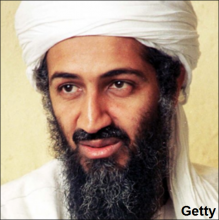

Executive Summary:

Osama bin Laden founded al-Qaeda during the latter stages of the Soviet-Afghan War with the goal of waging global jihad. Since its founding in 1988, al-Qaeda has played a role in innumerable terrorist attacks, and is most notoriously responsible for the multiple attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001. The 9/11 terror attacks—the deadliest ever on American soil—left nearly 3,000 people dead and provoked the United States to wage war against al-Qaeda in the group’s home bases in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other sanctuaries worldwide. Since then, the group has established five major regional affiliates pledging their official allegiance to al-Qaeda: in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, East Africa, Syria, and the Indian subcontinent.

In addition to directing and carrying out the 9/11 attacks, al-Qaeda is responsible for terrorist atrocities across the globe, including the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the 2002 Bali bombing, the 2003 Saudi Arabia bombings, the 2004 Madrid bombing, and the 2005 London bombing. Al-Qaeda is also responsible for several failed operations, including the 2009 Christmas Day plane bombing attempt, the 2010 Times Square bombing attempt, and the 2010 cargo plane bombing attempt. Today, al-Qaeda’s structure is increasingly decentralized, with affiliates acting semi-autonomously as extensions of al-Qaeda’s core mission. These affiliates carry out fatal terrorist attacks and hostage operations, and wage war under the al-Qaeda banner. Although al-Qaeda maintains affiliates worldwide, some of its affiliates have pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda’s former affiliate in Iraq and current competitor, ISIS. However, despite the dramatic rise of ISIS since 2013, the Pentagon, the National Counterterrorism Center, and the U.S. House Intelligence Committee have all forcefully stressed that al-Qaeda remains a critical terrorist threat. This assessment was borne out in January 2015, when al-Qaeda’s Yemeni affiliate, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), was credited with the deadly attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo that left 12 people dead. Despite important strategic and ideological differences, Zawahiri has indicated that future cooperation with ISIS is not out of the question, for the ultimate goal of destroying the United States or, in the event of ISIS’s own destruction, absorbing its fighters into a reinvigorated al-Qaeda. In April 2017, Iraqi Vice President Ayad Allawi confirmed that al-Qaeda was seeking an alliance with ISIS, as Iraqi forces closed in on Mosul, ISIS’s last key stronghold. Allawi claimed discussions were occurring between representatives of Baghdadi and Zawahiri.

With the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021 following the U.S. military withdrawal, U.S. military leaders remain concerned al-Qaeda will reestablish and grow its base in that country. The United States has warned the Taliban against allowing al-Qaeda to thrive in Afghanistan. U.S. assessments indicate al-Qaeda could rebuild its Afghanistan base within one to two years. Despite the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan, the U.S. military has declared its intentions to use airstrikes to restrict al-Qaeda in the country.

Doctrine:

Al-Qaeda is a jihadist network that seeks to establish a caliphate (global Muslim state) under sharia (Islamic law). In 1996, bin Laden issued a declaration of jihad against the United States and its allies, the contents of which continue to serve as the three cornerstones of al-Qaeda’s doctrine: to unite the world’s Muslim population under sharia; to liberate the “holy lands” from the “Zionist-Crusader” alliance, and to alleviate perceived economic and social injustices.

Ultimately, al-Qaeda believes that it is fighting a “defensive jihad” against the United States and its allies, defending Muslim lands from the “new crusade led by America against the Islamic nations…” In his 1996 declaration of jihad against the United States, Osama bin Laden justified the use of force by citing 13th century Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyyah: “To fight in defence of religion and Belief is a collective duty; there is no other duty after Belief than fighting the enemy who is corrupting the life and the religion. There [are] no preconditions for this duty and the enemy should be fought with [one’s] best abilities.”

