Fact:

On April 3, 2017, the day Vladimir Putin was due to visit the city, a suicide bombing was carried out in the St. Petersburg metro, killing 15 people and injuring 64. An al-Qaeda affiliate, Imam Shamil Battalion, claimed responsibility.

Ahmed Luqman Talib is a U.S.-designated, Australian national who is a financial and operational facilitator for al-Qaeda. Talib operates a gemstone business based in Australia. Talib and his company, Talib and Sons, were designated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on October 19, 2020.“Counter Terrorism Designations; Iran-related Designations,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 19, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/recent-actions/20201019; Pranshu Verma, “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Qaeda Financier Who Trades in Gems,” New York Times, October 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/19/us/politics/treasury-sanctions-qaeda-gems.html. On March 29, 2021, Talib was arrested by the Australian police and charged with “one count of preparations for foreign incursions into foreign states for the purpose of engaging in hostile activities.”Toby Crockford, “Australian father-of-eight accused of supporting Syrian Terrorist,” Brisbane Times, March 30, 2021, https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/australian-father-of-eight-accused-of-supporting-syrian-terrorist-20210329-p57f2g.html.

On May 31, 2010, while still a university student at Gold Coast University, Talib joined a flotilla of activists seeking to break an Israeli blockade of Gaza. The flotilla of vessels, which was boarded in international waters about 80 miles from the Israeli coast, was organized in part by a Turkish group called the Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Aid (IHH). The organizers claimed to be delivering humanitarian aid to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. According to the Israeli government, IHH is linked to the terrorist group Hamas and is associated with the U.S.-designated Union of Good charity network. Israeli naval commandos eventually raided and took siege of the flotilla and shot Talib, who survives, along with several others.Pranshu Verma, “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Qaeda Financier Who Trades in Gems,” New York Times, October 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/19/us/politics/treasury-sanctions-qaeda-gems.html; Paul McGeough, “Australian student tells of his flotilla ordeal,” Sydney Morning Herald, June 7, 2010, https://www.smh.com.au/national/australian-student-tells-of-his-flotilla-ordeal-20100606-xnbh.html; Thomas Joscelyn, “Designated al Qaeda facilitator operates gemstone business based in Australia,” Long War Journal, October 19, 2020, https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2020/10/designated-al-qaeda-facilitator-operates-gemstone-business-based-in-australia.php; “Mavi Marmara: Why did Israel stop the Gaza flotilla?,” BBC News, June 27, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/10203726; Jamal Elshayyal, “A decade has passed, but the Mavi Marmara killings I saw still shape me,” Al Jazeera, May 30, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/5/30/a-decade-has-passed-but-the-mavi-marmara-killings-i-saw-still-shape-me.

According to official documents, Talib registered Talib & Sons PTY LTD on February 5, 2019 in Mount Waverly, Australia.“TALIB & SONS PTY LTD ACN 633 227 488,” Australian Securties and Investments Commission, https://connectonline.asic.gov.au/RegistrySearch/faces/landing/panelSearch.jspx?searchText=633227488&searchType=OrgAndBusNm&_adf.ctrl-state=ex5nf0ybi_15. Owned, controlled, and directed by Talib, the company has financial dealings in Brazil, Colombia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Turkey, and the Gulf. By using his company as a cover, Talib was able to move funds internationally for al-Qaeda.“Treasury Designates al-Qa’ida Financial Facilitator,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 19, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1157. According to experts at the Washington Institute, gemstones are easy to move and hold value, which has provided al-Qaeda a way to evade detection from governments and the private sector who have heightened surveillance of formal financial systems to counter the financing of terrorism.Pranshu Verma, “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Qaeda Financier Who Trades in Gems,” New York Times, October 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/19/us/politics/treasury-sanctions-qaeda-gems.html.

On October 19, 2020, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated both Talib for having materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, al-Qaeda. OFAC also designated Talib and Sons.“Treasury Designates al-Qa’ida Financial Facilitator,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 19, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1157.

On March 29, 2021, Talib was arrested in Chambers Flat, in Queensland, Australia. He was charged with one “count of preparations for foreign incursions into foreign states for the purpose of engaging in hostile activities between September 1, 2013 and October 1, 2020.”Toby Crockford, “Australian father-of-eight accused of supporting Syrian Terrorist,” Brisbane Times, March 30, 2021, https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/australian-father-of-eight-accused-of-supporting-syrian-terrorist-20210329-p57f2g.html. His case is currently awaiting a hearing in Brisbane Magistrates Court on June 25, 2021.Toby Crockford, “Australian father-of-eight accused of supporting Syrian Terrorist,” Brisbane Times, March 30, 2021, https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/australian-father-of-eight-accused-of-supporting-syrian-terrorist-20210329-p57f2g.html.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) designated Ahmed Luqman Talib as a Specially Designated National on October 19, 2020.“Treasury Designates al-Qa’ida Financial Facilitator,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, October 19, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm1157.

Djamel Beghal is an Algerian recruiter for al-Qaeda. Beghal was allegedly the mentor to Cherif Kouachi—one of the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo attack in January 2015—and Amedy Coulibaly, the man who killed a policewoman and four shoppers at a kosher supermarket in Paris in January 2015.Michael Birnbaum and Souad Mekhennet, “Djamel Beghal, the charming and chilling mentor of Paris jihadist attackers,” Washington Post, February 6, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/the-charming-and-chilling-mentor-of-the-paris-attackers/2015/02/06/2870f13c-a7dd-11e4-a162-121d06ca77f1_story.html.

An Algerian national, Beghal moved to France in 1987 to continue his studies, and in 1991 he married a French national, becoming a national himself on November 16, 1993.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}. According to media sources, he has been under surveillance by French intelligence agents since the mid-1990s.“France expels alleged mentor of 2015 Paris attackers,” National, July 16, 2018, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/france-expels-alleged-mentor-of-2015-paris-attackers-1.750915. In 1994, Beghal was arrested by French police for suspected membership in a group of armed Algerians. Beghal was released after serving a three month sentence.Chris Hedges, “A NATION CHALLENGED: POLICE WORK; The Inner Workings of a Plot to Blow Up the U.S. Embassy in Paris,” New York Times, October 28, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/28/world/nation-challenged-police-work-inner-workings-plot-blow-up-us-embassy-paris.html. Following his release, Beghal and his family moved to Leicester in the United Kingdom in October 1997.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}.

Beghal became closely associated with a circle of radical clerics in Leicester and frequently attended London’s Finsbury Mosque where he became a close associate of radical imam Abu Hamza al-Masri.Robin De Peyer, “Revealed: Charlie Hebdo suspect mentored by Finsbury Park Mosque lieutenant,” Evening Standard, January 9, 2015, https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/revealed-charlie-hebdo-suspect-was-mentored-by-finsbury-park-mosque-lieutenant-9966920.html. As the head of Finsbury Mosque, Abu Hamza associated remotely with Yemen-based extremist figures, even claiming to serve as the “legal officer” for the al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamic Army of Aden terrorist group.“Designation of 10 Terrorist Financiers Fact Sheet,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, April 19, 2002, https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/po3014.aspx. Abu Hamza was later sentenced in New York for supporting terrorist organizations.Robin De Peyer, “Revealed: Charlie Hebdo suspect mentored by Finsbury Park Mosque lieutenant,” Evening Standard, January 9, 2015, https://www.standard.co.uk/news/world/revealed-charlie-hebdo-suspect-was-mentored-by-finsbury-park-mosque-lieutenant-9966920.html. While travelling to London, Beghal also became close to extremist preacher Abu Qatada, who often sent Beghal throughout Europe to collect donations and distribute recordings of his sermons that commonly espoused violent jihad.Scott Sayare, “The Ultimate Terrorist Factory,” Harper’s Magazine, January 2016, https://harpers.org/archive/2016/01/the-ultimate-terrorist-factory/2/. Given his association with Abu Hamza and Abu Qatada, Beghal came to be seen by U.K. and French intelligence as one of al-Qaeda’s leading recruiters in Europe, and Beghal was reportedly placed on France’s terrorist watch list in 1997.Josh Halliday, Duncan Gardham and Julian Borger, “Mentor of Charlie Hebdo gunmen has been UK-based,” Guardian, January 11, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/11/mentor-charlie-hebdo-gunmen-uk-based-djamel-beghal; “They Had A Plan,” CNN, August 5, 2002, https://edition.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/08/05/time.history/.

