/turabi.htm.

Ibrahim Mounir was the London-based former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood. He previously served as the secretary-general of the Brotherhood’s international organization, comprising the group’s global affiliates, which officially exist in 18 countries including Egypt.Samuel Tadros, “The Brotherhood Divided,” Hudson Institute, April 20, 2015, http://www.hudson.org/research/11530-the-brotherhood-divided; Dr. Nathan Brown, “The Muslim Brotherhood,” Congressional Testimony, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 13, 2011, 10-11, http://carnegieendowment.org/files/0413_testimony_brown.pdf. Mounir ascended to the role of acting general guide in September 2020, following the arrest of the previous acting guide, Mahmoud Ezzat, in August 2020.“Egypt: Wanted Brotherhood leader Mahmoud Ezzat arrested,” Gulf News, August 28, 2020, https://gulfnews.com/world/mena/egypt-wanted-brotherhood-leader-mahmoud-ezzat-arrested-1.73483156; “Muslim Brotherhood Statement on the Arrest of Acting Chairman Dr. Mahmoud Ezzat,” Ikhwanweb, September 3, 2020, https://www.ikhwanweb.com/article.php?id=32966. He was dismissed from the role in November 2021, sparking an internal row over the group’s leadership.“Former Secretary General Mahmoud Hussein dismissing Mounir from the position of Brotherhood guide,” Arab Observer, November 26, 2021, https://www.arabobserver.com/former-secretary-general-mahmoud-hussein-dismissing-mounir-from-the-position-of-brotherhood-guide/. Mounir died in November 2022 at the age of 85.“Acting leader of Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood dies at 85 – statement,” Reuters, November 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/acting-leader-egypts-muslim-brotherhood-dies-85-statement-2022-11-04/.

Mounir, who was born in Egypt, had been living in exile in the United Kingdom since the 1990s.Al-Masry Al-Youm, “Political refugee to return to Egypt, oversee MB development,” Egyptian Independent, July 23, 2012, http://www.egyptindependent.com//news/political-refugee-return-egypt-oversee-mb-development. In August 2015, Mounir claimed he had not returned to Egypt since 1987.“A talk with the Muslim Brotherhood’s Ibrahim Munir,” Asharq Al-Awsat (London), http://english.aawsat.com/2011/01/article55247947/a-talk-with-the-muslim-brotherhoods-ibrahim-munir. A longtime member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Mounir had been in and out of Egyptian prison since his first arrest in the 1950s under President Gamal Abdel Nasser.Ian Black, “Muslim Brotherhood leader hits out at Britain after Sisi sworn in,” Guardian (London), June 8, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/08/muslim-brotherhood-hits-out-britain-sisi-egypt. Nasser imprisoned Mounir in 1955 when he was 17 years old. Mounir was sentenced to five years of hard labor but served seven years before he was released. In 1965, Egyptian authorities arrested Mounir for reviving the Muslim Brotherhood. He was released after nine years, after which he left Egypt.“Meshaal describes late Brotherhood Guide as ‘great supporter of Palestine,’” Middle East Monitor, November 8, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20221108-meshaal-describes-late-brotherhood-guide-as-great-supporter-of-palestine/. In the 1990s, Mounir was granted political asylum by the British government after reportedly receiving death threats from Egyptian security forces.Al-Masry Al-Youm, “Political refugee to return to Egypt, oversee MB development,” Egyptian Independent, July 23, 2012, http://www.egyptindependent.com//news/political-refugee-return-egypt-oversee-mb-development. In January 2011, he was charged in absentia by the pre-revolution Egyptian government’s director of public prosecution with money laundering and fundraising for the Muslim Brotherhood abroad.“A talk with the Muslim Brotherhood’s Ibrahim Munir,” Asharq Al-Awsat (London), http://english.aawsat.com/2011/01/article55247947/a-talk-with-the-muslim-brotherhoods-ibrahim-munir.

