Foreign Fighters

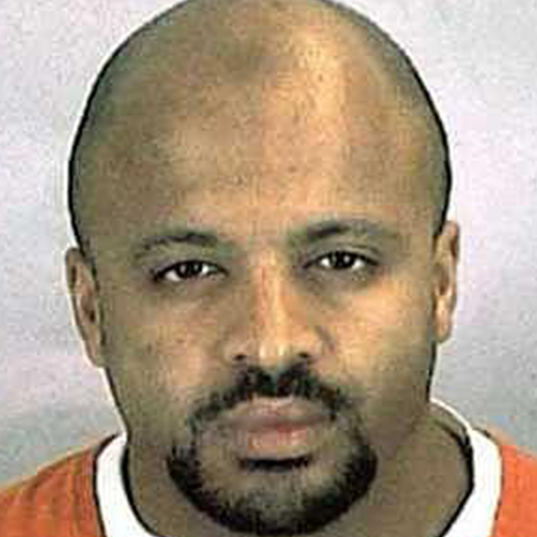

Zacarias Moussaoui is a convicted member of al-Qaeda and the alleged, would-be 20th hijacker in the 9/11 terror plot. Moussaoui was arrested on August 16, 2001, almost a month before the attacks on September 11, 2001. He was tried and convicted of conspiracy charges and was sentenced to life in prison in 2006.“Moussaoui formally sentenced, still defiant,” NBC News, May 4, 2006, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/12615601/ns/us_news-security/t/moussaoui-formally-sentenced-still-defiant/#.WUFcCGgrJEY. Moussaoui is currently imprisoned in a maximum-security prison in Colorado.Jerry Markon and Timothy Dwyer, “Jurors Reject Death Penalty For Moussaoui,” Washington Post, May 4, 2006, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/05/03/AR2006050300324.html.

Moussaoui, of Moroccan descent, was born in France on May 30, 1968.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. Before 2001, he lived in the United Kingdom, having obtained a masters’ degree in international business from South Bank University in London in 1995.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui;

“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html. While in the United Kingdom, Moussaoui reportedly frequented mosques with suspected ties to al-Qaeda, such as one where U.N.-sanctioned terrorist Abu Hamza al-Masri served as a prayer leader.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui. During this time, Moussaoui also traveled to Afghanistan to attend an al-Qaeda training camp.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 275-6, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. According to his indictment, he was present at the Khalden camp in Afghanistan, an al-Qaeda-affiliated training facility, in April of 1998.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui.

According to the 9/11 Commission, 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) sent Moussaoui to Malaysia in the fall of 2000 to enroll in flight training there, but Moussaoui was unable to find a school that he liked and instead began working on other terrorist plots. KSM instructed him to return to Pakistan and to attend flight training in the United States instead. Moussaoui returned to London in October of 2000, and began sending inquiries to a flight school in the United States.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 225, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Moussaoui is suspected to have made a second trip to Afghanistan via Pakistan in late 2000. He departed England for Pakistan on December 9, 2000, returning on February 7, 2001.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui.

After returning from Pakistan in February 2001, Moussaoui traveled to the United States under the Visa Waiver Program, which allows citizens of select countries, including France, to enter the United States for up to 90 days without a visa.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. After arriving in the United States at Chicago, Moussaoui enrolled in a beginner flight course at the Airman Flight School in Norman, Oklahoma.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. He stopped attending his course in May 2001, but remained in the United States after his allotted 90-day legal stay.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. According to the 9/11 Commission, he was a very inexperienced pilot at this point, having undergone only about 50 hours of flight time and no solo flights. Nonetheless, he began making inquiries about flight materials and simulator training for Boeing 747s. On July 10, he made a deposit of $1,500 for a flight simulator training course at the Pan Am International Flight Academy in Eagan, Minnesota. Soon after, he received a schedule for training between August 13 and August 20.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 246-7, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The course was designed for experienced pilots who already had commercial licenses.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm.

Around this time, Moussaoui also purchased knives and made inquiries about GPS equipment. According to the 9/11 Commission, these were “activities that closely resembled those of the 9/11 hijackers during their final preparations for the attacks.”National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 247, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. In July 2001, KSM instructed 9/11 facilitator Ramzi bin al-Shibh to wire $15,000 to Moussaoui in the United States. Bin al-Shibh later reported that he did not know the reason for this instruction, but assumed that it was “within the framework” of the 9/11 operation. The 9/11 Commission suspects that KSM may have considered Moussaoui a potential substitute for hijacker-pilot Ziad Jarrah, as there were concerns that Jarrah might drop out of the operation.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 246, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Later, however, KSM claimed that he never actually considered letting Moussaoui participate in the 9/11 attacks, and instead intended for him to participate in a future “second wave” of attacks.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 247, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Bin al-Shibh later claimed that KSM did not approve of Moussaoui, only intending to use him as a last resort, but that Moussaoui had been selected for the 9/11 operation by Osama bin Laden himself.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 247, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html.