Inspired by Abu Qatada’s teachings, Beghal and his family moved to Afghanistan in November 2000 where he allegedly trained with al-Qaeda.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}; David Gauthier-Villars And Stacy Meichtry, “Algerian Terror Convict Links Paris Gunmen,” Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/algerian-terror-convict-links-paris-gunmen-1421119392. While in Afghanistan, Beghal and his family shared a home with Abu Iyadh, a Tunisian once considered the most wanted man in Tunisia. It was also alleged that Beghal spent some time with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founder of ISIS’s predecessor, al-Qaeda in Iraq.Scott Sayare, “The Ultimate Terrorist Factory,” Harper’s Magazine, January 2016, https://harpers.org/archive/2016/01/the-ultimate-terrorist-factory/2/. Months later on July 29, 2001, Beghal was arrested at Abu Dhabi International Airport in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) while attempting to fly with a fake French passport on his way to Europe. Beghal confessed to Emirati authorities that he was persuaded by radical preachers to plot an attack on the American embassy in Paris. While in Emirati detention, Beghal claimed he was tortured and provided false information under duress.“They Had A Plan,” CNN, August 5, 2002, https://edition.cnn.com/2002/ALLPOLITICS/08/05/time.history/.

On September 26, 2001, Beghal was extradited to France from the UAE.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}. After arriving in France, he was indicted for terrorism-related offenses and placed in pre-trial detention. He was suspected of having prepared an attack on the U.S. Embassy in Paris.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}. In 2003, Beghal was convicted in absentia in an Algerian court for membership in a terrorist organization.“Algerian militant suspect expelled by France will be retried: sources,” Reuters, July 17, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-algeria-attacks/algerian-militant-suspect-expelled-by-france-will-be-retried-sources-idUSKBN1K72L3.

On March 15, 2005, the High Court of Paris sentenced Beghal to 10 years in prison for preparing an act of terrorism. Prosecutors argued that Beghal was involved in a network of Islamic militants that spanned across five European countries and who reported to a base in Afghanistan.“France Convicts 6 In Terror Plot,” CBS News, March 15, 2005, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/france-convicts-6-in-terror-plot/. On September 19, 2007, a deportation order to Algeria was issued against Beghal following the completion of his sentence.“L'islamiste Djamel Beghal réclame son expulsion vers l'Algérie,” Le Parisien, June 27, 2017, https://www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/l-islamiste-djamel-beghal-reclame-son-expulsion-vers-l-algerie-27-06-2017-7090224.php. On September 26, 2007, Beghal was stripped of his French nationality.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}.

In 2005, while serving his sentence at the Fleury-Merogis prison in Paris, Beghal allegedly met Coulibaly and Kouachi. Coulibaly and Kouachi allegedly continued to visit Beghal following their release from prison and provided Beghal with food and money.Henri Astier, “Paris attacks: Prisons provide fertile ground for Islamists,” BBC News, February 5, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31129398. On May 31, 2009, Beghal was released from prison and was placed under “judicial surveillance,” a form of house arrest where local police regularly checked on him while also monitoring his phone communications.David Gauthier-Villars And Stacy Meichtry, “Algerian Terror Convict Links Paris Gunmen,” Wall Street Journal, January 13, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/algerian-terror-convict-links-paris-gunmen-1421119392.

Beghal was arrested again on May 19, 2010 as part of a plot to not only escape France but also free Smain Ait Ali Belkacem from prison. Belkacem was an Algerian who was involved in the 1995 Paris bomb attacks which killed eight people.“Djamel Beghal and his alleged accomplices still questioned,” L’Express, May 19, 2010, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/djamel-beghal-et-ses-presumes-complices-toujours-interroges_893257.html. On May 22, 2010, the High Court of Paris indicted Beghal for acts of directing and organizing a criminal association with a view to prepare acts of terrorism while in a state of legal recidivism. Upon investigation of his living quarters, French police found a clipping about rocket-propelled grenades, maps of Afghanistan and Pakistan, printouts on suicide attacks, and music featuring titles such as “I, Terrorist,” and “Blow Them Up.”Michael Birnbaum and Souad Mekhennet, “Djamel Beghal, the charming and chilling mentor of Paris jihadist attackers,” Washington Post, February 6, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/the-charming-and-chilling-mentor-of-the-paris-attackers/2015/02/06/2870f13c-a7dd-11e4-a162-121d06ca77f1_story.html. He was remanded in custody.“BEGHAL c. France,” European Court of Human Rights, September 6, 2011, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22languageisocode%22:[%22FRE%22],%22appno%22:[%2227778/09%22],%22documentcollectionid2%22:[%22ADMISSIBILITYCOM%22],%22itemid%22:[%22001-106364%22]}.

On July 16, 2018, Beghal was released from Venzin-le-Coquet prison and was put on a flight to Algiers.“Expelled from France, jihadist attacker 'mentor' Beghal to be retried in Algeria,” France 24, July 17, 2018, https://www.france24.com/en/20180717-france-algeria-terrorism-beghal-expelled-jihadist-attacks-mentor-retrial-charlie-hebdo. On July 17, 2018, Algerian authorities stated that they would retry Beghal who will face up to 20 years imprisonment for membership in a terrorist organization.“Algerian militant suspect expelled by France will be retried: sources,” Reuters, July 17, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-algeria-attacks/algerian-militant-suspect-expelled-by-france-will-be-retried-sources-idUSKBN1K72L3; “Expelled from France, jihadist attacker 'mentor' Beghal to be retried in Algeria,” France 24, July 17, 2018, https://www.france24.com/en/20180717-france-algeria-terrorism-beghal-expelled-jihadist-attacks-mentor-retrial-charlie-hebdo. As of September 2020, no new developments have been reported on Beghal’s activities or his trial in Algeria.

Mohamed Belhoucine is a French jihadist who allegedly was the mentor to Amedy Coulibaly, the pro-ISIS terrorist who carried out the January 9, 2015, kosher supermarket attack in Paris.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804. Additionally, he has been considered the main facilitator of Coulibaly’s spouse Hayat Boumedienne’s flight to Syria.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html. On December 16, 2020, Belhoucine and 13 others were convicted in France for aiding the 2015 attacks.Valentin Bontemps and Anne-Sophie Lasserre. “French Court Jails 13 Accomplices Over Charlie Hebdo Attack,” International Business Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.ibtimes.com/french-court-jails-13-accomplices-over-charlie-hebdo-attack-3103065.

Belhoucine was a former engineering student at the Albi School of Mines (Tarn). However, he did not complete his studies and dropped out after two years in 2009. In 2010, Belhoucine was arrested by French authorities for his role in the “Afghan sector,” which was a group that allegedly facilitated the travel of jihadists to Afghanistan and Pakistan. On July 11, 2014, the Paris Criminal Court sentenced Belhoucine to two years in prison, but his sentence was suspended after one year.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html.

Reports allege that Belhoucine met Coulibaly sometime in 2014 and began to provide Coulibaly with jihadist literature and facilitated Coulibaly’s online communication with jihadist sponsors.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html. On January 9, 2015, Coulibaly opened fire on a Paris kosher supermarket, ultimately killing four people. Coulibaly was subsequently killed in a shootout with police later that day.Ricky Ben-David, “4 dead as French forces storm kosher supermarket, kill gunman; Charlie Hebdo terrorist brothers also killed,” Times of Israel, January 10, 2015, http://www.timesofisrael.com/terror-onslaught-in-paris/. It was reported that Belhoucine had flown into Istanbul from Madrid a week earlier on January 2, 2015. Six days later, he evaded Turkish authorities and reportedly entered Syria with his brother, Mehdi, and Coulibaly’s widow, Hayat Boumedienne.“Paris Gunman ‘was with five others in Madrid’,” The Local, January 11, 2015, https://www.thelocal.es/20150117/paris-gunman-coulibaly-was-with-five-others-in-madrid.

Following the kosher supermarket attack, French authorities inspected Coulibaly’s apartment and discovered Belhoucine’s writings, which included a letter of allegiance to ISIS.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html. Additionally, French authorities discovered that Belhoucine had provided Coulibaly with two encrypted messaging accounts, which Coulibaly used to communicate with the sponsor of the two attacks he later carried out. The sponsor was never identified, but it is alleged he was based in Turkey and operated an account with the name [email protected].Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html.

Unconfirmed reports claimed that Belhoucine had been killed in Syria in 2016 following a series of drone strikes carried out by coalition forces in the region.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804; Sarah Chemla, “France’s ‘most-wanted woman’ absent from 2015 Paris attacks trial,” Jerusalem Post, September 2, 2020, https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/antisemitism/frances-most-wanted-woman-absent-from-2015-paris-attacks-trial-640783.