Since then, the group has adapted its strategy in an effort to meet its evolving goals. In 2005, details of al-Qaeda’s 20-year strategy to implement its ideology emerged. Following a series of interviews and correspondence with senior al-Qaeda officials by Jordanian journalist Fouad Hussein, he described the “stages” leading to the ultimate objective of establishing a caliphate. According to Hussein, the first stage was the “awakening stage,” which ranged from the 9/11 attacks to the U.S. taking over Baghdad in 2003. This period was then to be followed by the “opening eyes” stage which was expected to last between 2003 and 2006. According to Hussein, this stage entailed enhanced al-Qaeda operations in the Middle East, centralizing power in Iraq, and establishing bases in other Arabic states. The third stage, “Arising and Standing Up,” was staged to last between 2007 and 2010 and was focused on goading Syria to conduct attacks on Israel and Turkey. The following three years, 2010 to 2013, would involve the overthrow of Arabic monarchies and cyber-attacks on the United States economy. The declaration of the caliphate would come between 2013 and 2016.

However, al-Qaeda’s planned declaration of a caliphate was usurped by ISIS. In September 2015, on the eve of the 14th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri denounced ISIS for its so-called unilateral and premature imposition of a caliphate without coordination with other jihadist groups through sharia courts, which he calls the “prophetic method.” In particular, Zawahiri expressed his dismay that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had anointed himself the fourth caliph “without consulting the Muslims.” Zawahiri also strongly criticized infighting among jihadist groups, especially the killing of other Muslims because, according to Zawahiri, it distracted from the overriding goal of destroying the United States.

Since then, and despite the local-oriented activities of al-Qaeda’s regional affiliates, Zawahiri maintained that the group’s primary target is the United States and “its ally Israel, and secondly its local allies that rule our countries.” Despite al-Qaeda’s criticism of ISIS, Zawahiri did not rule out the possibility of cooperating with ISIS, or absorbing its fighters if ISIS is eventually defeated. In April 2017, the Iraqi vice president confirmed that an al-Qaeda-ISIS merger was a possibility as the government had seen reports of high-level talks between the two groups. Despite the collapse of ISIS’s caliphate in 2019, al-Qaeda and ISIS continued to cooperate in West Africa’s Sahel region, raising concerns of future coordination between the groups.

Organizational Structure:

Al-Qaeda’s central command, which included former leader Ayman al-Zawahiri and his top aides, has traditionally been headquartered in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Al-Qaeda has long pledged allegiance to the Afghan-based Taliban, which provided sanctuary to al-Qaeda after the United States turned its military focus on the group following the 9/11 attacks. In June 2016, Zawahiri reaffirmed al-Qaeda’s allegiance by publicly endorsing the Taliban’s new leader, Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada.

Since the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent U.S.-led campaign against the organization’s base of operations, al-Qaeda spawned affiliate groups that have spread throughout North Africa and the Sahel, East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and most recently, South Asia. Despite the affiliates’ dispersal over such a vast area, the commander of each branch has pledged allegiance to—and takes operational directions from—al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Since the May 2011 death of Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda’s affiliates have taken on more central roles as al-Qaeda’s core has become more decentralized. Zawahiri brokered mergers with a number of Islamist groups including al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (previously the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat or GSPC) and al-Shabaab.

In North Africa and the Sahel, al-Qaeda is represented by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its breakaway factions. In East Africa, the group is represented by Somali-based al-Shabaab. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which many security analysts believe poses the greatest security threat to Western targets, operates primarily in Yemen. Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) is the most recent regional al-Qaeda affiliate to be established, operating chiefly in India, Bangladesh, as well as in the traditional al-Qaeda “home” countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. For years, al-Qaeda sustained a formal affiliate in Syria, al-Nusra Front (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham). In July 2016, the groups announced that they had split, a move some analysts dismissed as artificial. Al-Nusra subsequently dissolved and was subsumed into a new, larger Syrian Islamist group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (“Assembly for the Liberation of the Levant” or HTS). While al-Nusra Front continues to operate under the HTS name, the group has since reverted back to its core of about 10,000 fighters, most of them belonging to al-Nusra Front.

