Antisemitism: A History

Late Eighteenth Century Through Early Twentieth Century: A Jewish Family Conspiracy, Jewish Emancipation, the Blood Libel Emerges in the Middle East, the Dreyfus Affair, and the Rise of Zionism

After centuries of imposing restrictions on Jews, European nations slowly began to grant Jews expanded rights in the late eighteenth century. This period is known as Jewish Emancipation, the roots of which began in France during its revolution and spread through Western Europe over the course of the next two centuries. But while the nineteenth century brought new freedoms for Europe’s Jews, it also birthed some of the most well-known anti-Jewish conspiracies. As Jews were granted citizenship, the questions of Jewish loyalty and nationality became more pronounced. Were Jews a religion or also a nation? And if they were a nation, would they be more loyal to the Jewish nation than to the nation-state in which they resided? The Jewish question dominated French political debates at both the beginning and at the end of the nineteenth century.

In 1789, at the beginning of the French Revolution, the National Assembly of France passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. In line with the spirit of the revolution, the document declared the equality of men and laid the foundation for French democracy by outlining citizens’ civil rights, including the derivation of sovereignty from the nation itself, rather than from a monarch. Of particular interest to French Jews was the tenth article: “No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.” “Declaration of the Rights of Man – 1789,” Avalon Project, Yale Law School, accessed September 19, 2019, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/rightsof.asp. In December 1789, French nobleman Stanislas Marie Adélaïde argued before the National Assembly that Article X should include Jews. He declared: “The Jews should be denied everything as a nation, but granted everything as individuals.” Eli Barnavi, “Jewish Emancipation in Western Europe,” My Jewish Learning, accessed September 19, 2019, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/jewish-emancipation-in-western-europe/. France’s Constituent Assembly passed the declaration in 1791. Eli Barnavi, “Jewish Emancipation in Western Europe,” My Jewish Learning, accessed September 19, 2019, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/jewish-emancipation-in-western-europe/.

Napoleon Bonaparte resisted calls to expel his Jewish population in favor of a strategy to try to change their behavior. Bonaparte came to believe that to “chase away the Jews” would be “a sign of weakness,” while “it would be a sign of strength to correct them.” William Nicholls, Christian AntiSemitism: A History of Hate (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1993), 302. In 1806, Bonaparte received a petition from the citizens of Alsace-Lorraine, who found themselves unable to pay their debts to Jewish money-lenders. The pleas swayed Bonaparte to action, and he implemented a strategy to “correct” the Jews rather than expel them. France’s National Assembly passed a one-year moratorium on debts to Jewish lenders. Bonaparte convened a commission of well-to-do Jews and presented them with a series of questions regarding Jewish practice related to civil marriages, divorce, mixed marriages, usury, and whether French Jews would die to defend France—all with the intent of the commission endorsing the authority of the French state. In essence, Bonaparte was demanding loyalty—to France, French society, and French laws. Jews had long been accused of loyalty to the larger Jewish community over the states in which they lived, and Bonaparte sought to ensure Jewish loyalty to the state by offering Jews freedoms they had up to then been denied.

The commission agreed to abide by all of Bonaparte’s terms, but it lacked a central religious authority that would resonate with the French Jewish community. William Nicholls, Christian AntiSemitism: A History of Hate (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1993), 301-305. To gain this authority, Bonaparte convened a Sanhedrin, an assembly of notable French rabbis based on the assembly of learned rabbis in biblical Israel, which would debate and rule on questions of law. Bonaparte wished for the Sanhedrin to incorporate his demands into Jewish law in order for the Jews of France to view themselves as French citizens first and foremost. The French Sanhedrin met in 1807 and largely agreed to Bonaparte’s demands. The exception was the issue of mixed marriages, on which the Sanhedrin compromised and said that while Jewish law would not officially sanction them, it would recognize mixed marriages performed in civil ceremonies. William Nicholls, Christian AntiSemitism: A History of Hate (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1993), 301-305. As a result of this bargain with Bonaparte, France’s Jews became integrated French citizens in return for ceding some religious authority to the state. However, Bonaparte would later retract his promises and institute new limitations on Jewish life.

Bonaparte’s exile to Elba in 1814 and defeat at Waterloo the following year resulted in the reimposition of restrictions on Jews. In 1814, the Congress of Vienna convened to discuss a new German Federation comprised of 36 Germanic states. The Congress also took up the issue of the Jewish Emancipation that was taking hold in Europe and how Jews would fare in the new German Federation. Several of the Germanic states had begun to grant their Jewish citizens expanded rights. The final wording of the constitution provided for Jews to retain these rights granted “by” several of the federated states, but the word “by” was purposefully inserted in place of the word “in” to make the scope of where these rights were valid more ambiguous. William Nicholls, Christian AntiSemitism: A History of Hate (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1993), 305-307.