On September 2, 2020, France’s anti-terrorism prosecutors began the trials of 14 people accused of aiding the 2015 terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo and other Paris targets, including the kosher supermarket attack.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804. Belhoucine was one of three suspects tried in absentia along with his brother Mehdi Belhoucine and Hayat Boumedienne.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804. According to prosecutors, Belhoucine helped Coulibaly prepare his attack, connected him with ISIS militants, and helped him prepare the video in which he pledged allegiance to ISIS.“Factbox: The Charlie Hebdo attackers and their alleged accomplices,” Reuters, September 1, 2020, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-france-charliehebdo-suspects-factbox-idUKKBN25S6B3. All 14 defendants were found guilty on December 16, 2020. Belhoucine received a life sentence, though his whereabouts remain unknown. His brother, Mehdi Belhoucine, was also found guilty but was not sentenced because of what the court claimed to be overwhelming evidence that he was dead.Valentin Bontemps and Anne-Sophie Lasserre. “French Court Jails 13 Accomplices Over Charlie Hebdo Attack,” International Business Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.ibtimes.com/french-court-jails-13-accomplices-over-charlie-hebdo-attack-3103065; Roger Cohen, “French Court Finds 14 People Guilty of Aiding Charlie Hebdo and Anti-Semitic Attacks,” New York Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/16/world/europe/charlie-hebdo-trial-guilty.html.

Mehdi Belhoucine is a French jihadist who allegedly was linked to Amedy Coulibaly, the pro-ISIS terrorist who carried out the January 9, 2015 kosher supermarket attack in Paris.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804. According to reports, Belhoucine, along with his brother, Mohamed, facilitated the travel of Coulibaly’s partner and accomplice, Hayat Boumedienne, into Syria.Noémie Bisserbe, Benoît Faucon And Stacy Meichtry, “Underground Terror Network Said to Benefit Would-Be Jihadists in Europe,’ Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/underground-terror-network-said-to-benefit-would-be-jihadists-in-europe-1422577767. On December 16, 2020, Behoucine and 13 others were convicted in France of aiding the 2015 attacks.Valentin Bontemps and Anne-Sophie Lasserre. “French Court Jails 13 Accomplices Over Charlie Hebdo Attack,” International Business Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.ibtimes.com/french-court-jails-13-accomplices-over-charlie-hebdo-attack-3103065.

Belhoucine did not have a criminal record, but was previously questioned and released by French authorities in July 2014 when his brother was on trial for his participation in the “Afghan Sector”—a group that facilitated the travel of foreigners to wage jihad in Afghanistan and Pakistan.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html.

Reports allege that Belhoucine’s brother, Mohamed, met Coulibaly sometime in 2014 and began to provide Coulibaly with jihadist literature and facilitated Coulibaly’s online communication with jihadist sponsors.Boris Thiolay, “Jihadists at bac + 5 level,” L’Express, October 23, 2018, https://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/enquete/djihadistes-niveau-bac-5_2039581.html. On January 9, 2015, Coulibaly opened fire on a Paris kosher supermarket, ultimately killing four people. Coulibaly was later killed in a shootout with police later that day.Ricky Ben-David, “4 dead as French forces storm kosher supermarket,kill gunman; Charlie Hebdo terrorist brothers also killed,” Times of Israel, January 10, 2015, http://www.timesofisrael.com/terror-onslaught-in-paris/.

It was reported that Belhoucine had flown into Istanbul from Madrid a week earlier on January 2, 2015. Six days later, he evaded Turkish authorities and entered Syria with his brother, Mohamed, and Coulibaly’s widow, Boumedienne.“Paris Gunman ‘was with five others in Madrid’,” The Local, January 11, 2015, https://www.thelocal.es/20150117/paris-gunman-coulibaly-was-with-five-others-in-madrid. Once in Syria, Belhoucine reportedly served as Boumedienne’s security detail.Noémie Bisserbe, Benoît Faucon And Stacy Meichtry, “Underground Terror Network Said to Benefit Would-Be Jihadists in Europe,’ Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/underground-terror-network-said-to-benefit-would-be-jihadists-in-europe-1422577767.

Unconfirmed reports claimed that Belhoucine had been killed in Syria in 2016 following a series of drone strikes carried out by coalition forces in the region.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804; Sarah Chemla, “France’s ‘most-wanted woman’ absent from 2015 Paris attacks trial,” Jerusalem Post, September 2, 2020, https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/antisemitism/frances-most-wanted-woman-absent-from-2015-paris-attacks-trial-640783.

On September 2, 2020, France’s anti-terrorism prosecutors began the trials of 14 people accused of aiding the 2015 terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo and other Paris targets, including the kosher supermarket attack.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804; Melissa Bell, Eva Tapiero, Pierre Bairin, and Zamira Rahim, “Charlie Hebdo terror trial begins in Paris, five years after deadly attacks,” CNN, September 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/02/europe/charlie-hebdo-trial-paris-attacks-intl/index.html. Belhoucine was one of three suspects tried in absentia along with his brother Mohamed Belhoucine and Hayat Boumedienne.“France Pushes Back Charlie Hebdo Attack Trial To September,” Barron’s, March 31, 2020, https://www.barrons.com/news/france-pushes-back-charlie-hebdo-attack-trial-to-september-01585657804. All 14 defendants were found guilty on December 16, 2020. Belhoucine was not sentenced because of what the court claimed to be overwhelming evidence that he was dead.Valentin Bontemps and Anne-Sophie Lasserre. “French Court Jails 13 Accomplices Over Charlie Hebdo Attack,” International Business Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.ibtimes.com/french-court-jails-13-accomplices-over-charlie-hebdo-attack-3103065; Roger Cohen, “French Court Finds 14 People Guilty of Aiding Charlie Hebdo and Anti-Semitic Attacks,” New York Times, December 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/16/world/europe/charlie-hebdo-trial-guilty.html.

Mohamad Ameen is a U.S.-designated Maldivian recruiter and leader for ISIS’s Wilayat Khorasan. Ameen has allegedly facilitated the recruitment of many foreign fighters from the Maldives to Syria and Afghanistan. Additionally, Ameen is allegedly connected to the 2007 Sultan Park bombing in Malé—the first terror attack to occur in the Maldives.“Treasury Targets Wide Range of Terrorists and Their Supporters Using Enhanced Counterterrorism Sanctions Authorities,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 10, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm772. Ameen is the first Maldivian to be designated as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist by the United States and is also the first person to be charged under the Maldives’ Anti-Terrorism Laws.Ahmedulla Abdul Hadi, “2 counts of terrorism made against local terror recruiter,” Sun (Maldives), December 6, 2019, https://en.sun.mv/56988.

Maldivian authorities sought to arrest Ameen in connection to the September 29, 2007 bombing in Sultan Park, Malé. The attack resulted in the injury of 12 foreign nationals.Ajay Makan, “Bomb blast wounds 12 tourists in Maldives capital,” Reuters, September 29, 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-maldives-explosion/bomb-blast-wounds-12-tourists-in-maldives-capital-idUSCOL8415420070929. However, Ameen managed to flee the country before an arrest could be made.“Police arrest Maldivian on America's OFAC terrorist list,” Edition, October 24, 2019, https://edition.mv/news/13112. Following his escape, INTERPOL issued a Red Notice for information about Ameen and other suspects connected to the bombing.“Sultan Park bombing suspect arrested in Sri Lanka,” Sun (Maldives), October 15, 2011, https://en.sun.mv/507.

Ameen was arrested by Sri Lankan police on October 15, 2011, when he tried to enter Sri Lanka using a forged passport. At the time of arrest, he had both a Maldivian and Pakistani passport in his possession.Shahudha Mohamed, “Police arrest Maldivian on America's OFAC terrorist list,” The Edition, October 24, 2019, https://edition.mv/news/13112. A few months later, Ameen was transferred to Maldivian custody where a local court ordered his release in May 2012. His release was granted on the condition that “he would neither get involved in any further terrorist activities nor leave the country.”Sathiya Moorthy, “Maldives: Designation brings US terror war closer?” Observer Research Foundation, September 13, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/maldives-designation-us-terror-war-closer-55422/.