Following the 2011 Egyptian revolution, then-Deputy Supreme Guide of the Egyptian Brotherhood Khairat el-Shater reportedly tasked Mounir with overseeing the Brotherhood’s development, including improving its image and infrastructure.Al-Masry Al-Youm, “Political refugee to return to Egypt, oversee MB development,” Egyptian Independent, July 23, 2012, http://www.egyptindependent.com//news/political-refugee-return-egypt-oversee-mb-development. Mounir was allegedly responsible for running IkhwanWeb, the Muslim Brotherhood’s official English-language website, and its weekly journal Risalat al-Ikhwan.Hany Ghoraba, “Ibrahim Munir, the Man Who Keeps the Muslim Brotherhood Alive,” Algemeiner, December 26, 2017, https://www.algemeiner.com/2017/12/26/ibrahim-munir-the-man-who-keeps-the-muslim-brotherhood-alive/. In 2014, Mounir was allegedly instrumental in convincing former British Prime Minister David Cameron not to ban the Muslim Brotherhood from the United Kingdom.Hany Ghoraba, “Ibrahim Munir, the Man Who Keeps the Muslim Brotherhood Alive,” Algemeiner, December 26, 2017, https://www.algemeiner.com/2017/12/26/ibrahim-munir-the-man-who-keeps-the-muslim-brotherhood-alive/. In August 2015, Mounir denied reports from Egyptian and Arab newspapers that he had become the Brotherhood’s supreme guide. In his statement, Mounir confirmed that Mahmoud Ezzat—who had taken over from Mohammed Badie in August 2013 after the latter was imprisoned—remained the acting supreme guide.“Ibrahim Munir denies reports he is now Brotherhood’s Supreme Guide,” Middle East Monitor, August 10, 2015, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20150810-ibrahim-munir-denies-reports-he-is-now-brotherhoods-supreme-guide-2/;

“Mahmoud Ezzat named Muslim Brotherhood’s new leader,” Al Arabiya, August 20, 2013, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2013/08/21/Mahmoud-Ezzat-named-Muslim-Brotherhood-s-new-leader.html.

In December 2015, the British government under Prime Minister David Cameron published a review of the Muslim Brotherhood movement and its suspected affiliated groups operating inside the United Kingdom.Alan Travis and Randeep Ramesh, “Muslim Brotherhood are possible extremists, David Cameron says,” Guardian (London), December 17, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/dec/17/uk-will-not-ban-muslim-brotherhood-david-cameron-says. British Ambassador to Saudi Arabia Sir John Jenkins met with Mounir to consult on the review. Mounir reportedly threatened to take legal measures if the review casted a negative light on the Brotherhood. Ian Black, “Muslim Brotherhood leader hits out at Britain after Sisi sworn in,” Guardian (London), June 8, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/08/muslim-brotherhood-hits-out-britain-sisi-egypt. Mounir further warned that if the review resulted in the ban of the group, Muslim communities would feel marginalized and it would open doors for “all options,” possibly violence.Tom Coghlan, “Ban on Muslim Brotherhood ‘will increase terrorism risk’,” Times (London), April 5 2014, http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/politics/article4055311.ece.

On July 24, 2017, a Cairo criminal court added Mounir, along with 295 other individuals, to the state terror list and accused him of plotting attacks from abroad.“A talk with the Muslim Brotherhood’s Ibrahim Munir,” Asharq Al-Awsat (London), January 12, 2011, http://english.aawsat.com/2011/01/article55247947/a-talk-with-the-muslim-brotherhoods-ibrahim-munir;

Al-Masry Al-Youm, “Political refugee to return to Egypt, oversee MB development,” Egypt Independent (Cairo), July 23, 2012, http://www.egyptindependent.com//news/political-refugee-return-egypt-oversee-mb-development.

Egyptian authorities arrested Ezzat in August 2020. The following month, the Brotherhood named Mounir as the new acting general guide, also referred to as the deputy general guide, making him the leader of both the Brotherhood abroad and in Egypt. Mounir then announced the dissolution of the Brotherhood’s Guidance Office and its reorganization into a new managing committee operating from abroad.“Muslim Brotherhood: ‘Ibrahim Mounir is the new acting general guide,’” Middle East Monitor, last updated September 21, 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200916-muslim-brotherhood-ibrahim-mounir-is-the-new-acting-supreme-guide/; “Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood forms managing committee,” Anadolu Agency, September 17, 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/egypts-muslim-brotherhood-forms-managing-committee/1976780. The international Brotherhood and the Brotherhood in Egypt reportedly rallied behind Mounir’s leadership.“Egypt Muslim Brotherhood align with new acting supreme guide,” Middle East Monitor, September 17, 2020, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200917-egypt-muslim-brotherhood-align-with-new-acting-supreme-guide/, but cracks emerged the following year.