Recent developments suggest that al-Qaeda’s primacy of command is not exclusive to the group’s geographical base in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In August 2013, Zawahiri appointed Nasir al-Wuhayshi, former head of AQAP, as deputy leader of al-Qaeda’s global organization. After Wuhayshi died in a U.S. airstrike in June 2015, Zawahiri appointed deputy leader Abu Khayr al-Masri, who was also killed in a U.S. airstrike. Zawahiri reportedly groomed Osama bin Laden’s son Hamza bin Laden for a senior leadership role prior to Hamza bin Laden’s death in 2019.

The 2011 death of bin Laden compounded with the deaths or arrests of other al-Qaeda leaders have degraded the group’s communications, financial support, and facilitation of terror attacks, according to the U.S. State Department. Nevertheless, al-Qaeda’s core remains a source of inspiration for its affiliate groups, according to the State Department.

On November 13, 2020, there were reports that Zawahiri may be dead or at least “completely off the grid.” The claim came from Hassan Hassan, the director of the U.S.-based Center for Global Policy (CGP), who has closely monitored the militant group’s activities over the years. According to Hassan—who corroborated the claim with sources close to al-Qaeda—Zawahiri had been seriously ill and had possibly died in mid-October due to natural causes. According to Arab News on November 20, security sources in Pakistan and Afghanistan as well as an al-Qaeda translator with close ties to the group, claimed Zawahiri died in Ghazni, Afghanistan, from “asthma because he had no formal treatment.” The exact date of Zawahiri’s death was not released, but a Pakistani anti-terror security officer claimed Zawahiri died sometime in November 2020. Saif al-Adel, one of Zawahiri’s chief deputies, was widely reported to be next in line to succeed Zawahiri as the leader of al-Qaeda.

In late February 2021, some British media began reporting that Adel is soon to be or may have already been named the leader of al-Qaeda. According to retired British Army officer Colonel Richard Kemp, Adel is highly respected among both al-Qaeda and ISIS. As such, some analysts expected Adel to begin recruiting from current ISIS fighters. Analysts told the Mirror Adel is a more effective leader than Zawahiri and could make al-Qaeda as dangerous as it was in 2001.

On March 12, 2021, al-Qaeda released a new video featuring Zawahiri’s voice addressing the plight of Rohingya Muslims in China. However, Zawahiri was not the main speaker, nor did he physically appear in the video, leading observers to question whether the video had used pieces of a previously recorded speech by Zawahiri. Al-Qaeda released another video on September 11, 2021, in which Zawahiri praised the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan as well as a January 2021 attack targeting Russian troops in Syria. Given that Zawahiri did not mention the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan in August, the video could have been recorded months earlier, fueling doubt over whether he was still alive. Almost a year later on July 31, 2022, Zawahiri was killed in a CIA drone strike in Kabul. The strike targeted a house reportedly belonging to a top aide to senior Taliban leader Sirajuddin Haqqani. Zawahiri had allegedly been staying in the house. The strike was the first U.S. drone strike in Afghanistan since the U.S. withdrew its forces in late August 2021. In late December 2022, al-Qaeda released an undated video narrated by Zawahiri. Nonetheless, al-Qaeda had still not announced a new leader as of early 2023. On February 13, 2023, the U.N. Security Council released a report stating that the predominant view held among member states is that Adel is the “de facto leader of Al-Qaida.” His leadership was not officially announced as the statement would also acknowledge that former leader Zawahiri was in Afghanistan upon the time of his death, a fact that would contradict the Afghan Taliban’s claims of not harboring known terrorists. On February 15, the U.S. Department of State reiterated that Adel is Zawahiri’s successor, and that he is currently based in Iran.

Financing:

In its early stages, al-Qaeda’s primary bankroller was its founder Osama bin Laden. Since then, al-Qaeda has come to rely on donations and extorted funds for financing. The CIA estimates that al-Qaeda maintained a $30 million annual budget prior to the 9/11 attacks, and that donations primarily made up this budget. A 2002 report by the Council on Foreign Relations identified a network of “charities, nongovernmental organizations, mosques, websites, intermediaries, facilitators, and banks and other financial institutions” that were serving to finance the terrorist organization.