On August 10, 2001, Moussaoui drove from Oklahoma to Minnesota. Three days later, he paid $6,800 in cash to Pan Am for his flight simulator training. His conduct––including the cash payment and lack of experience––raised suspicious. While the typical student in Pan Am training held a commercial pilot license, was employed by an airline, and had several thousand flight hours, Moussaoui claimed that he had no intention of becoming a commercial pilot and instead said that he wanted to learn to “take off and land” planes because it was an “ego boosting thing.” Furthermore, he specifically asked to fly a simulated flight from London’s Heathrow Airport to New York’s JFK airport.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 247, 273, 540, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. His instructor became suspicious and reported him to the FBI’s Minneapolis Field Office on August 15.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. On August 16, Moussaoui was arrested by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) on immigration charges, as he had outstayed his legal stay under the Visa Waiver Program. A deportation order for Moussaoui was signed on August 17.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 247, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

During an investigation, the FBI quickly realized that Moussaoui held fundamentalist beliefs. He also behaved suspiciously in other ways, such as reacting strongly to questions about materials in his laptop and about his membership in a group.“A Review of the FBI’s Handling of Intelligence Information Related to the September 1 Attacks: Chapter Four: The FBI’s Investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui,” Office of the Inspector General, November 2004, https://oig.justice.gov/special/s0606/chapter4.htm. According to the 9/11 Commission, he became “agitated” when he was questioned regarding his religious beliefs, and when asked about his travels to Pakistan. He said he planned to receive martial arts training and purchase a GPS, and could not provide an explanation for the $32,000 in his bank account. After the investigation, a FBI agent concluded that Moussaoui was “an Islamist extremist preparing for some future act in furtherance of radical fundamentalist goals,” and even concluded that he might be planning to hijack a plane.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 273-4, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

At the time of his arrest, Moussaoui possessed two knives, flight manuals and software programs for a Boeing 747, fighting gloves and shin guards, and a computer disk regarding the use of aerial pesticides.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui. Nonetheless, FBI headquarters in Washington deemed there to be insufficient probable cause to obtain a criminal warrant to search Moussaoui’s laptop, so Minneapolis agents sought to prove that Moussaoui was acting as an agent of a foreign power, contacting authorities in France and Britain throughout August and early September. At one point, a CIA message to the British government even described Moussaoui as a possible “suicide hijacker.” French authorities were able to reveal a connection between Moussaoui and a rebel leader in Chechnya, but this was still not enough to obtain a warrant.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 274, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

After 9/11, authorities moved Moussaoui to New York and held him as a material witness.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. On September 13, British authorities received information that Moussaoui had attended an al-Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 275-6, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Additionally, after the attacks, authorities found that he possessed bin al-Shibh’s contact information and discovered that he had received funds from bin al-Shibh.Sarah Downey, “Who Is Zacarias Moussaoui?” NBC News, December 14, 2001, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/3067363/t/who-zacarias-moussaoui/#.WUFWZWgrJEZ. The 9/11 Commission believes that the 9/11 plot could have been uncovered had authorities investigated further and discovered Moussaoui’s communications with bin al-Shibh before the attacks.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 276, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The Commission concluded, “FBI headquarters [did] not recognize the significance of the information regarding Moussaoui’s training and beliefs and thus [did] not take adequate action…to determining what Moussaoui might be planning.”National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 356, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

On December 11, 2001, Moussaoui was indicted by a federal judge on six conspiracy accounts.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. The charges, as listed on the indictment published by the U.S. Department of Justice, included conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism transcending national boundaries, conspiracy to commit aircraft piracy, conspiracy to destroy aircraft, conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction, conspiracy to murder United States employees, and conspiracy to destroy property.“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui. On December 13, Moussaoui was denied bail and moved to Alexandria, Virginia, to await trial.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. Nonetheless, in the following years, Moussaoui’s trial would face various delays and complications.

Moussaoui asked to represent himself in his trial. He was granted the right to do so in June of 2002 following a court-ordered mental evaluation.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. That same year, Judge Leonie Brinkema entered multiple pleas of “not guilty” on Moussaoui’s behalf, due to his lack of cooperation and her belief that he did not properly understand the law and the case against him.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788;

“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html. The prosecutors in the case sought the the death penalty for Moussaoui.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788.

According to NPR, Moussaoui was prone to “intemperate rants” and other unprofessional conduct throughout his trial.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. In November of 2003, Brinkema would remove Moussaoui’s right to represent himself in court, citing his unprofessional and inflammatory behavior.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. He was removed from the courtroom in February 2006 due to a disruptive outburst in which he declared, “I am al Qaeda. I am a sworn enemy.”“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html.

In May 2003, Moussaoui claimed that he had not been preparing for the 9/11 attacks, but for a different al-Qaeda operation. In June 2004, the 9/11 Commission concluded that Moussaoui’s precise role in the 9/11 attacks was “unclear.”“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html. On April 22, 2005, Moussaoui pled guilty to all six charges against him.“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html. On March 27, 2006, in a blow to his defense, Moussaoui testified that he had been training to crash a plane into the White House in a fifth attack on 9/11 with accomplices that included so-called “shoe bomber” Richard Reid. He also testified that he lied to authorities after his arrest so that the 9/11 attacks would proceed as planned. On April 3, jurors determined that Moussaoui was responsible for at least one death in the 9/11 attacks, and was therefore eligible for the death penalty.“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788.