In October 2021, Mounir suspended six senior members of the Brotherhood who allegedly rejected the results of the Brotherhood’s internal elections. Also, that month, members of the General Shura Council of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood Abroad renewed their “pledge of allegiance” to Mounir as acting director and the deputy of the Brotherhood’s general guide. Talaat Fahmi was also dismissed as the Brotherhood’s spokesman and Mounir was named the only spokesman for the group, though a replacement for Fahmi was planned.“Muslim Brotherhood suspends 6 senior members,” Middle East Monitor, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20211011-muslim-brotherhood-suspends-6-senior-members/; October 11, 2021, “Muslim Brotherhood renews confidence in deputy head Mounir,” Middle East Monitor, October 14, 2021, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20211014-muslim-brotherhood-renews-confidence-in-deputy-head-mounir/. On November 25, 2021, former Secretary-General Mahmoud Hussein announced the Brotherhood’s General Shura Council had met and decided to dismiss Mounir. The council invalidated Mounir’s suspension of Brotherhood leaders in October. Hussein announced a temporary committee to carry out the responsibilities of the Brotherhood’s acting guide.“Former Secretary General Mahmoud Hussein dismissing Mounir from the position of Brotherhood guide,” Arab Observer, November 26, 2021, https://www.arabobserver.com/former-secretary-general-mahmoud-hussein-dismissing-mounir-from-the-position-of-brotherhood-guide/. In December, the Scholars Committee of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood called for support and cooperation with acting supreme guide Mounir in order to overcome the obstacles facing the group.“Muslim Brotherhood scholars call to support Deputy Supreme Guide Mounir,” Middle East Monitor, December 4, 2021, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20211204-muslim-brotherhood-scholars-call-to-support-deputy-supreme-guide-mounir/. On January 30, 2022, the Brotherhood rejected the creation of a committee to carry out the role of the supreme guide. The Brotherhood accused “some members” of “violating its regulations and rejecting all attempts to unite the ranks.”“Muslim Brotherhood slams ‘members’ who bring division to group,” Middle East Monitor, January 31, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220131-muslim-brotherhood-slams-members-who-bring-division-to-group/. The Brotherhood announced all members seeking to divide the group would be “disowned.”“Muslim Brotherhood slams ‘members’ who bring division to group,” Middle East Monitor, January 31, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220131-muslim-brotherhood-slams-members-who-bring-division-to-group/.

In a July 2022 interview with Reuters, Mounir declared the Brotherhood did not seek to topple Egypt’s current government, which had previously outlawed the Brotherhood. Mounir emphasized the Brotherhood’s total rejection of violence. In the interview, published on July 29, Mounir also claimed the Brotherhood also “rejected the struggle for power” in Egypt, “even if between political parties through elections…”Dominic Evans, “Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood rejects ‘struggle for power’, exiled leader says,” Reuters, July 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/egypts-muslim-brotherhood-rejects-struggle-power-exiled-leader-says-2022-07-29/. That month, Mounir also reportedly announced his full withdrawal from political life.“Muslim Brotherhood Announces ‘Overcoming Power Struggle,’ Denies Concluding Deal with Cairo,” Asharq al-Awsat (London), October 16, 2022, https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/3934081/muslim-brotherhood-announces-%E2%80%98overcoming-power-struggle%E2%80%99-denies-concluding-deal. On November 4, 2022, he died in London at the age of 85.“Deputy supreme guide of Muslim Brotherhood dies in London,” Middle East Monitor, November 4, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20221104-deputy-supreme-guide-of-muslim-brotherhood-dies-in-london/; “Acting leader of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood dies at 85 – statement,” Reuters, November 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/acting-leader-egypts-muslim-brotherhood-dies-85-statement-2022-11-04/; “Leading figure in Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood dies at 85,” Associated Press, November 4, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/europe-middle-east-africa-religion-egypt-adedc1541095344cd7580b033232fcc0. Former Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal described Mounir as a great supporter of Hamas and Palestine.“Meshaal describes late Brotherhood Guide as ‘great supporter of Palestine,’” Middle East Monitor, November 8, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20221108-meshaal-describes-late-brotherhood-guide-as-great-supporter-of-palestine/.

Egypt added Ibrahim Mounir to its State Terror List in July 2017.“Two Leading Brotherhood Figures among 296 names added to Egypt’s terror list,” Ahram Online, August 30, 2017, http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/276301/Egypt/Politics-/Two-leading-Brotherhood-figures-among--names-added.aspx.

Libyan politician Mohamed Sowan has served as the leader of the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Justice and Construction Party (JCP) since its formation in March 2012.Political Handbook of the World 2015, ed. Tom Lansford, (New York: SAGE, 2015), https://books.google.com/books?id=yNGfBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false. He was previously held as a prisoner of war for eight years under Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi due to his involvement with the Muslim Brotherhood.Political Handbook of the World 2015, ed. Tom Lansford, (New York: SAGE, 2015), https://books.google.com/books?id=yNGfBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false;

Mary Fitzgerald, “Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood Struggles to Grow,” Foreign Policy, May 1, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/01/libyas-muslim-brotherhood-struggles-to-grow/. According to an internal document released by the U.S. Department of State in 2012, Sowan “wields significant influence as the head of the…most influential Islamist party in Libya.”“US document reveals cooperation between Washington and Brotherhood,” Gulf News (Libya), June 18, 2014, http://gulfnews.com/news/mena/libya/us-document-reveals-cooperation-between-washington-and-brotherhood-1.1349207.