On September 10, 2019, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) listed Ameen as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist.“Treasury Targets Wide Range of Terrorists and Their Supporters Using Enhanced Counterterrorism Sanctions Authorities,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 10, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm772. Ameen allegedly assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support to ISIS and ISIS’s Wilayat Khorasan. ISIS officially formed Wilayat Khorasan in January 2015 after jihadists in Afghanistan and Pakistan pledged allegiance to ISIS in November 2014.“Islamic State moves in on al-Qaeda turf,” BBC News, June 25, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-31064300. Wilayat Khorasan is based in Afghanistan’s Nangarhar region and its ranks include former members of the Pakistan Taliban, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, and foreign fighters.“U.S. General Says Taliban Controls 10 Percent Of Afghanistan,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, September 23, 2016, https://www.rferl.org/a/28009576.html.; Merhat Sharipzhan, “IMU Declares It Is Now Part Of The Islamic State,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, August 6, 2015, http://www.rferl.org/content/imu-islamic-state/27174567.html.

As recently as April 2019, Ameen continued to lead ISIS recruitment sessions across the Maldives. Ameen and his subordinates provided up to as many as 10 weekly recruitment sessions across Malé under the guise of Islamic classes. Furthermore, Ameen and his subordinates recruited heavily among Maldivian criminal gangs. The recruits were originally sent to Syria but were later redirected to Afghanistan.“Treasury Targets Wide Range of Terrorists and Their Supporters Using Enhanced Counterterrorism Sanctions Authorities,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 10, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm772.

According to OFAC, Ameen allegedly facilitated the travel of Maldivians to Afghanistan, where he promised recruits that they would join the digital media ranks of ISIS-K. Upon arrival, the recruits would be responsible for translating digital material for him and would receive $700 a month as compensation.“Treasury Targets Wide Range of Terrorists and Their Supporters Using Enhanced Counterterrorism Sanctions Authorities,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, September 10, 2019, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm772.

On October 24, 2019, the Maldives Police Service arrested Ameen over allegations of spreading extremist ideologies in the Indian Ocean archipelago as well as recruiting and directing terrorist fighters abroad.“Maldives police arrest recruiter for Daesh,” Arab News, October 24, 2019, https://www.arabnews.com/node/1573736/world. Additionally, police alleged that Ameen had maintained financial and technological links to senior members of unnamed terrorist groups.Ahmedulla Abdul Hadi, “2 counts of terrorism made against local terror recruiter,” Sun (Maldives), December 6, 2019, https://en.sun.mv/56988. On December 5, 2019, the Maldivian Prosecutor General’s Office submitted two charges of terrorism against Ameen to the Criminal Court. The charges included being a member of a terrorist organization and planning an act of terrorism.Ahmedulla Abdul Hadi, “2 counts of terrorism made against local terror recruiter,” Sun (Maldives), December 6, 2019, https://en.sun.mv/56988.

On February 3, 2021, the Maldives Criminal Court ordered Ameen to be transferred from prison to house arrest. Reportedly, the transfer occurred because the prison was unable to offer him adequate medical treatment and did not give him the opportunity to exercise outside of his cell. The house arrest agreement stipulated that Ameen cannot leave his home or commit another terrorist offense.“First Maldivian on USA's OFAC Terrorist List Mohamed Ameen Allowed House Arrest,” India Blooms News Service, February 9, 2021, https://www.indiablooms.com/world-details/F/27940/first-maldivian-on-usa-s-ofac-terrorist-list-mohamed-ameen-allowed-house-arrest.html; ANI, “First Maldivian on OFAC Terrorist List Allowed House Arrest,” Business World, February 8, 2021, http://www.businessworld.in/article/First-Maldivian-on-OFAC-terrorist-list-allowed-house-arrest/08-02-2021-375293/.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Mohamad Ameen as a Specially Designated National on September 10, 2019.“Executive Order Amending Counter Terrorism Sanctions Authorities; Counter Terrorism Designations and Designations Updates; Iran-related Designation; Syria Designations Updates,” U.S. Department of Treasury, September 10, 2019, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20190910.aspx.

Following the Sultan Park bombing in September 2007, INTERPOL issued a Red Notice for information about Mohamad Ameen and other suspects connected to the Sultan Park bombing.“Sultan Park bombing suspect arrested in Sri Lanka,” Sun (Maldives), October 15, 2011, https://en.sun.mv/507.

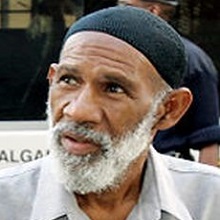

Kareem Ibrahim was a designated terrorist by the government of Trinidad and Tobago. He was also a former imam who provided religious instruction and operational support to a group plotting to commit a terrorist attack at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York in June 2007.“Consolidated List of Court Orders Issued by the High Court of Justice of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Under Section 22B (3) Anti-Terrorism Act, CH. 12:07,” Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, December 3, 2015, https://www.fiu.gov.tt/wp-content/uploads/03-Dec-15-TT-Consolidated-List-of-High-Court-Orders.pdf; “Kareem Ibrahim Sentenced to Life in Prison for Conspiring to Commit Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, January 13, 2012, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2012/kareem-ibrahim-sentenced-to-life-in-prison-for-conspiring-to-commit-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport. On January 19, 2016, Ibrahim died of heart failure at the U.S. Medical Center in Springfield, Missouri.John Marzulli, “Terrorist who plotted blowing up JFK fuel tanks dies in federal prison,” New York Daily News, February 5, 2016, https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/terrorist-plotted-blowing-jfk-fuel-tanks-dies-article-1.2522242.

On June 2, 2007, U.S. federal authorities uncovered a plot by a suspected terrorist cell to blow up John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Ibrahim was one of four suspects. The suspects targeted the airport because it was a symbol that would put “the whole country in mourning.”“U.S.: ‘Unthinkable’ terror devastation prevented,” NBC News, June 3, 2007, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/18999503/ns/us_news-security/t/us-unthinkable-terror-devastation-prevented/#.Xo9Ybf1Kipq. Ibrahim and several co-conspirators sought to explode fuel tanks and fuel pipelines under the airport in order to cause extensive damage to the airport, the New York economy, and to also result in a large number of casualties.William K. Rashbaum, “4 Men Charged in Plot to Bomb Kennedy Airport,” New York Times, June 2, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/02/nyregion/02cnd-plot.html.

Trinidadian authorities arrested Ibrahim on June 3, 2007, and charged with conspiring to commit acts of terrorism in the United States. On June 25, 2008, the Port-of-Spain High Court ordered Ibrahim to be extradited to face charges in New York.Prior Beharry, “Suspects in Kennedy Plot Extradited From Trinidad,” New York Times, June 25, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/25/nyregion/25extradite.html.

Law enforcement officials who investigated the case claimed that the plot was only in a preliminary phase and that the suspects had not yet acquired the funding or necessary explosives to carry out the attack. Authorities claimed that the suspects had “fundamentalist Islamic beliefs of a violent nature” and that the men were motivated by a hatred for the United States and Israel.Cara Buckley and William K. Rashbaum, “4 Men Accused of Plot to Blow Up Kennedy Airport Terminals and Fuel Lines,” New York Times, June 3, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/03/nyregion/03plot.html. Authorities became aware of the plot through a convicted drug trafficker who agreed to act as an informant to the U.S. government in exchange for a more lenient sentence and a stipend.Colin Moynihan, “15-Year Sentence for Conspirator in Airport Plot,” New York Times, January 13, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/14/nyregion/14plot.html.

Prior to his involvement in the plot, Ibrahim was an imam and a leading figure in the Shiite community in Trinidad and Tobago. It is alleged that the mastermind behind the plot, Russell Defreitas, recruited Ibrahim in 2006.“Imam from Trinidad Convicted of Conspiracy to Launch Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 26, 2011, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2011/imam-from-trinidad-convicted-of-conspiracy-to-launch-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport. In May of 2007, Defreitas, a former cargo handler at JFK Airport, provided Ibrahim with video surveillance and satellite imagery of possible locations for an attack. According to reports, Ibrahim allegedly had connections with militant leaders in Iran who could provide assistance in carrying out the plot. Among those revolutionary leaders was Mohsen Rabbani, the former cultural attaché indicted for orchestrating the 1994 bombing of a Jewish cultural center in Argentina.“Imam from Trinidad Convicted of Conspiracy to Launch Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 26, 2011, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2011/imam-from-trinidad-convicted-of-conspiracy-to-launch-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport. Additionally, Ibrahim advised the plotters to recruit suicide operatives for the attack.“Kareem Ibrahim Sentenced to Life in Prison for Conspiring to Commit Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, January 13, 2012, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2012/kareem-ibrahim-sentenced-to-life-in-prison-for-conspiring-to-commit-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport. It is alleged that the men had ties to Jamaat al-Muslimeen, an Islamist group in Trinidad and Tobago who attempted to carry out a coup against the government in Trinidad and Tobago in 1990. However, Yasin Abu Bakr, the leader of Jamaat al-Muslimeen, denies any association with the plot.Cara Buckley and William K. Rashbaum, “4 Men Accused of Plot to Blow Up Kennedy Airport Terminals and Fuel Lines,” New York Times, June 3, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/03/nyregion/03plot.html.