On April 17, Michael First, a widely respected psychiatrist, testified that Moussaoui was schizophrenic and suffered from delusions and disorganized thinking. First testified that Moussaoui had a frequent delusion of President George Bush freeing him from prison as part of a prisoner exchange with al-Qaeda.Phil Hirschkorn, “Defense experts call Moussaoui schizophrenic,” CNN, April 19, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/LAW/04/19/moussaoui.trial/index.html;

“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788. A clinical psychologist named also Xaiver Amador testified that Moussaoui’s delusions were what had led him to claim his involvement in the 9/11 attacks. Amador suggested that Moussaoui’s alleged schizophrenia may have also been the reason that he had experienced so much difficulty in his flight training.Phil Hirschkorn, “Defense experts call Moussaoui schizophrenic,” CNN, April 19, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/LAW/04/19/moussaoui.trial/index.html.

On May 3, the jury rejected the death penalty for Moussaoui in favor of a life sentence in prison without parole. The jury rejected the defense’s argument that he suffered from mental illness. Additionally, the jury rejected a second argument that the death penalty would effectively allow him to die as he desired––as a martyr. However, the jury still preferred a life sentence in prison over the death penalty, due to doubts that Moussaoui actually played a significant role in the 9/11 attacks despite his own claims that he did.“Moussaoui formally sentenced, still defiant,” NBC News, May 4, 2006, http://www.nbcnews.com/id/12615601/ns/us_news-security/t/moussaoui-formally-sentenced-still-defiant/#.WUFcCGgrJEY. Testimony given in April 2006 by Mohammed al-Kahtani, an al-Qaeda member captured in December 2001, suggested that Kahtani had been the intended 20th hijacker in the 9/11 attacks rather than Moussaoui.Phil Hirschkorn, “Defense experts call Moussaoui schizophrenic,” CNN, April 19, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/LAW/04/19/moussaoui.trial/index.html. Furthermore, an al-Qaeda audiotape was released in 2006 in which bin Laden stated that he “never assigned brother Zacarias” to be part of the 9/11 attacks.Kristina Sgueglia and Deborah Feyerick, “9/11 terrorist Zacarias Moussaoui claims Saudi involvement,” CNN, November 18, 2014, http://www.cnn.com/2014/11/17/world/zacarias-moussaoui-saudi-arabia/index.html?iref=allsearch. On May 13, Moussaoui was transferred to the highest security prison in the United States, a maximum-security facility in Florence, Colorado.Phil Hirschkorn, “Defense experts call Moussaoui schizophrenic,” CNN, April 19, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/LAW/04/19/moussaoui.trial/index.html;

“Timeline: The Case Against Zacarias Moussaoui,” NPR, May 3, 2006, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5243788.

In February 2008, Moussaoui’s lawyers requested a federal appeals court to revoke Moussaoui’s guilty plea on the grounds that some of his U.S. constitutional rights had been violated during the trial. However, this appeal was rejected in January 2010, and the 4th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals reaffirmed Moussaoui’s guilt and life sentence.“Zacarias Moussaoui Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated June 12, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/03/us/zacarias-moussaoui-fast-facts/index.html.

While in prison, Moussaoui wrote multiple letters to courts claiming that he had inside knowledge about al-Qaeda, asking to testify in terrorism-related lawsuits, and making various other demands.Curt Anderson, “’20th hijacker’ Zacarias Moussaoui seeks transfer to Guantanamo,” Miami Herald, December 10, 2014, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article4409077.html. Moussaoui wrote two handwritten letters that were filed in federal court in November 2014. In these letters, he claimed that while taking flying lessons in Oklahoma, Saudi royalty gave him money to fund the 9/11 plot. He also claimed that he had been privy to a Saudi plot to shoot down Air Force One in order to assassinate former U.S. president Bill Clinton and his wife, Hillary Clinton, on a visit to the United Kingdom.Kristina Sgueglia and Deborah Feyerick, “9/11 terrorist Zacarias Moussaoui claims Saudi involvement,” CNN, November 18, 2014, http://www.cnn.com/2014/11/17/world/zacarias-moussaoui-saudi-arabia/index.html. In December 2014, he wrote two letters to a federal judge in south Florida requesting a transfer to the Guantanamo Bay military prison in Cuba on the grounds that he was being harassed by other inmates, including Ramzi Yousef, mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, at his maximum-security prison in Colorado. He signed the letters as the “so-called 20th hijacker” and “Slave to Allah.”Curt Anderson, “’20th hijacker’ Zacarias Moussaoui seeks transfer to Guantanamo,” Miami Herald, December 10, 2014, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article4409077.html.

In 2015, Moussaoui wrote letters to Army Colonel James L. Pohl, the judge in the 9/11 war crimes trial of five Guantanamo Bay inmates charged in relation to the attacks.“About the 9/11 war crimes trial,” Miami Herald, May 15, 2017, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article1928877.html;

Carol Rosenberg, “’20th hijacker’ wants to testify at Guantanamo’s 9/11 trial,” Miami Herald, March 23, 2017, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article140400503.html. Moussaoui reportedly offered to give testimony about “the real 9/11 mastermind” in this letter, naming members of the Saudi royalty as key conspirators and donors.Carol Rosenberg, “’20th hijacker’ wants to testify at Guantanamo’s 9/11 trial,” Miami Herald, March 23, 2017, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article140400503.html;

“About the 9/11 war crimes trial,” Miami Herald, May 15, 2017, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article1928877.html. In response, the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia distributed a press release claiming that there was no factual basis for Moussaoui’s claims. The release stated that the 9/11 Commission cleared Saudi Arabia of any wrongdoing and that Moussaoui was a “deranged criminal.”“Saudi Embassy Dismisses Moussaoui’s Allegations,” Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia, February 3, 2015, https://www.saudiembassy.net/saudi-embassy-dismisses-moussaouis-allegations.