Prussia began to sell limited residential rights to Jews in the late seventeenth century—in exchange for large sums of money. Jews came to Berlin in 1669 when King Frederick I of Prussia allowed them to seek refugee after expulsion from Vienna. These refugees, however, were allowed to settle in Berlin only if they paid the requisite amount—2,000 thaler per person, or approximately $90,000 in today’s dollars. In 1710, the son of Frederick I, King Frederick William, allowed Jews in Berlin to remove the yellow patches from their clothing in exchange for a large sum of money. Frederick II went further and encouraged Jews to develop industry in Berlin. According to historian Phyllis Goldstein, Jews created 37 of the 46 new businesses in Prussia during Frederick II’s rule. Goldstein explained in her book A Convenient Hatred: The History of Antisemitism that Jews who could afford to buy these privileges or had a privileged relationship with the king became known as the “court Jews.” Rights were also granted to the wives and children of court Jews, but those rights were revoked in the case of death of the court Jew. Phyllis Goldstein, A Convenient Hatred: The History of AntiSemitism (Brookline: Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, 2012), 162-163. Frederick II himself died in 1786. Matthew Smith Anderson, “Frederick II,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, last updated August 13, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frederick-II-king-of-Prussia. Prussia finally granted citizenship to its Jews in 1812.Phyllis Goldstein, A Convenient Hatred: The History of AntiSemitism (Brookline: Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, 2012), 165.

Across Europe, Jews began to gain access to professions from which they had previously been blocked. Centuries of Jewish exclusion from other occupations and the prominence of Jews in a field frowned upon by Christian theology fueled the beliefs that Jews were unscrupulous and gave rise to stereotypes of Jewish greed, shrewdness, and financial acumen. Brigitte Sion, “Conspiracy Theories and the Jews,” My Jewish Learning, accessed September 19, 2019, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/conspiracy-theories-the-jews/. Historian Howard M. Sachar estimated that in the eighteenth century, “perhaps as many as three-fourths of the Jews in Central and Western Europe were limited to the precarious occupations of retail peddling, hawking, and ‘street banking,’ that is, moneylending.” Howard M. Sachar, “‘A History of the Jews in the Modern World,’” New York Times, September 4, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/04/books/chapters/a-history-of-the-jews-in-the-modern-world.html.

With the onset of the Emancipation, Jewish financiers also found new, wealthier, and politically prominent clients available to them, which resulted in the emergence of wealthy Jewish families such as the Rothschilds.

In the mid- to late-eighteenth century, Mayer Amschel Rothschild began to build a family business that would create one of Europe’s wealthiest dynasties and would also launch an enduring conspiracy theory of Jewish money and power. Born in the Frankfurt Judengasse, Rothschild built an empire trading in rare coins and currencies that eventually included providing financial services to Crown Prince Wilhelm of Hesse and the British Empire. By Rothschild’s death in September 1812, the business had expanded in Frankfurt and in England. His four sons had also joined the business, renamed M.A. Rothschild und Söhne. “Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812),” The Rothschild Archive, accessed October 2, 2019, https://family.rothschildarchive.org/people/21-mayer-amschel-rothschild-1744-1812. Today, the company owns properties in eight countries. “Rothschild Family Estates by Country,” The Rothschild Archive, accessed October 2, 2019, https://family.rothschildarchive.org/estates.

The Rothschild family’s great wealth and Mayer Rothschild’s royal and government business connections spawned conspiracy theories that the powerful family exercised control over world events and financial systems. Michael S. Rosenwald, “The Rothschilds, a pamphlet by ‘Satan’ and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories tied to a battle 200 years ago,” Washington Post, April 20, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/03/19/the-rothschilds-a-pamphlet-by-satan-and-conspiracy-theories-tied-to-a-battle-200-years-ago/. Those conspiracy theories, which still exist today, can be traced back to the nineteenth century. In 1846, a political pamphlet signed by “Satan” explained that Nathan Rothschild, one of Mayer’s sons, had been present at the 1815 Battle of Waterloo and witnessed Napoleon’s defeat. According to the pamphlet, Rothschild then rode furiously to the coast and, encouraged by Satan, paid a local fisherman for his boat because Rothschild’s ships were trapped by a storm over the English Channel. Rothschild returned to England before news of Waterloo spread there and made a fortune in the stock market exploiting his foreknowledge. Brian Cathcart, “The Rothschild Libel: Why has it taken 200 years for an anti-Semitic slur that emerged from the Battle of Waterloo to be dismissed?,” Independent (London), May 3, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-rothschild-libel-why-has-it-taken-200-years-for-an-anti-semitic-slur-that-emerged-from-the-10216101.html.