Today, al-Qaeda receives funding from a wide range of sources, including private donors, Islamic charities and foundations, state sponsors, and from activities linked to drug trafficking, bank robbery, and hostage-taking. Nonetheless, wide-ranging sanctions by the United States, United Nations, Financial Action Task Force, and other international financial organizations have slowed the flow of money to the terror group. By 2009, al-Qaeda was reportedly suffering from negative cash flow and was forced to seek out new revenue streams as al-Qaeda recruits complained of being charged for weapons and other supplies. In October 2009, David S. Cohen, then-assistant Treasury secretary for terrorist financing, said that al-Qaeda was in its “weakest financial condition in several years.”

After bin Laden’s death in 2011, analysts questioned whether al-Qaeda could survive financially or if it had depended too much on bin Laden’s celebrity. But al-Qaeda had laid the groundwork for a new fundraising strategy based on drug trafficking and kidnappings to bolster its finances. A year before, a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration official had pointed to an “unholy alliance” between al-Qaeda and Colombian guerillas in the cocaine smuggling trade.

U.S. forces searching bin Laden’s Pakistani compound in May 2011 discovered a trove of financial records. Analysts believe that al-Qaeda’s structure of international affiliates necessitated a paper trail in order for the group’s leadership to maintain control of its affiliates’ finances. Receipts found in an al-Qaeda hideout in Mali in 2013 revealed al-Qaeda’s corporate-like financial structure. The group meticulously kept receipts and invoices for major and minor expenses, from propaganda trips to fresh produce and tea. According to William McCants, a former adviser to the State Department’s Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, “They have so few ways to keep control of their operatives, to rein them in and make them do what they are supposed to do. They have to run it like a business.”

Islamic Charities

Al-Qaeda has misused charities to enhance its cash flow. In 2004, for example, the U.S. government sanctioned the Sudan-based Islamic Relief Agency (ISRA) for funneling roughly $5 million to Maktab al-Khidamat, bin Laden’s al-Qaeda predecessor. ISRA is present in 40 countries around the world. According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, ISRA began collaborating with Maktab al-Khidamat in 1997. An ISRA leader was allegedly involved in planning to relocate bin Laden in the late 1990s. According to a December 2020 U.S. Senate investigation, the Obama administration in 2014 approved a $200,000 grant to the non-profit humanitarian agency World Vision United States, which was collaborating with ISRA at the time. World Vision ended its funding of ISRA after later learning of its designation.

Private Donors

During the 1990s, bin Laden built a network of private donors to al-Qaeda using contacts he established during the Soviet-Afghan war. Bin Laden’s early donors to al-Qaeda in the 1990s relied “on ties to wealthy Saudi individuals that he had established during the Afghan war in the 1980s,” according to the U.S. 9/11 Commission. In 2002, U.S. forces in Bosnia seized a cache of al-Qaeda documents that revealed a global network of private donors. Among the documents was a 1988 memorandum that identified a group of 20 Saudi financial donors, referred to as “the Golden Chain,” which included members of bin Laden’s family, as well as prominent wealthy Saudis such as Saleh Kamel and Khalid bin Mahfouz, and the Al-Rajhi family.

High-profile private donors to al-Qaeda also include: ‘Abd al-Rahman bin ‘Umayr al-Nu’aymi; ‘Abd al-Wahhab Muhammad ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Humayqani; Enaam Arnaout; Muhammad Yaqub Mirza; Shafi Sultan Mohammed al-Ajmi; Hajjaj Fahd Hajjaj Muhammad Shabib al-Ajmi; and Abd al-Rahman Khalaf Ubayad Juday al-Anizi.

By 2009, donations to al-Qaeda had reportedly slowed to a near halt. On June 3, 2009, bin Laden issued an appeal for “charity and support” for al-Qaeda’s affiliates in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In an audio message a week later, al-Qaeda’s Afghanistan leader, Mustafa Abu al-Yazid, said that the group lacked food, weapons, and other supplies. That August, then-deputy al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri entreated Pakistani Muslims in particular to “back the jihad and mujahideen with your persons, wealth.”