In January 2017, Moussaoui again wrote Pohl, stating that he would be willing to testify in the 9/11 trial, even if it meant that he would be incriminated with the death penalty. Edward MacMahon, a former defense attorney for Moussaoui, has speculated that Moussaoui wrote letters and asked to testify not out of any true desire to help but rather because “he would like to be in the spotlight and is bored in solitary.”Carol Rosenberg, “’20th hijacker’ wants to testify at Guantanamo’s 9/11 trial,” Miami Herald, March 23, 2017, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo/article140400503.html.

In April 2020, Moussaoui filed a handwritten motion in Alexandria, Virginia federal court in which he renounced terrorism and al-Qaeda. The motion denounced “Osama bin Laden as a useful idiot of the CIA/Saudi [Arabia],” and “proclaim[ed] unequivocally” Moussaoui’s “opposition to any terrorist action, attack, propaganda against the US.” He further stated that he wanted to “warn young Muslims against the deception and manipulation of these fake jihadis.” Moussaoui’s alleged condemnation of jihadism was part of a petition seeking to ease his prison conditions. The judge denied his request and said that any further grievance over his prison conditions should be filed in Colorado, where he is serving his sentence.Associated Press, “Only man convicted over 9/11 says he is renouncing terrorism and Bin Laden,” Guardian, May 20, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/20/zacarias-moussaoui-september-11-al-qaida-bin-laden.

- Shaqil“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui.

- Abu Khalid al Sahrawi“Indictment of Zacarias Moussaoui,” U.S. Department of Justice, December 11, 2001, https://www.justice.gov/archives/ag/indictment-zacarias-moussaoui.

International terrorist: Convicted member of al-Qaeda and the alleged would-be 20th hijacker in the 9/11 terror plot. Serving a life sentence in a maximum-security prison in Colorado.

Allegedly attended London’s Brixton mosque in the 1990s while Faisal served as imam, though Faisal claims Moussaoui joined the mosque after he had left.

Gregory Hubbard is an American citizen who was arrested on July 21, 2016, along with Dayne Atani Christian and Darren Arness Jackson, for conspiring and attempting to provide material support to ISIS. Hubbard expressed praise and support for ISIS and ISIS-related acts of terrorism, and also made arrangements to travel to Syria with a confidential FBI source in order to join ISIS and engage in acts of terrorism. He was arrested at Miami International Airport before his intended departure.“Two Florida Men Plead Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIL,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 4, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/two-florida-men-plead-guilty-conspiring-provide-material-support-isil;

“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

Hubbard was born in Albany, Georgia.John Pacenti, “ISIS in Florida: Former FBI agent on why arrests didn’t come sooner,” Palm Beach Post, July 24, 2017, http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/crime--law/isis-florida-former-fbi-agent-why-arrests-didn-come-sooner/Pezdh6eBg1C3B1zVDMKVuI/. He entered the U.S. Marine Corps at age 19, working in aviation supply, but later made his living as an artist and sculptor.Mimi Pirrault, “ISIS in Florida: 2007 Post profile of artist Gregory Hubbard,” Palm Beach Post, July 23, 2016, http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/crime--law/isis-florida-2007-post-profile-artist-gregory-hubbard/PyoJHEAZtb9tLmY2M2eqhM/;

Paula McMahon, “Guilty pleas expected for two Palm Beach County men arrested in terror sting,” Sun Sentinel, March 14, 2017, http://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/palm-beach/fl-reg-palm-beach-terror-sting-update-20170314-story.html. Hubbard reportedly became depressed and homeless after falling victim to fraud, although court records reveal that he sought treatment for his mental health issues.Skyler Swisher, “Three Palm Beach County men plead not guilty in alleged conspiracy to help terrorists,” Sun Sentinel, July 27, 2016, http://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/palm-beach/fl-palm-isil-arraignment-20160727-story.html;

Paula McMahon, “Guilty pleas expected for two Palm Beach County men arrested in terror sting,” Sun Sentinel, March 14, 2017, http://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/palm-beach/fl-reg-palm-beach-terror-sting-update-20170314-story.html.

At some point in 2015, Hubbard was contacted by a confidential FBI informant pretending to be an ISIS follower.Paula McMahon, “Second man pleads guilty in Palm Beach terrorism sting,” Sun Sentinel, April 4, 2017, http://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/palm-beach/fl-pn-terrorism-sting-plea-palm-beach-20170403-story.html;

“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 5, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Hubbard––also known as “Jibreel”––introduced the FBI informant to Christian on August 15, 2015, and to Jackson on May 11, 2016.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 4-5, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. The FBI informant would record more than 200 hours of conversation among Christian, Jackson, and Hubbard over the course of the subsequent year.Jane Musgrave, “Second PBC man pleads guilty in plot to help ISIS,” Palm Beach Post, April 4, 2017, http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/crime--law/second-pbc-man-pleads-guilty-plot-help-isis/8o3UPtnn7sX8YgYv0trNCP/. The men reportedly used code words to communicate, including the phrase “soccer team” in reference to ISIS, and “playing soccer” in reference to violent activity.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 5, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