Versions of the pamphlet spread across Europe. It was later revealed that “Satan” was in fact left-wing conspiracy theorist and known antisemite Georges Dairnvaell. Rothschild had not been present at Waterloo, nor had he made any great fortune in the stock market at that time. Even the storm over the English Channel had been fabricated. Brian Cathcart, “The Rothschild Libel: Why has it taken 200 years for an anti-Semitic slur that emerged from the Battle of Waterloo to be dismissed?,” Independent (London), May 3, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/the-rothschild-libel-why-has-it-taken-200-years-for-an-anti-semitic-slur-that-emerged-from-the-10216101.html. Nonetheless, these facts failed to expunge the conspiracy theory from history. And today, the Rothschild dynasty is a favorite target of conspiracy theorists on both the far left and the far right, who claim everything from the Rothschilds controlling operations of the World Bank to the family’s responsibility for the onset of hurricanes.

As the Rothschild conspiracy theory began to spread throughout Europe, another ancient antisemitic canard was taking hold in the Middle East: the blood libel, the accusation that Jews used the blood of gentiles for ritual purposes.

The Ottoman Empire had largely ignored blood libel accusations against Jews, which became increasingly common in the first half of the nineteenth century. Phyllis Goldstein, A Convenient Hatred: The History of AntiSemitism (Brookline: Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, 2012), 188. However, two cases of the blood libel emerged in the Ottoman Empire in February 1840, one on the island of Rhodes and the other in Syria. In Rhodes, a Greek Orthodox boy disappeared that month and the Greek community blamed the Jews for his disappearance. The Ottoman governor of Rhodes publicly sided against the Jewish community. An investigation in July 1840 cleared the Jewish community of responsibility, but only after months of protests and outreach by the Rhodes Jewish community to their compatriots in Constantinople and other European capitals. Yitzchak Kerem, “The 1840 Blood Libel in Rhodes,” Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies (1997): 137-46, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23535855.

At the same time, in Ottoman-ruled Syria, Jews and Christians lived under the dhimmi status under the rule of Muhammad Ali, the Ottoman governor of Egypt who had united the two countries. The population of 100,000 in Damascus at the time included about 5,000 Jews and 12,000 Christians. That February, Catholic monk and French citizen Father Thomas and his Greek servant, Ibrahim Amarah, disappeared, allegedly after the pair had set off for the city’s Jewish quarter. Suspicion immediately fell upon Syria’s Jews. Crowds in Damascus protested that the Jews were responsible, while news articles in Paris blamed the Jews for murdering Thomas and Amarah and using their blood in Passover rituals. The French consul in Syria seemingly embraced this narrative as well, further legitimizing the libel. “The Damascus Blood Libel (1840) as Told by Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass,” MEMRI, June 27, 2002, https://www.memri.org/reports/damascus-blood-libel-1840-told-syrian-defense-minister-mustafa-tlass;

Phyllis Goldstein, A Convenient Hatred: The History of AntiSemitism (Brookline: Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, 2012), 183-204.

Ottoman authorities arrested a Jewish barber named Solomon Halek and tortured him until he confessed to the murder. According to the confession, a rabbi and a group of Jews oversaw the monk’s murder and collected his blood to serve during Passover. Seven of the city’s wealthiest and most influential Jews were subsequently arrested as well and confessed under torture. “The Damascus Blood Libel (1840) as Told by Syrian Defense Minister Mustafa Tlass,” MEMRI, June 27, 2002, https://www.memri.org/reports/damascus-blood-libel-1840-told-syrian-defense-minister-mustafa-tlass;

Phyllis Goldstein, A Convenient Hatred: The History of AntiSemitism (Brookline: Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, 2012), 183-204.

While the blood libel was taking hold in the Middle East, Europe continued to struggle with the question of Jewish loyalty to the nation-state. Despite the French Sanhedrin’s acquiescence to Bonaparte’s demands, he continued to pass laws that separated and restricted Jews from French society. After Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo, many Jews throughout Europe saw their new rights and freedoms granted during Emancipation rescinded and they returned to the ghettos. William Nicholls, Christian AntiSemitism: A History of Hate (Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc., 1993), 304-305. Jews were once again separated and viewed as the societal Other across Europe. Questions about Jewish loyalty led to Jews being viewed as an enemy within the state subservient to the broader Jewish community. This line of thinking was most prominently on display in late nineteenth-century France during what came to be known as the Dreyfus Affair.