On June 25, 2008, Ibrahim appeared at the Eastern District Court in New York and pleaded not guilty.“3 plead not guilty in plot to bomb JFK,” CNN, June 25, 2008, https://www.cnn.com/2008/CRIME/06/25/terror.plot/index.html. He was held in custody and did not apply for bail.Christine Kearney, “N.Y. airport plot suspects extradited, plead innocent,” Reuters, June 25, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-plot-airport/n-y-airport-plot-suspects-extradited-plead-innocent-idUSN2549835520080626. According to reports, Ibrahim suffered a variety of health ailments and was confined to prison hospitals throughout the extent of his hearings and trials, resulting in Ibrahim being tried separately from his co-conspirators.John Marzulli, “Accused JFK terror plotter Kareem Ibrahim starving for a death wish?,” New York Daily News, November 16, 2008, https://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/accused-jfk-terror-plotter-kareem-ibrahim-starving-death-article-1.338961.; A.G. Sulzberger, “3 Years Later, Trial to Start in J.F.K. Bomb Plot,” New York Times, June 29, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/30/nyregion/30terror.html?searchResultPosition=4. On May 26, 2011, Ibrahim was convicted by the Eastern District of New York court on multiple charges of conspiring to attack mass public transportation systems and facilities.“Imam from Trinidad Convicted of Conspiracy to Launch Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 26, 2011, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2011/imam-from-trinidad-convicted-of-conspiracy-to-launch-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport. On January 13, 2012, Ibrahim was sentenced to life in prison.“Kareem Ibrahim Sentenced to Life in Prison for Conspiring to Commit Terrorist Attack at JFK Airport,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, January 13, 2012, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/newyork/press-releases/2012/kareem-ibrahim-sentenced-to-life-in-prison-for-conspiring-to-commit-terrorist-attack-at-jfk-airport.

On December 3, 2015, the Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago listed Ibrahim as a designated terrorist and issued an order to freeze all of his assets.“Consolidated List of Court Orders Issued by the High Court of Justice of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Under Section 22B (3) Anti-Terrorism Act, CH. 12:07,” Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, December 3, 2015, https://www.fiu.gov.tt/wp-content/uploads/03-Dec-15-TT-Consolidated-List-of-High-Court-Orders.pdf.

On January 19, 2016, Ibrahim died of heart failure at the U.S. Medical Center in Springfield, Missouri.John Marzulli, “Terrorist who plotted blowing up JFK fuel tanks dies in federal prison,” New York Daily News, February 5, 2016, https://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/terrorist-plotted-blowing-jfk-fuel-tanks-dies-article-1.2522242.

The government of Trinidad and Tobago lists Kareem Ibrahim as a designated terrorist and issues an order to freeze all of his assets.“Consolidated List of Court Orders Issued by the High Court of Justice of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago Under Section 22B (3) Anti-Terrorism Act, CH. 12:07,” Government of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, December 3, 2015, https://www.fiu.gov.tt/wp-content/uploads/03-Dec-15-TT-Consolidated-List-of-High-Court-Orders.pdf.

Aafia Siddiqui is a Pakistani citizen and U.S.-educated neuroscientist who allegedly belonged to an al-Qaeda cell in Pakistan. She is currently serving an 86-year sentence in U.S. federal prison for assaulting U.S. federal agents, employees, and nationals during a 2008 interrogation in Afghanistan.“Aafia Siddiqui Sentenced in Manhattan Federal Court to 86 Years for Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Crimes,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 23, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/September10/siddiquiaafiasentencingpr.pdf; David Ingram, “Pakistani woman embraced by Islamic State seeks to drop U.S. legal appeal,” Reuters, September 18, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-courts-siddiqui-idUSKBN0HD0DR20140918. The Pakistani government has lobbied for her release while al-Qaeda and other extremist groups have repeatedly demanded Siddiqui’s release in exchange for hostages.Dean Nelson and Raf Sanchez, “‘Free British hostages’ say family of Isil poster girl,” Telegraph (London), September 19, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iraq/11109612/Free-British-hostages-say-family-of-Isil-poster-girl.html; Holly McKay, “Pakistani PM opens door to prisoner swap with US to free ‘hero’ doctor who helped track bin Laden,” Fox News, July 23, 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/pakistan-pm-prisoner-doctor-laden.

Born in Pakistan in 1972, Siddiqui moved to the United States in 1990 on a student visa. She attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and then Brandeis University, earning a PhD in neuroscience.Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida. Siddiqui’s radicalization began while she was studying in Massachusetts, which coincided with the Bosnian civil war. During her sophomore year, Siddiqui won a $5,000 grant for a research project on “Islamization in Pakistan and its Effects on Women.” She briefly returned to Pakistan to conduct research. In 1993, Siddiqui volunteered with the Muslim Students Association (MSA) to fundraise for the Al-Kifah Refugee Center, which was later revealed to be a charitable front for al-Qaeda with links to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Al-Kifa’s messaging blamed the United States for the suffering of Bosnian Muslims. Siddiqui began to encourage other students to travel abroad to take up arms on behalf of Bosnian Muslims. She took shooting lessons at a local gun club and encouraged other MSA members to join her. Other students recalled Siddiqui criticizing the United States and the FBI during a visit.Sally Jacobs, “The woman ISIS wanted back,” Boston Globe, December 28, 2014, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/12/27/aafia/T1A0evotz4pbEf5U3vfLKJ/story.html.

In 1995, Siddiqui married Mohammed Amjad Khan, a doctor from Karachi, Pakistan. The couple lived in Boston while Khan finished her schooling. Khan later told the Boston Globe that he stopped bringing guests to the couple’s home because Siddiqui would try to convert them to Islam. The couple attended the Islamic Society of Boston’s Prospect Street mosque, whose attendees later included Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev. Siddiqui increasingly blamed the United States for the suffering of Muslims around the world. Khan told the Globe that Siddiqui began watching Islamist propaganda videos online and training to go overseas. By the time Siddiqui finished her doctoral dissertation in 2001, she had become focused on “jihad against America,” according to Khan.Sally Jacobs, “The woman ISIS wanted back,” Boston Globe, December 28, 2014, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/12/27/aafia/T1A0evotz4pbEf5U3vfLKJ/story.html. In May 2002, FBI agents questioned the couple about online purchases of night vision goggles, body armor, and military books.Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida.

Khan and Siddiqui moved to Pakistan in June 2002. They divorced that August before the birth of their third child.Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida; “Aafia Siddiqui Indicted for Attempting to Kill United States Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 2, 2008, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2008/September/08-nsd-765.html. Siddiqui then allegedly became involved with an al-Qaeda cell in Karachi led by 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) that was planning attacks on the United States, Pakistan, and Great Britain. That December, Siddiqui returned to the United States for 10 days under the pretense of applying for academic positions, leaving her three children in Pakistan with her mother. Siddiqui opened a U.S. post office box under the name of al-Qaeda agent Majid Khan, another member of Siddiqui’s cell.Gordon Rayner, Bill Gardner, Tom Whitehead, and Ben Farmer, “Alan Henning charity campaigned for release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda’ Aafia Siddiqui,” Telegraph (London), September 16, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11099969/Alan-Henning-charity-campaigned-for-release-of-Lady-al-Qaeda-Aafia-Siddiqui.html; Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida. Khan was arrested in Pakistan in 2003 and named Siddiqui as an accomplice during subsequent CIA interrogations.Jason Ryan, “Alleged Maryland Al Qaeda Operative for Second Wave 9/11 Attacks Pleads Guilty,” February 29, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/International/alleged-maryland-al-qaeda-operative-wave-911-attacks/story?id=15814121.