In the 2012 national Libyan elections, the JCP won 17 seats and became the second-largest party in the government, outsized only by the National Forces Alliance (NFA).Political Handbook of the World 2015, ed. Tom Lansford, (New York: SAGE, 2015), https://books.google.com/books?id=yNGfBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false. Under Sowan, the JCP has refused to cooperate with the NFA—a coalition and militia comprised of approximately 60 political parties and over 100 NGOs favoring more liberal, yet still Islamist, policies.Political Handbook of the World 2015, ed. Tom Lansford, (New York: SAGE, 2015), https://books.google.com/books?id=yNGfBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false;

Anas El Gomati, “Libya’s Islamists and the 17 February Revolution,” in Routledge Handbook of the Arab Spring: Rethinking Democratization, ed. Larbi Sadiki, (New York: Routledge, 2015), 131;

Mary Fitzgerald, “Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood Struggles to Grow,” Foreign Policy, May 1, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/01/libyas-muslim-brotherhood-struggles-to-grow/.

JCP members convened at a congress meeting in April 2014 and re-elected Sowan as the party’s leader.Mary Fitzgerald, “Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood Struggles to Grow,” Foreign Policy, May 1, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/01/libyas-muslim-brotherhood-struggles-to-grow/. The JCP’s support waned in Libya’s June 2014 general elections, but the party refused to transition power to the House of Representatives. This refusal made the JCP the ruling party of the Tripoli-based General National Congress.Political Handbook of the World 2015, ed. Tom Lansford, (New York: SAGE, 2015), https://books.google.com/books?id=yNGfBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false. Analysts suggest that the JCP’s affiliation with the Brotherhood, particularly with Sowan as its head, is limiting the party’s appeal among the greater Libyan populace.Mary Fitzgerald, “Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood Struggles to Grow,” Foreign Policy, May 1, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/05/01/libyas-muslim-brotherhood-struggles-to-grow/.

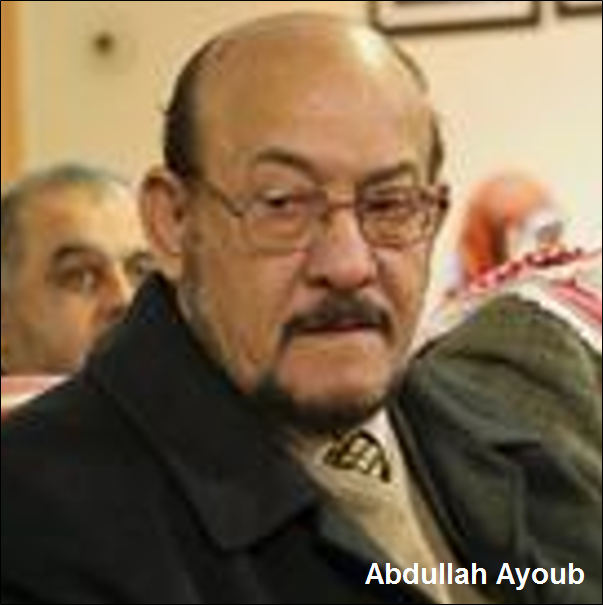

Abdul Majid Thuneibat is the former leader of Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood Society (MBS), the reformist organization that broke away from the Muslim Brotherhood Group (MBG) in 2015 and declared itself Jordan’s only official Muslim Brotherhood representative.Khetam Malkawai, “New leaders of Brotherhood demand control over assets,” Jordan Times (Amman), March 7, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/new-leaders-brotherhood-demand-control-over-assets. In March of that year, the Jordanian government legally recognized the MBS as the country’s sole Brotherhood organization and transferred MBG-held property to the new group.Aida Alami, “Rift deepens within Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood,” Al Jazeera, August 17, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/08/rift-deepens-jordan-muslim-brotherhood-150810121308733.html. Thuneibat was first elected to lead the MBS in 2015.Khetam Malkawi, “New leaders of Brotherhood demand control over assets,” Jordan Times (Amman), March 7, 2015, http://jordantimes.com/new-leaders-of-brotherhood-demand-control-over-assets. He resigned in March 2018, citing health reasons.“Qudah elected Muslim Brotherhood overall leader,” Jordan Times (Amman), March 26, 2018, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/qudah-elected-muslim-brotherhood-overall-leader.