In October 2015, a U.S. airstrike killed Sanafi al-Nasr, a former senior al-Qaeda financial leader who had revived the group financially. Nasr had set up a fundraising network based in Iran, from where he transferred donations from around the Persian Gulf to al-Qaeda’s leadership in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Today, according to the U.S. State Department, al-Qaeda funding continues to come primarily from donations and the diversion of funds from Islamic charities.

Recruitment:

Al-Qaeda has focused its recruiting on the Middle East, where al-Qaeda’s holy war garners adherents from a wide variety of backgrounds. As of July 2023, there are an estimated 30 to 60 members from al-Qaeda’s leadership residing in Afghanistan, and an additional 400 al-Qaeda fighters located in the Taliban-ruled country.

Potential recruits are often identified due to the character of their faith. Recruiters patrol certain mosques known for extremist interpretations of Islamic texts and seek out the most curious or fervent believers. Recruits are quickly immersed in doctrines of martyrdom and jihad and instructed in the religious duty to establish the caliphate.

Local insurgent groups in the Middle East and North Africa have found that the al-Qaeda label itself helps to attract new members on the basis of al-Qaeda’s global revolutionary agenda. As counterterrorism scholar Daniel Byman notes, “Groups like al-Shabab often have an inchoate ideology; al Qaeda offers them a coherent—and, to a certain audience, appealing—alternative.”

In Europe, al-Qaeda has sought recruits from those marginalized by society. They have actively, if informally, recruited members from Europe’s prison system. In 2006, Steve Gough of the U.K.’s Prison Officers Association said he did not think there were “al-Qaida-controlled wings” yet in British prisons. Nonetheless, Gough noted that al-Qaeda was already recruiting prisoners who shared their cells or were held in cells nearby. In France, two of the alleged January 2015 Paris attackers, Amedy Coulibaly and Cherif Kouachi, met al-Qaeda’s “premiere European recruiter,” Djamel Beghal, in prison.

In recent years, both al-Qaeda and ISIS have reportedly focused their international recruitment efforts on young adults. Psychologists call this group “in-betweeners,” referring to young adults who have not solidified their identities. One example is Ahmad Khan Rahami, the 28-year-old naturalized Afghan-American who allegedly planted bombs in New York City and New Jersey in September 2016. Police discovered that Rahimi had praised bin Laden and deceased AQAP cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in his journal. Rahimi spent several weeks in Afghanistan and Pakistan in 2011, and his father believed he had radicalized on the trip.

In Pakistan, al-Qaeda entices recruits through a plethora of benefits. Documents recovered from bin Laden’s Pakistani compound in May 2011 revealed that married al-Qaeda fighters received seven days of vacation for every three weeks worked, while bachelors received five days of vacation per month. Married fighters received a monthly salary of $108, or more if they had more than one wife.

Al-Qaeda's online recruitment has grown increasingly sophisticated. Its broad goal has been twofold: to increase the charm of an austere existence rooted in religion and then to shame those who abstain from this duty. These dual messages are conveyed online in many ways. Jihadist-inspired rap music, video games, and comics have successfully cast holy war positively and pulled new recruits into the organization.

Training:

Al-Qaeda relies on multiple methods to train its fighters, ranging from physical training camps to propaganda. In May 2012, AQAP’s English-language magazine, Inspire, published instructions on how to carry out domestic terror attacks, focusing on arson. Also that month, al-Qaeda released a training manual for Western recruits, authored by American AQAP member Samir Khan. The manual included information to help Western recruits acclimate to life with al-Qaeda in the Middle East, though it also encouraged recruits to instead carry out terror attacks in their home countries. According to the manual, one of the “pillars of modern day jihad” is secrecy.

From the Lackawanna Six to Charlie Hebdo

Sahim Alwan was one of the “Lackawanna Six” from Buffalo, New York, who were convicted of supporting al-Qaeda after attending a terror training camp in Afghanistan in the spring of 2001. More than 10 years later, Saïd Kouachi, one of the perpetrators of the Charlie Hebdo killings, confirmed that he spent “a few months” training in small-arms combat, marksmanship, and other skills on display in videos of the military-style attack. Thus, despite the increase in lone-wolf incidents since 9/11, traditional terrorist operations, including recruitment and training at foreign camps, remain a threat to Western security today.