In early 2003 in Pakistan, Siddiqui married Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew of KSM.“Aafia Siddiqui Forensic Psychological Evaluation,” IntelWire, accessed March 4, 2020,, 3, http://intelfiles.egoplex.com/2009-07-01-Siddiqui-psych-report.pdf; Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida. According to interrogations of multiple prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, Siddiqui’s cell planned to attack U.S. economic targets using explosives smuggled into the country disguised as clothing imports. According to an FBI-Joint Terrorism Taskforce report on co-conspirator and Guantanamo inmate Saifullah Paracha, Siddiqui responsible for renting houses and providing administrative support for the operation.“The Guantanamo Docket: Saifullah Paracha: JTF-GTMO Assessment,” New York Times, accessed March 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/guantanamo/detainees/1094-saifullah-paracha During interrogations following his 2003 capture, KSM named Siddiqui as an al-Qaeda courier.Gordon Rayner, Bill Gardner, Tom Whitehead, and Ben Farmer, “Alan Henning charity campaigned for release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda’ Aafia Siddiqui,” Telegraph (London), September 16, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11099969/Alan-Henning-charity-campaigned-for-release-of-Lady-al-Qaeda-Aafia-Siddiqui.html.

Siddiqui reportedly disappeared in March 2003 after the FBI issued a global alert for her and her ex-husband Khan for questioning about possible contacts with Osama bin Laden. Siddiqui was last seen entering a taxi with her three children in Karachi.Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida; Associated Press, “Pakistani Woman Wanted by FBI,” Plainview Daily Herald, April 22, 2003, https://www.myplainview.com/news/article/Pakistani-Woman-Wanted-by-FBI-9118686.php. According to Khan, Siddiqui was hiding in Pakistan.Salman Masood and Carlotta Gall, “U.S. Sees a Terror Threat; Pakistanis See a Heroine,” New York Times, March 5, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/06/world/asia/06pstan.html. Shortly after, Baluchi was captured and transferred to the U.S. facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.“Aafia Siddiqui Forensic Psychological Evaluation,” IntelWire, accessed March 4, 2020, 3, http://intelfiles.egoplex.com/2009-07-01-Siddiqui-psych-report.pdf; Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida. In May 2004, the FBI named Siddiqui as one of its seven most wanted al-Qaeda fugitives.Sally Jacobs, “The woman ISIS wanted back,” Boston Globe, December 28, 2014, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/12/27/aafia/T1A0evotz4pbEf5U3vfLKJ/story.html. But Siddiqui’s family alleges that Pakistani intelligence turned Siddiqui over to U.S. authorities in 2003.Salman Masood and Carlotta Gall, “U.S. Sees a Terror Threat; Pakistanis See a Heroine,” New York Times, March 5, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/06/world/asia/06pstan.html. Siddiqui and various advocacy organizations claim U.S. agents kidnapped and imprisoned Siddiqui at a secret U.S. prison at Afghanistan’s Bagram airfield. Siddiqui claims that she was interrogated, tortured, and held in solitary confinement there for five years.Juliane von Mittelstaedt, “America’s Most Wanted,” Spiegel Online, November 27, 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/america-s-most-wanted-the-most-dangerous-woman-in-the-world-a-593195.html. In April 2003, NBC News reported that Siddiqui had been arrested in Pakistan,Juliane von Mittelstaedt, “America’s Most Wanted,” Spiegel Online, November 27, 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/america-s-most-wanted-the-most-dangerous-woman-in-the-world-a-593195.html; Aafia Movement, “NBC News April 2003 arrest of Dr. Aafia,” DailyMotion video, January 30, 2013, accessed March 4, 2020, http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xx5q4d_nbc-news-april-2003-arrest-of-dr-aafia_news. but no other information on her capture could be determined. Other prisoners from Bagram reported a female inmate in solitary confinement whose screams could be heard throughout the facility. The inmates nicknamed the woman the “gray lady of Bagram.”Juliane von Mittelstaedt, “America’s Most Wanted,” Spiegel Online, November 27, 2008, http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/america-s-most-wanted-the-most-dangerous-woman-in-the-world-a-593195.html; Suzanne Goldenberg and Saeed Shah, “Mystery of ‘ghost of Bagram’ – victim of torture or captured in a shootout?” Guardian (London), August 5, 2008, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/aug/06/pakistan.afghanistan. U.S. officials deny Siddiqui’s account, though it appears to be widely accepted in Pakistan where Siddiqui is heralded as a hero.Salman Masood and Carlotta Gall, “U.S. Sees a Terror Threat; Pakistanis See a Heroine,” New York Times, March 5, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/06/world/asia/06pstan.html.

Siddiqui resurfaced in January 2008 when she allegedly sought the help of her uncle, S.H. Faruqi, in reaching out to the Taliban, according to Faruqi.Salman Masood and Carlotta Gall, “U.S. Sees a Terror Threat; Pakistanis See a Heroine,” New York Times, March 5, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/06/world/asia/06pstan.html. On July 17, 2008, Afghan authorities arrested and detained Siddiqui and her then-11-year-old son outside the Ghazni province governor’s compound. Siddiqui was carrying sodium cyanide, documents detailing the assembly of explosives, and descriptions of various U.S. landmarks, including the Statue of Liberty and Empire State Building.“Aafia Siddiqui Arrested for Attempting to Kill United States Officers in Afghanistan,” U.S. Department of Justice, August 4, 2008, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2008/August/08-nsd-687.html; “Aafia Siddiqui Indicted for Attempting to Kill United States Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 2, 2008, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2008/September/08-nsd-765.html; Shane Harris, “Lady al Qaeda: The World’s Most Wanted Woman,” Foreign Policy, August 26, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/08/26/lady-al-qaeda-the-worlds-most-wanted-woman/; “US jails Pakistani scientist for 86 years,” BBC News, September 23, 2010, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-11401865. The following day, a group of U.S. Army officers, FBI agents, and Army-contracted interpreters sought to interrogate Siddiqui at an Afghan police compound. According to the charges against Siddiqui, during the interrogation, Siddiqui grabbed the M-4 rifle of a U.S. Army officer and shot at another Army officer. Siddiqui then assaulted an Army interpreter who tried to wrestle the rifle away, and assaulted the FBI agents and Army officers who tried to subdue her.“Aafia Siddiqui Sentenced in Manhattan Federal Court to 86 Years for Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Crimes,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 23, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/September10/siddiquiaafiasentencingpr.pdf; Basil Katz, “Pakistani scientist loses appeal on shooting conviction,” Reuters, November 5, 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-security-appeals-idUSBRE8A41L120121105. No U.S. officials were injured, but Siddiqui was shot in the stomach during the struggle and underwent emergency surgery at Afghanistan’s Bagram airfield.Declan Walsh, “The mystery of Dr Aafia Siddiqui,” Guardian (London), November 23, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/nov/24/aafia-siddiqui-al-qaida. Siddiqui was transferred to the United States the following month.“Aafia Siddiqui Sentenced in Manhattan Federal Court to 86 Years for Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Crimes,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 23, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/September10/siddiquiaafiasentencingpr.pdf.

In September 2008, the U.S. government indicted Siddiqui on charges of attempting to kill U.S. nationals outside the United States; attempting to kill U.S. officers and employees; armed assault of U.S. officers and employees; using and carrying a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence; and three counts of assault of U.S. officers and employees.“Aafia Siddiqui Indicted for Attempting to Kill United States Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Charges,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 2, 2008, https://www.justice.gov/archive/opa/pr/2008/September/08-nsd-765.html. On February 3, 2010, Following a two-week trial in New York City, Siddiqui was convicted of all charges against her. She was never charged with terrorism-related offenses.“Aafia Siddiqui Sentenced in Manhattan Federal Court to 86 Years for Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Crimes,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 23, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/September10/siddiquiaafiasentencingpr.pdf; “Aafia Siddiqui Found Guilty in Manhattan Federal Court,” U.S. Department of Justice, February 3, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/February10/siddiquiaafiaverdictpr.pdf; David Ingram, “Pakistani woman embraced by Islamic State seeks to drop U.S. legal appeal,” Reuters, September 18, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-courts-siddiqui-idUSKBN0HD0DR20140918. Thousands protested across Pakistan following her conviction.“Pakistanis protest Terror Mom verdict,” New York Post, February 4, 2010, http://nypost.com/2010/02/04/pakistanis-protest-terror-mom-verdict/. That September, Siddiqui was sentenced to 86 years in prison.“Aafia Siddiqui Sentenced in Manhattan Federal Court to 86 Years for Attempting to Murder U.S. Nationals in Afghanistan and Six Additional Crimes,” U.S. Department of Justice, September 23, 2010, https://www.justice.gov/archive/usao/nys/pressreleases/September10/siddiquiaafiasentencingpr.pdf.