Hubbard was known to engage with and propagate extremist propaganda on multiple occasions, including ISIS videos and lectures by the American al-Qaeda cleric Anwar al-Awlaki. In April of 2015, Hubbard emailed the FBI informant a 100-page manual in e-book form published by ISIS for its supporters. Hubbard told the informant that he previously wrote two articles that he sent to ISIS for publication, and was currently working on a third.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 6, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. He sent the manual to the informant again on November 2, also mentioning some ISIS-related videos that he had watched.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 7, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. In June 2016, Hubbard discussed violent ISIS videos with Christian and the FBI source, expressing “favorable views” of at least one of the videos, according to the criminal complaint filed against him.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 13, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On other occasions that same month, Hubbard played an Awlaki lecture on his phone for the FBI informant and sent a group text message containing a link to an Awlaki video that encouraged violent jihad.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 15, 18, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

Hubbard also explicitly expressed support and praise for ISIS and ISIS-related acts of terrorism, as detailed by the criminal complaint filed against him. On one occasion, he stated that there were only two types of people, those with ISIS and those against ISIS, and deemed ISIS to be “exciting.”“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 6, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. He also stated that “jihad is the skin of Islam” and that the only way to deal with one’s enemy was to “cut off his head.”“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 7, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Hubbard publicly praised the December 2, 2015 mass shooting in San Bernardino and claimed that the attack and other instances of violent jihad were justified by the U.S.-led airstrikes in Syria.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 7-8, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. He also praised the 2009 mass shooting in Fort Hood, Texas, stating that the shooter did the right thing.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 8, 10, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On another occasion, Hubbard told Christian that if he left town, would leave behind ammunition for one of Christian’s “own mission[s],” according to the criminal complaint filed against him.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 17, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Hubbard stated that he “wanted to bring America to its knees” and hoped that ISIS would attack the Pentagon or the White House.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 10, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. In July 2016, Hubbard praised both the terrorist attack in Nice, France, and the shooting of police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the day after each respective attack occurred.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 19, 20, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

Hubbard intended to travel to Syria to join ISIS and wage violent jihad there, making definite arrangements for his travel. He applied for a renewed passport in August of 2015 and received it on December 9.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 6, 8, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Upon receiving it, Hubbard became “excited” and stated that it was time to travel to Syria, according to the criminal complaint filed against him.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 8, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On March 3, 2016, Hubbard indicated to the FBI informant that he wanted to leave soon, and discussed logistics concerning flights, storage of personal belongings, and finances.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 11-12, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Later that month, he stated that he intended to depart that summer and not return to the United States.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 12, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On May 17, Hubbard solicited the FBI informant’s opinion on travel routes to Syria.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 12, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. Later that month, in preparation for his departure, Hubbard packed his personal belongings into a rental moving truck and transported them to a storage unit in Albany, Georgia.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 13, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On June 7, Hubbard booked an airline ticket from Miami, Florida, to Berlin, Germany, and researched train travel from Berlin to Istanbul, Turkey, where he intended to travel before crossing the border to Syria. He also sold his van a few days later.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 15, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On June 20, Hubbard and the FBI source booked a hotel reservation for Berlin, as Hubbard wanted it to appear that they were legitimate tourists.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 17, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On July 18, Hubbard discussed finances for the trip with the FBI informant, declaring that he would bring $6,000. On this date, Hubbard also gave the FBI informant several boxes of his artwork to store at the informant’s place of residence, stating that he did not plan to return from Syria.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 20-21, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

Also in preparation for his travel to Syria, Hubbard attended target practice at local shooting ranges with Jackson, Christian, and the FBI source between May and July of 2016.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. At one practice, Hubbard remarked that he felt persecuted because he was Muslim and assumed that the others at the shooting range were training to kill Muslims.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 5-6, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf. On another instance, he brought his own weapons to the practice and provided his companions with instructions on the handling of firearms.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 15-16, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf.

On July 21, 2016, Jackson drove Hubbard and the FBI agent in his car from West Palm Beach to Miami International Airport, so that they could depart on a flight bound for Berlin, Germany, from where they planned to travel to Syria to join ISIS. Hubbard was arrested at the airport after he and the FBI informant obtained their boarding passes and cleared the TSA checkpoint.“United States of America v. Gregory Hubbard, Dayne Antani Christian, and Darren Arness Jackson,” George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, July 22, 2016, 21, https://cchs.gwu.edu/sites/cchs.gwu.edu/files/downloads/Hubbard%20Complaint.pdf;

“Two Florida Men Plead Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIL,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 4, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/two-florida-men-plead-guilty-conspiring-provide-material-support-isil.

On July 26, 2016, Hubbard was indicted with charges of conspiring and attempting to provide personnel to ISIS, a designated foreign terrorist organization, as he expressed support for ISIS and made an attempt to travel to Syria to join ISIS himself.“Two Florida Men Plead Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIL,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 4, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/two-florida-men-plead-guilty-conspiring-provide-material-support-isil. Although Christian and Jackson pled guilty to their charges of material support, Hubbard continued to fight his allegations.Paula McMahon, “Second man pleads guilty in Palm Beach terrorism sting,” Sun Sentinel, April 4, 2017, http://www.sun-sentinel.com/local/palm-beach/fl-pn-terrorism-sting-plea-palm-beach-20170403-story.html;

“Two Florida Men Plead Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIL,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 4, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/two-florida-men-plead-guilty-conspiring-provide-material-support-isil.