Thuneibat led the MBG for 12 years in the 1990s and early 2000s.“Pragmatists Lead Muslim Brotherhood’s Leadership Race, But Feel Pressure After Hamas’ Victory,” WikiLeaks, February 16, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06AMMAN1177_a.html. As the group’s leader, Thuneibat condemned violence,“Jordan Islamists reject violence,” United Press International, October 26, 2004, http://www.upi.com/Top_News/2004/10/26/Jordan-Islamists-reject-violence/33151098799181/. but also called on the Jordanian government to revive its relations with Hamas after the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood offshoot won Palestinian legislative elections in January 2006.“Jordan Islamists seek new start with Hamas,” United Press International, January 28, 2006, http://www.upi.com/Business_News/Security-Industry/2006/01/28/Jordan-Islamists-seek-new-start-with-Hamas/54011138468993/. Thuneibat condemned Israel’s 2004 assassination of Hamas leader Ahmed Yassin as a “cowardly act which targeted an old and crippled religious man,” and warned that Yassin’s assassination would not “intimidate Palestinians or stop resistance” against Israel.“Jordan warns Israel over Arafat safety,” United Press International, March 22, 2004, http://www.upi.com/Top_News/2004/03/22/Jordan-warns-Israel-over-Arafat-safety/51891079957502/. In January 2006, Thuneibat announced his intention to run for another four-year term,“Pragmatists Lead Muslim Brotherhood’s Leadership Race, But Feel Pressure After Hamas’ Victory,” WikiLeaks, February 16, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06AMMAN1177_a.html. but withdrew from the election two months later.“East Bank Moderate Elected Leader of Muslim Brotherhood,” WikiLeaks, March 7, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06AMMAN1692_a.html.

Thuneibat was among a group of Brotherhood reformists who in 2012 created the National Building Initiative—also known Zamzam—to pressure the Brotherhood to cut ties with the Egyptian Brotherhood and focus on a Jordan-first agenda.Aida Alami, “Rift deepens within Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood,” Al Jazeera, August 17, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/08/rift-deepens-jordan-muslim-brotherhood-150810121308733.html;

Khetam Malkaw, “Muslim Brotherhood Society elects Thneibat as overall leader,” Jordan Times (Amman), January 10, 2016, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/muslim-brotherhood-society-elects-thneibat-overall-leader. In June 2014, Thuneibat began holding so-called “reform” summits, in which he and other reformists called for an overhaul of the Brotherhood and the removal of leader Hammam Saeed. In response, the Brotherhood promised to take disciplinary action against Thuneibat for “inciting insurrection.”Taylor Luck, “Former Brotherhood leader faces disciplinary measures,” Jordan Times (Amman), June 7, 2014, http://jordantimes.com/former-brotherhood-leader-faces-disciplinary-measures. This led to the February 2015 expulsion of Zamzam members from the MBG,Osama Al Sharif, “Jordan takes sides in Islamist rift,” Al-Monitor, May 12, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/05/jordan-government-side-muslim-brotherhood-society-split.html. which Thuneibat and his supporters protested as illegal.Khetam Malkawai, “Brotherhood internal feud puts group at historic crossroads,” Jordan Times (Amman), February 28, 2015, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/brotherhood-internal-feud-puts-group-historic-crossroads. That June, Thuneibat declared that there was “a strong will for change in the movement [among its members],” and that he would “export the uprising from the north to the south.”Taylor Luck, “Brotherhood dissenters declare ‘uprising’ against leadership,” Jordan Times (Amman), June 3, 2014, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/brotherhood-dissenters-declare-uprising%E2%80%99-against-leadership.

After several Middle Eastern countries labeled the Brotherhood a terrorist organization in early 2015, Thuneibat told the Jordan Times that the Jordanian Brotherhood was affected by “any decision taken against” the parent group, and that the Jordanian branch wanted “to avoid being labelled as a terrorist group.”Khetam Malkawai, “Brotherhood internal feud puts group at historic crossroads,” Jordan Times (Amman), February 28, 2015, http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/brotherhood-internal-feud-puts-group-historic-crossroads. That March, Thuneibat and other former MBG members created the MBS in a move to sever ties with the “terrorist group in Egypt,” referring to the Brotherhood’s parent body.Osama Al Sharif, “Jordan takes sides in Islamist rift,” Al-Monitor, May 12, 2015, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2015/05/jordan-government-side-muslim-brotherhood-society-split.html.