Since her incarceration, Siddiqui has attained what media and analysts have called “superstar” status among terror groups, NGOs, and in her native Pakistan.Carol J. Williams, “Islamic State has offered to trade hostages for imprisoned ‘superstar,’” Los Angeles Times, September 19, 2004, http://www.latimes.com/world/middleeast/la-fg-islamic-state-siddiqui-20140919-story.html. In 2010, Pakistani public outcry led then-Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani and other Pakistani politicians to, unsuccessfully, lobby for Siddiqui’s release. Gilani described Siddiqui as a “daughter of the nation.”Salman Masood and Carlotta Gall, “U.S. Sees a Terror Threat; Pakistanis See a Heroine,” New York Times, March 5, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/06/world/asia/06pstan.html. The Pakistani government reportedly paid for Siddiqui’s legal fees.Benazir Shah, “The silence of Aafia Siddiqui,” Al Jazeera, July 16, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2015/07/silence-aafia-siddiqui-150714120601502.html. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan called for Siddiqui’s release in 2019.Holly McKay, “Pakistani PM opens door to prisoner swap with US to free 'hero' doctor who helped track bin Laden,” Fox News, July 23, 2019, https://www.foxnews.com/politics/pakistan-pm-prisoner-doctor-laden. Executed ISIS hostage Alan Henning worked for the British charity Aid4Syria, which has lobbied for Siddiqui’s release. The charity has also named projects after her, such as the “Afia Siddiqui Fire Brigade” and “Aafia Siddiqui Water Project.”Rukmini Callimachi and Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura, “ISIS releases video of execution of British aid worker,” New York Times, October 3, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/04/world/middleeast/islamic-state-releases-video-of-execution-of-alan-henning-british-aid-worker.html; Gordon Rayner, Bill Gardner, Tom Whitehead, and Ben Farmer, “Alan Henning charity campaigned for release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda’ Aafia Siddiqui,” Telegraph (London), September 16, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11099969/Alan-Henning-charity-campaigned-for-release-of-Lady-al-Qaeda-Aafia-Siddiqui.html.

Multiple extremist groups have offered to trade hostages for Siddiqui. In 2012, the Taliban offered to trade captured U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl.Shane Harris, “Lady al Qaeda: The World’s Most Wanted Woman,” Foreign Policy, August 26, 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/08/26/lady-al-qaeda-the-worlds-most-wanted-woman/. That year, al-Qaeda also offered to release hostages in exchange for Siddiqui and other U.S. prisoners.Raisa Bruner, “Warren Weinstein’s Wife Pleads for His Release,” ABC News, August 13, 2012, http://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/warren-weinsteins-wife-pleads-release/story?id=16994808. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) unsuccessfully sought to exchange hostages for Siddiqui and Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahma, a.k.a. the Blind Sheikh.“Yemen's al Qaeda leader says U.S. refused to trade ‘blind sheikh’ for hostage,” Reuters, March 6, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-tradecenter-rahman-aqap-idUSKBN16D2BA. In July 2014, ISIS demanded Siddiqui’s release in exchange for captured American aid worker Kayla Mueller, whose family wrote to then-U.S. President Barack Obama asking him to accept the exchange. Mueller died in early 2015.Shane Harris, “Kayla Mueller's Family Asked U.S. to Give ISIS ‘Lady al Qaeda,’” Daily Beast, February 11, 2015, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/02/11/muellers-hoped-kayla-might-be-traded-for-jailed-terrorist-siddiqui.html; Sam Levin, “Isis widow charged for her role in the death of hostage Kayla Mueller,” Guardian (London), February 8, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/08/isis-widow-charged-for-her-role-in-the-death-of-hostage-kayla-meuller. ISIS also offered to exchange American hostages James Foley and Steven Sotloff for Siddiqui.Gordon Rayner, Bill Gardner, Tom Whitehead, and Ben Farmer, “Alan Henning charity campaigned for release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda’ Aafia Siddiqui,” Telegraph (London), September 16, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11099969/Alan-Henning-charity-campaigned-for-release-of-Lady-al-Qaeda-Aafia-Siddiqui.html; Brian Ross, Rhonda Schwartz, and James Gordon Meek, “ISIS Demands $6.6M Ransom for 26-Year-Old American Woman,” ABC News, http://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/isis-demands-66m-ransom-26-year-american-woman/story?id=25127682. Siddiqui’s family has publicly called on ISIS to release hostages held as bargaining chips for Siddiqui.Dean Nelson and Raf Sanchez, “‘Free British hostages’ say family of Isil poster girl,” Telegraph (London), September 19, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iraq/11109612/Free-British-hostages-say-family-of-Isil-poster-girl.html.

Siddiqui twice sought to appeal her conviction. In 2012, she argued that her trial had been unfair because the judge had allowed her to decide whether she would take the stand. Siddiqui also argued that prosecutors had used improper evidence. An appeals court rejected her appeal that November.David Ingram, “Pakistani woman embraced by Islamic State seeks to drop U.S. legal appeal,” Reuters, September 18, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-courts-siddiqui-idUSKBN0HD0DR20140918. Siddiqui last filed for appeal in May 2014, arguing that she had not been allowed to change her Pakistan-funded legal team. But that July, she wrote to a federal judge requesting he drop her legal appeal.David Ingram, “Pakistani woman embraced by Islamic State seeks to drop U.S. legal appeal,” Reuters, September 18, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-courts-siddiqui-idUSKBN0HD0DR20140918. A federal judge accepted her request that October, ending Siddiqui’s right to further appeals.David Ingram, “Pakistani woman acclaimed by Islamists allowed to end U.S. appeal,” Reuters, October 9, 2014, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-courts-siddiqui-idUSKCN0HY2AF20141009.

In January 2021, Siddiqui began holding multiple meetings with her lawyer, Marwa Elbially of Elbially Law Office, PLLC. On July 30, 2021, another inmate allegedly smashed a coffee mug filled with a hot liquid in Siddiqui’s face in her cell. Elbially reported seeing multiple burns on Siddiqui’s face. Siddiqui was placed in administrative solitary confinement following the incident. That August, the advocacy group CAGE called for Siddiqui’s release.“Aafia Siddiqui calls for public support after enduring serious assault in Texas prison,” CAGE, August 19, 2021, https://www.cage.ngo/aafia-siddiqui-calls-for-public-support-after-enduring-serious-assault-in-texas-prison. Pakistan’s Representatives of Pakistan’s consul general in Houston, Texas, met with Siddiqui after the attack. Pakistan’s Foreign Office filed a complaint with U.S. authorities.Naveed Siddiqui, “Dr Aafia Siddiqui sustained ‘minor injuries’ in assault by fellow inmate in US prison: FO,” Dawn, August 21, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1641831.

Advocates continue to call for Siddiqui’s release. CAGE has issued multiple reports and videos calling for Siddiqui’s release.“Aafia Siddiqui calls for public support after enduring serious assault in Texas prison,” CAGE, August 19, 2021, https://www.cage.ngo/aafia-siddiqui-calls-for-public-support-after-enduring-serious-assault-in-texas-prison. A Facebook group calling for Siddiqui’s freedom has garnered more than 66,000 followers.Free Aafia Siddiqui Facebook group, accessed January 15, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/FreeAafiaSiddiquiNow. On October 20, 2021, members of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), the Islamic Leadership Council of New York, and approximately 20 other human-rights and religious groups protested outside the Pakistani consulate in New York City calling on the Pakistani government to seek Siddiqui’s repatriation. The organizers planned similar protests in Boston and Washington, D.C.“US protesters demand release and repatriation of Aafia Siddiqui,” Al Jazeera, October 21, 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/21/us-pakistan-protests-release-neuroscientist-aafia-siddiqui. Protests calling for Siddiqui’s freedom were also held in Pakistan that month.“Pakistan: Activists call for protest at National Press Club in Islamabad Oct. 7,” GardaWorld, October 6, 2021, https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts/531856/pakistan-activists-call-for-protest-at-national-press-club-in-islamabad-oct-7; Zia ur-Rehman and Michael Levenson, “Officials Investigating Synagogue Attacker’s Link to 2010 Terror Case,” New York Times, January 17, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/17/world/europe/texas-synagogue-hostages-aafia-siddiqui.html. In December 2021, CAIR’s Dallas-Fort Worth chapter organized a rally at the East Plano Islamic Center (EPIC) featuring speakers from both groups calling for Siddiqui’s release.“In Pursuit of Freedom for Dr. Aafia Siddiqui: EPIC & CAIR-TX,” CAIR-Texas Central-North, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.cairdfw.org/index.php/component/content/article/213-in-pursuit-of-freedom-for-dr-aafia-siddiqui-epic-cair-tx?catid=9&Itemid=101. In August 2021, CAIR’s chapter in Austin and Dallas-Fort Worth has also created a campaign to raise enough awareness and pressure to have Siddiqui freed.“About the Free Dr. Aafia Movement,” Free Dr. Aaafia Campaign, accessed January 28, 2022, http://www.freedraafia.org/index.php/about. On December 10, that chapter of CAIR organized a legal fund for Siddiqui, which raised $4,150 of a $60,000 goal by its end on January 12, 2022. The campaign called Siddiqui’s case “one of the greatest examples of injustice in U.S. history.”“Free Dr. Aafia Siddiqui Fund,” LaunchGood, accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.launchgood.com/campaign/free_dr_aafia_siddiqui_fund#!/.