On February 8, 2018, Hubbard pleaded guilty to conspiring to provide material support to ISIS.Jennifer Tinter, “West Palm Beach Man Pleads Guilty to Conspiring with ISIS,” WPTV Channel 5, February 9, 2018, https://www.wptv.com/news/region-c-palm-beach-county/west-palm-beach/west-palm-beach-man-pleads-guilty-to-conspiring-with-isis; David J. Neal, “He Wanted to Join Islamic State. He Got as Far as Airport Security,” Miami Herald, February 13, 2018, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/state/florida/article199701919.html. On May 16, 2018, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison, followed by a lifetime of post-release supervision. His codefendants were sentenced on the same day: Christian was sentenced to eight years in prison, while Jackson was sentenced to four years in prison.“Three Florida Men Sentenced for Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIS,” U.S. Department of Justice – Office of Public Affairs, May 16, 2018, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-florida-men-sentenced-conspiring-provide-material-support-isis; Chuck Weber, “Men Sentenced in 'Homegrown' Terrorism Case,” CBS 12 News, May 16, 2018, https://cbs12.com/news/local/men-sentenced-in-homegrown-terrorism-case.

Hubbard is currently incarcerated at Schuylkill Federal Correction Institution in Pennsylvania, with a scheduled release date of November 21, 2026.“GREGORY HUBBARD,” Find an Inmate – Federal Bureau of Prisons, accessed April 7, 2021, https://www.bop.gov/inmateloc/.

- Jibreel“Two Florida Men Plead Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to ISIL,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 4, 2017, https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdfl/pr/two-florida-men-plead-guilty-conspiring-provide-material-support-isil./li>

Arrested on July 21, 2016 at the Miami International Airport before his intended departure to Syria. Charged with conspiring to provide material support to ISIS.

Discussed an ISIS video of a beheading with Dayne Atani Christian that he said that he also showed to an FBI undercover operative, as well as a video that depicted ISIS members crushing an individual’s skull with a large rock. Also received and forwarded a text message containing an audio recording of a speech released by former ISIS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani that advocated for attacks on civilians in the West. Played a lecture by the now-deceased AQAP recruiter Anwar al-Awlaki on his cell phone in the presence of an FBI undercover operative, and sent a group text message containing a link to an Awlaki lecture video encouraging violent jihad.

Hani Hanjour was the hijacker-pilot of American Airlines Flight 77, flown into the Pentagon as the third of the four 9/11 plane hijackings.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 10; 239, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Hanjour underwent pilot training in the United States in the 1990s, as the only pilot trained prior to being selected for the 9/11 plot.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 225-6, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. According to findings from the 9/11 Commission, Hanjour was specifically assigned to attack the Pentagon because he was the operation’s most experienced pilot.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 530, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

The 9/11 Commission Report summarizes Hanjour’s upbringing and some details regarding his path to radicalization. Hanjour reportedly traveled from his hometown of Ta’if, Saudi Arabia, to Afghanistan in the 1980s to participate in jihad against the Soviets, but ended up working in a relief agency because the war had already ended when he arrived. Hanjour, a “rigorously observant Muslim,” according to the Commission, first came to the United States in 1991 to take English as a Second Language classes at the University of Arizona. He returned again to the United States in 1996 to attend flight school, enrolling at schools in Florida, Arizona, and California, but did not progress far in his training and soon returned to Saudi Arabia. In 1997, Hanjour again returned to Arizona to undertake flight training, obtaining his private pilot’s license and, in April 1999, his commercial pilot certificate from the Federal Aviation Administration. The 9/11 Commission notes the possible significance of Hanjour’s time in Arizona, mentioning that Hanjour was known to have associated with other extremist individuals there. According to the report, various al-Qaeda-affiliated individuals lived in Tucson or attended the University of Arizona in the 1980s and 1990s, and other known extremists enrolled in aviation training there.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 225-6, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

After leaving the United States in April 1999, Hanjour spent some time at home in Saudi Arabia. He applied to a flight school in Jeddah, but was rejected. At some point, he told his family he was leaving for the United Arab Emirates to work for an airline, but is believed to have traveled to Afghanistan during this time instead. Hanjour was known to be in Afghanistan by the spring of 2000, where spent time at al-Faruq, an al-Qaeda training camp near Kandahar. He was sent to meet 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) in Karachi after either Osama bin Laden or al-Qaeda military commander Mohammed Atef found out that he was a trained pilot.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 226, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. All of the hijackers, including Hanjour, volunteered for suicide missions.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 234, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

Hanjour returned to Saudi Arabia on June 20, 2000, where he obtained a U.S. student visa on September 25. He then traveled to the United Arab Emirates to meet with 9/11 facilitator Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, who provided Hanjour with funds. On December 8, he traveled to San Diego, California, where he met up with fellow 9/11 hijacker Nawaf al Hazmi.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 226, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The two traveled to Arizona, where they rented an apartment together.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 226, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” accessed July 7, 2017, 111, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. Hanjour enrolled in refresher training at his old flight school, Arizona Aviation, and also trained at the Pan Am Internation Flight Academy in Mesa, but according to the 9/11 report, he was repeatedly advised to discontinue when instructors found his work “well below standard.” Nonetheless, Hanjour continued and completed his training in March of 2001, at which point he drove east with Hazmi to await the arrival of the “muscle hijackers,” who would help al-Qaeda’s pilots take over the 9/11 planes. They arrived in Falls Church, Virginia, by April 4, 2001.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 226-7, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