Training Camps

Al-Qaeda training camps are located in numerous countries around the globe. While allied with the Taliban, al-Qaeda established several training camps in Afghanistan, including the sprawling Tarnak Farms, where Osama bin Laden allegedly plotted 9/11. Most Afghan camps were destroyed during the U.S. invasion and occupation of the country after 9/11. Unfortunately, as Joshua E. Keating of Newsweek noted in January 2015, “Where once there were few sanctuaries for jihadists [i.e., primarily in Afghanistan], now there are many—in Syria and Iraq, Pakistan and Yemen, Nigeria and Somalia.” Today’s jihadist training camps are created by a dispersed membership of not only al-Qaeda core but also offshoots like AQAP and AQIM.

In Africa, AQIM ran a training camp for eight months in Timbuktu, Mali before France conducted an airstrike that destroyed the unassuming building. A cook and cleaner at the facility recalled, “[The building was] ringed by a perimeter fence topped with barbed wire” and “became the hub for AQIM's new recruits. They [the recruits] ate, slept and trained in the old Gendarmerie, turning some of its rooms into dormitories.”

Al-Qaeda also relies on proxy training facilities from like-minded terrorist outfits like Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LET) in Pakistan. The latter group allegedly plotted the 2008 Mumbai attacks. Keating notes that:

The camps these groups run are often small, just one or two buildings, and temporary — such groups stay on the move to avoid detection by satellite or intelligence agents. These groups are believed to be increasingly sharing resources when it comes to training. According to some estimates, there are about 40 militant training camps around Pakistan.

Nonetheless, in late 2015, U.S. and Afghan forces discovered a large training camp in Qandahar Province, suggesting that al-Qaeda has “expanded its presence in Afghanistan.”

Indoctrination

In addition to physical training, indoctrination through study, videos, prayer, and a generally regimented lifestyle is meant to reinforce the singular message of jihad that al-Qaeda wishes to inspire in its trainees. Alwan noted that at the camp he attended, there was a billboard displaying a Quranic message that said, “Prepare for them what you can of strength so they may cast fear in the enemies of God.”

An al-Qaeda manual found in May 2000 further illustrates the degree of indoctrination that jihadists face in camp. The 180-page “handwritten terror instruction book” is dubbed the “Manchester Manual” because British anti-terror police found it in a raid on the apartment of al-Qaeda commander Abu Anas al-Liby in Manchester, England. Liby was wanted for plotting the 1998 U.S. embassy attacks in Kenya and Tanzania. The manual provides significant insight on the type of training al-Qaeda soldiers receive beyond physical training. Specifically, according to the U.S. Joint Task Force Guantanamo, “The Manchester Manual is literally an overarching basic guide that simply covers just about everything. It covers how to conduct general combat operations, how to escape and evade capture and how to behave in captivity. There is even a chapter on how to poison yourself using your own feces.”

Much of the information in the manual was corroborated by Guantanamo Bay detainees regarding al-Qaeda operative training. For example, Omar Sheik [a kidnapper of Daniel Pearl] told his interrogators that he was trained in… the art of disguise... secret rendezvous techniques; hidden writing techniques; [and] cryptology and codes... Moreover, Khalid Sheik Muhammad—the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks—admitted that he assisted the hijackers in preparing to live a Western lifestyle by instructing them how to order food at restaurants and wear Western clothes, amongst other things. Furthermore, an al-Qaeda training manual entitled, “Declaration of Jihad Against the Country’s Tyrants (Military Series), written primarily with the stated purpose of helping operatives avoid detection when infiltrating an enemy area, teaches lessons in forging documents and counterfeiting currency, living a cover, cell compartmentalization, and meeting and communicating clandestinely…

Today, there are numerous ideological offshoots that either continue to support or have deviated from al-Qaeda in the Middle East and other regions. As mentioned above, al-Qaeda itself continues some training camps but also increasingly outsources to allied groups in countries such as Pakistan. The need for such camps to remain under the radar will only grow as more countries band together to fight ISIS (which has more than 40 camps in Iraq and Syria alone) and other violent extremist groups like al-Nusra Front and Boko Haram.