In September 2021, radical Islamist preacher Anjem Choudary issued a call on his Telegram channel for Siddiqui’s freedom. He wrote, “The obligation upon us is to either free her physically or to ransom her or to exchange her.”Annabelle Timsit, Souad Mekhennet, and Terrence McCoy, “Who is Aafia Siddiqui? Texas synagogue hostage-taker allegedly sought release of ‘Lady al-Qaeda,’” Washington Post, January 16, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/01/16/aafia-siddiqui-texas-synagogue-hostages/. On January 15, 2022, 44-year-old British national Malik Faisal Akram entered the Congregation Beth Israel synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, during Saturday morning services, which were being livestreamed on the synagogue’s Facebook page. He took at least four hostages and began demanding Siddiqui’s release. An FBI SWAT team was called to the scene. Akram reportedly demanded to speak with Siddiqui.Jake Bleiberg, “Ranting man takes hostages at Texas synagogue,” Associated Press, January 15, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/religion-texas-fort-worth-70bf98670cb880156cf5e1f1e4e08dcd; Alaa Elassar, Michelle Watson, and Alanne Orjoux, “FBI identifies hostage-taker at Texas synagogue,” CNN, January 16, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/16/us/colleyville-texas-hostage-situation-sunday/index.html. In an unconfirmed report to ABC News during the hostage crisis, a U.S. official initially identified the hostage-taker as Siddiqui’s brother.Shelby Tauber and Daphne Psaledakis, “Police respond to "hostage situation" at Texas synagogue,” Reuters, January 15, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/police-colleyville-texas-involved-standoff-synagogue-media-2022-01-15/. Police were called to the synagogue by 11 a.m. The attacker reportedly claimed to have a bomb. Multiple people listening to the livestream of the synagogue’s service also reported hearing the attacker refer to Siddiqui as his sister, but a representative of CAIR told the Associated Press that Siddiqui’s brother, Mohammad Siddiqui, was not involved. One hostage was released just after 5 p.m. By 9:30 p.m., all hostages had been released and authorities declared Akram had been killed.Jake Bleiberg, Eric Tucker, and Michael Balsamo, “Hostages safe after standoff inside synagogue; captor dead,” Associated Press, January 15, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/religion-texas-fort-worth-70bf98670cb880156cf5e1f1e4e08dcd; Alaa Elassar, Michelle Watson, and Alanne Orjoux, “FBI identifies hostage-taker at Texas synagogue,” CNN, January 16, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/16/us/colleyville-texas-hostage-situation-sunday/index.html.

Investigators initially suspected Akram may have been motivated by a desire to have Siddiqui released. Siddiqui’s attorney, Elbially, denied Siddiqui had any involvement in the synagogue attack. Elbially said Siddiqui “does not want any violence perpetrated against any human being, especially in her name.”Andy Rose, “Aafia Siddiqui ‘has absolutely no involvement’ in synagogue hostage situation, her attorney says,” CNN, January 15, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/us/live-news/texas-synagogue-hostage-situation/h_bdb43b3cd460d8686fb0352d1a6f08e7. A law enforcement source told media Akram stated during the hostage crisis he knew would die and wanted Siddiqui brought to the synagogue so they could die together.Morgan Rousseau, “Aafia Siddiqui, the federal prisoner at the center of the Texas synagogue hostage situation, has Boston ties,” Boston.com, January 17, 2022, https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2022/01/17/texas-synagogue-aafia-siddiqui-boston-education/. Congregation Beth Israel is 24 miles from the Federal Medical Center, Carswell, in Fort Worth, where Siddiqui is incarcerated. The FBI continues to investigate the influence of Siddiqui’s case on Akram.Zia ur-Rehman and Michael Levenson, “Officials Investigating Synagogue Attacker’s Link to 2010 Terror Case,” New York Times, January 17, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/17/world/europe/texas-synagogue-hostages-aafia-siddiqui.html. Using the hashtags #FreeAafia and #IAmAafia, a January 19 Facebook post by CAIR Austin and Dallas-Fort Worth executive director Faizan Syed decried inaccurate news coverage of Siddiqui “made to paint a victim of the war on terror as a terrorist.”Faizan Syed Page, Facebook post, January 19, 2022, https://www.facebook.com/FaizanSyedPage/posts/448368146667807.

Siddiqui made news once again in May 2023, when a user on Rocket.Chat—a decentralized platform popular among ISIS media operatives—published a post claiming Siddiqui was granted a visitation by her sister after 20 years. The post provided an email address and a WhatsApp number for her supporters to send short letters to show that “she has not been forgotten.”“On ISIS Encrypted Server, User Calls On Supporters To Send Letters To Jailed Pakistani Neuroscientist Linked To Al-Qaeda Aafia Siddiqui; Claims Her Sister Will Visit Her Soon,” Middle East Media Research Institute, May 22, 2023, https://www.memri.org/jttm/isis-encrypted-server-user-calls-supporters-send-letters-jailed-pakistani-neuroscientist-linked. On May 31, Siddiqui and her sister were reunited at Carswell, the prison medical facility in Fort Worth, Texas, where they reportedly talked about what could be done to secure her release.“Aafia Siddiqui meets her sister after 20 years,” Dawn, June 1, 2023, https://www.dawn.com/news/1757163.

Cameron Shea is an alleged member of the Atomwaffen Division, a neo-Nazi group that grew out of a white supremacist forum called Iron March in 2016.“Atomwaffen Division (AWD),” Anti-Defamation League, https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/atomwaffen-division-awd. Shea was arrested in Seattle, Washington on February 26, 2020 on a conspiracy charge accusing him of sending threatening mail and cyberstalking. On April 7, 2021, Shea pleaded guilty federal conspiracy and hate crime charges and is still awaiting sentencing.“Leader of Neo-Nazi group ‘Atomwaffen’ pleads guilty to hate crime and conspiracy charges for threatening journalists and advocates,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 7, 2021, https://www.justice.gov/usao-wdwa/pr/leader-neo-nazi-group-atomwaffen-pleads-guilty-hate-crime-and-conspiracy-charges.

According to media reports, Shea was an alleged high-ranking recruiter for Atomwaffen Division’s chapter in Washington.Ali Winston, “Atomwaffen Division’s Washington State Cell Leader Stripped of Arsenal in U.S., Banned from Canada,” The Daily Beast, October 19, 2020, https://www.thedailybeast.com/kaleb-james-cole-atomwaffen-divisions-washington-state-leader-stripped-of-arsenal-in-us-banned-from-canada. Atomwaffen Division describes itself as a revolutionary socialist organization centered on political activism seeking to put an end to the “cultural and racial displacement of the white race.”“Atomwaffen Division (AWD),” Anti-Defamation League, https://www.adl.org/resources/backgrounders/atomwaffen-division-awd.

Shea and the leader of Atomwaffen Division’s Washington chapter, Kaleb Cole, were the primary organizers of an operation they dubbed Erste Saule. Translated to “first pillar” in German, Shea described the operation as a way to target “journalists houses and media buildings to send a clear message.”Mike Baker, Adam Goldman and Neil MacFarquhar, “White Supremacists Targeted Journalists and a Trump Official, F.B.I. Says,” New York Times, February 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/us/atomwaffen-division-arrests.html. Primarily seeking to target black or Jewish journalists, Shea and Cole sought to make their victims feel “terrorized.” The goal, Shea claimed, was to “erode the media/states air of legitimacy by showing people that they have names and addresses, and hopefully embolden others to act.”Mike Baker, Adam Goldman and Neil MacFarquhar, “White Supremacists Targeted Journalists and a Trump Official, F.B.I. Says,” New York Times, February 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/us/atomwaffen-division-arrests.html.