While in Falls Church, Hanjour and Hazmi attended the Dar al Hijra mosque, where al-Qaeda propagandist Anwar al-Awlaki served as an imam. There, they met a Jordanian man named Eyad al Rababah who helped them rent an apartment in Alexandria, Virginia. Rababah also helped them search for an apartment in Paterson, New Jersey, without success. He offered to take them to Connecticut to look for a place to live there instead. The 9/11 Commission suspects that Awlaki may have instructed Rababah to assist Hanjour and Hazmi.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 229-30, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. When two other 9/11 muscle hijackers, Ahmed al Ghamdi and Majed Moqed, arrived in the United States in early May, they moved into Hanjour and Hazmi’s apartment in Alexandria.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 528, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. On May 8, 2oo1, the four hijackers traveled from Virginia to Fairfield, Connecticut, with Rababah, allegedly to look for a place to live. That evening, Rababah drove the four to Paterson, New Jersey, then back to Connecticut, after which point he claims to never have seen them again.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 230, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” accessed July 10, 2017, 132, 141, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/.

The four hijackers returned to New Jersey and began renting an apartment in Paterson on May 21, 2001.“9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 10, 2017, 144, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/. They were joined there by three other 9/11 hijackers, Salem al Hazmi, Abdul Aziz al Omari, and Khalid al Mihdhar, in the subsequent weeks.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 230, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. While living in New Jersey, Hanjour opened a mailbox and bank account,“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 166-7, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. activated a cell phone,“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 168, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. rented a car,“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 198, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. obtained identification cards,“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 201, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. and even frequented a gym.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 243, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” accessed July 10, 2017, 132, 141, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/. Hanjour also continued flight training through August of 2001.“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 222, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/. On May 29, he flew along the Hudson River with Air Fleet Training Systems based in Teterboro, New Jersey, but was denied his second request to fly the route because of what his instructor deemed his “poor piloting skills.”“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 10, 2017, 150, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/;

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 242, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Hanjour then trained at the Caldwell Flight Academy in Fairfield, New Jersey, where he took a practice flight that passed Washington, D.C. the The pilot hijackers also did reconnaissance flights in the early summer of 2001, traveling in first class to case their aircraft-types and determine the feasibility of bringing and using box cutters to hijack the plane.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 242, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. On August 13, Hanjour and Hazmi flew from Washington, D.C., to Las Vegas, on a Boeing 757, returning via Minneapolis the following day.“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 217, 220, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/;

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 248, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. On August 31, Hanjour purchased his ticket for American Airlines Flight 77, bound from Washington, D.C. to Los Angeles, at a travel agency in New Jersey.“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 217, 220, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Hani Hanjour and the four other hijackers of American Airlines Flight 77 checked in between 7:15 and 7:35 a.m. for the flight, scheduled to depart at 8:10 a.m., at Washington Dulles International Airport.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 2-3, 8, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Hanjour and two others were selected by a computerized prescreening system at the airport, but were ultimately able to clear the security checkpoint and board the plane without issue. Hanjour sat in seat 1B, in the first-class cabin.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 3-4, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. American Airlines Flight 77 departed from the ground at 8:20 a.m.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 8, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

The plane hijacking on American Airlines Flight 77 began sometime between 8:51 and 8:54 a.m.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 8, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. According to reports from passengers and flight attendants who made calls before the plane crashed, the hijackers used knives and possibly box cutters to carry out the hijacking, forcing the passengers to move to the back of the plane so that Hani Hanjour could enter the cockpit and take control of the aircraft. At some point, Hanjour made an announcement that the plane had been hijacked.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 8, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. At 8:54 a.m., the aircraft veered off course, turning back toward Washington D.C., and at 9:00 a.m., communications with the plane were lost. At 9:34 a.m., the aircraft made a 330-degree turn and began a 2,200-ft descent toward downtown Washington, D.C. Hanjour advanced the aircraft’s throttles to maximum power and began a high-speed dive toward the Pentagon.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 9, 334, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. At 9:37 a.m., American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon at approximately 530 miles per hour, instantly killing everyone on board and an unknown number of people in the building.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 10, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The 9/11 attacks—including attacks on the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and the thwarted attack headed for the White House or Capitol—left nearly 3,000 people dead in the single deadliest attack in U.S. history.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 7, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

- Ha HanjourUnited States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, “Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” accessed July 10, 2017, 21, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hami HanjoorUnited States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, “Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” accessed July 10, 2017, 12, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hami Saleh HanjoorUnited States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, “Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” accessed July 10, 2017, 25, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- [email protected]“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 166, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/.

- Hani Hanjoor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 7, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Hanjou“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 25, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Hanjour-Hanjour“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 4, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Hanjur“The Plot and the Plotters,” National Security Archive, June 1, 2003, 1, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/368989/2003-06-01-11-september-the-plot-and-the.pdf.

- Hani S H Hanjoor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 10, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani S H Hanjour“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 10, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani S. H. Hanjoor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 8, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani S. H. Hanjour“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 4, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani S. Hanjour“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 21, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Saleh“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 5, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Saleh Hanjoor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 15, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Salih Hasan HanjurNational Security Archive, “The Plot and the Plotters,” Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Report, June 1, 2003, 48, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/368989/2003-06-01-11-september-the-plot-and-the.pdf.

- Hani Saleh Hassan“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 26, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hani Saleh Hassan Hanjoor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 15, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- [email protected]“9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 166, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-02-of-02/.

- [email protected]“9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed July 7, 2017, 88, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/.

- Hanjor“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 4, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

- Hany Saleh“Hijacker True Name Usage Chart for 2001,” United States District Court Eastern District of Virginia, accessed July 10, 2017, 4, http://www.vaed.uscourts.gov/notablecases/moussaoui/exhibits/prosecution/OG00013.pdf.

Abdul Aziz al Omari was one of the so-called “muscle hijackers” of American Airlines Flight 11, flown into the World Trade Center’s north tower as the first of the four 9/11 plane hijackings.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 231; 437, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. As a muscle hijacker, Omari helped to storm the cockpit and keep passengers under controlNational Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 227, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. so that the hijacker-pilot, Mohamed Atta, could take control of the plane. The flight’s hijackers used pepper spray and the threat of a bomb to carry out the hijacking, during which they stabbed at least two unarmed flight attendants and one passenger.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 5, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

Abdul Aziz al Omari was from Saudi Arabia’s Asir Province, an impoverished region in the country’s southwest. According to the 9/11 Commission, Omari was an accomplished student, having graduated from high school with honors and having obtained a degree from the Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University. He was married and had a daughter, and served as an imam at his mosque.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 232, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 02 of 02,” accessed July 7, 2017, 2, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/. According to an FBI report, in the summer of 2000, he traveled to al Qassim, a region at the core of the ultra-conservative Wahhabi Islamic movement in Saudi Arabia where two other 9/11 hijackers may have been radicalized.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 233, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

National Security Archive, “The Plot and the Plotters,” Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Report, June 1, 2003, 35, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/368989/2003-06-01-11-september-the-plot-and-the.pdf. The 9/11 Commission reports that he was a student of a radical Saudi cleric, Sulayman al Alwan, whose mosque, which was located there, has been dubbed a “terrorist factory” by other clerics.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 233, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

The 9/11 Commission reports that most of the Saudi muscle hijackers began to break with their families in 1999 or 2000, and that some claimed that they intended to wage violent jihad against Russian forces in Chechnya.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 232-33, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Omari reportedly expressed a desire to travel to Chechnya,National Security Archive, “The Plot and the Plotters,” Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Report, June 1, 2003, 35, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/368989/2003-06-01-11-september-the-plot-and-the.pdf. but as he was not one of the hijackers found to actually have documentation suggesting that they traveled to Russia, it is likely that this was a pretext for his travels to Afghanistan, where he reportedly spent most of the fall of 2000.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 232-33, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

National Security Archive, “The Plot and the Plotters,” Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Report, June 1, 2003, 35, https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/368989/2003-06-01-11-september-the-plot-and-the.pdf. Many of the hijackers reportedly intended to travel to Russia but were instead diverted to Afghanistan, where they volunteered to be suicide attackers after hearing Osama bin Laden’s speeches.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 232-33, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. Omari reportedly met 9/11 architect Khalid Sheikh Mohammed when he was working in security at the airport in Kandahar, Afghanistan.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 233-34, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The hijackers underwent basic training in weaponry use at al-Faruq, an al-Qaeda training camp near Kandahar in Afghanistan. All of the hijackers volunteered for suicide missions.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 234, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.

After completing their basic training sometime in 2000, the muscle hijackers were instructed to return to their home countries and acquire new passports and U.S. visas before returning to Afghanistan.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 234-5, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. It is unclear if Omari followed this protocol, as records show that he received his passport in Jeddah on June 5, 2000––before his initial travel to Afghanistan––and a U.S. visa from Saudi Arabia the following year, on June 18, 2001––days before he would depart for the United States.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 525, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf;

Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” accessed July 7, 2017, 68, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/. The 9/11 Commission reports that Omari’s passport was recovered after September 11, 2001.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 525, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. According to his passport stamps, he traveled to Bahrain, Egypt, Malaysia, and the United Arab Emirates in 2000 and 2001.Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” accessed July 7, 2017, 72, 141, 148, 157, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/. However, there is reason to doubt that he actually traveled to all of these countries, as the 9/11 Commission reports that Suqami’s passport was found to have been doctored by al-Qaeda.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 525, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. The FBI also reports that Malaysian entry stamps, in particular, were used to “disguise travel to and from Afghanistan.”Federal Bureau of Investigation, “9/11 Chronology Part 01 of 02,” accessed July 7, 2017, 141, https://vault.fbi.gov/9-11%20Commission%20Report/9-11-chronology-part-01-of-02/.

According to the 9/11 Commission Report, the so-called “muscle hijackers” returned to Afghanistan for special training in late 2000 or early 2001, where they learned to conduct hijackings. Again, it is unclear if Omari actually departed Afghanistan after he received training there in the fall of 2000.National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 235-6, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf. All of the muscle hijackers were personally chosen by bin Laden during this time, after which they committed to carrying out a suicide operation and filmed a so-called “martyrdom video.”National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, Thomas H. Kean, and Lee Hamilton. 2004. The 9/11 Commission report: final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. (Washington, D.C.): 235, http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/911/report/911Report.pdf.