In December 1894, French authorities convicted Jewish army Captain Alfred Dreyfus of treason for passing secret documents to the Germans. Dreyfus was sentenced to life in prison and spent five years on Devil’s Island in French Guiana. In 1896, new evidence arose identifying Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy as the real perpetrator. Esterhazy was acquitted after a two-day trial and new charges were presented against Dreyfus based on forged documentation. On January 13, 1898, French novelist Émile Zola wrote an open letter entitled “J’accuse!” in the French newspaper L’Aurore naming those behind the conspiracy to frame Dreyfus. The accusation sparked riots across France and retaliation against Jews. Dreyfus returned to France in 1899 but was not acquitted until 1906. Piers Paul Read, “France is still fractured by the Dreyfus Affair,” Telegraph (London), January 28, 2012, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/9045659/France-is-still-fractured-by-the-Dreyfus-Affair.html.

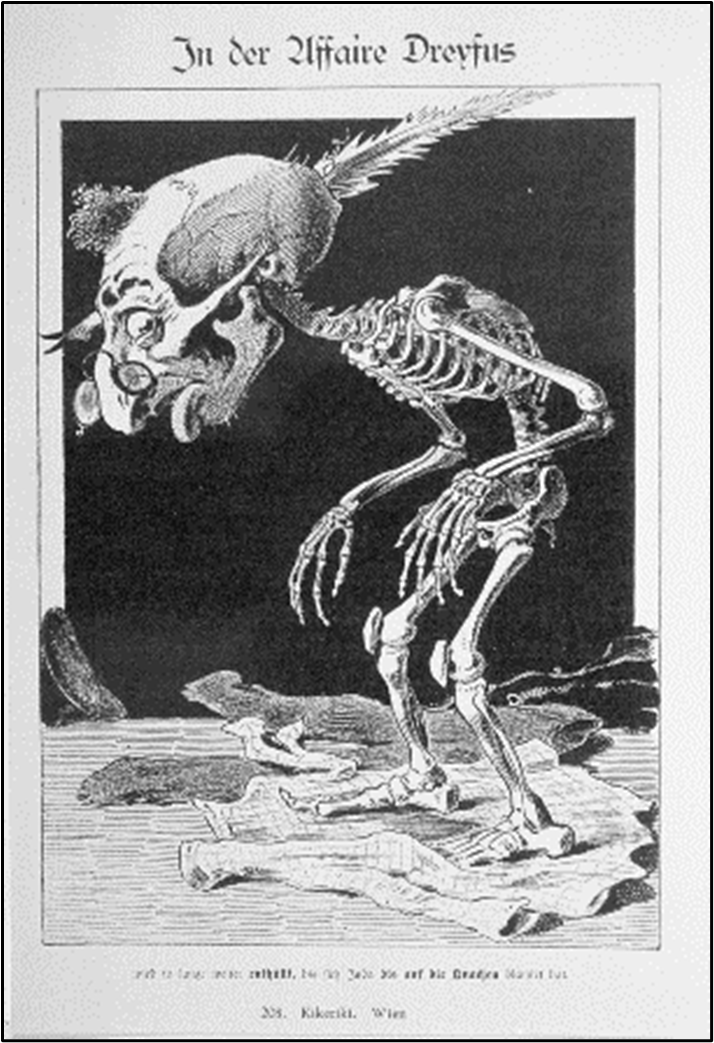

The Dreyfus Affair seemingly returned to the forefront Bonaparte’s worries about Jewish loyalty. The European public was quick to accept the notion that a Jewish soldier had committed treason and that his loyalty was to the larger Jewish community rather than the country he served. On April 23, 1899, as the Dreyfus Affair gripped France, the cover of Viennese magazine Kikeriki featured a hunched-over skeleton with a face full of stereotypical Jewish features. The caption read: “In the Dreyfus Affair, the more that is exposed, the more Judah is embarrassed.” U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum archive, accessed September 11, 2019, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1041718. The image played upon multiple stereotypes of dishonesty, disloyalty, and the hook-nosed Jew.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the Hungarian secular Jew Theodor Herzl was developing the concept of modern Zionism, the belief that Jews have a right to live as a free people in their historic homeland. Herzl witnessed the Dreyfus Affair firsthand as a journalist for a Viennese paper, which helped inform his beliefs that Jews could not receive justice in Europe. He wrote:

The Dreyfus case embodies more than a judicial error; it embodies the desire of the vast majority of the French to condemn a Jew, and to condemn all Jews in this one Jew. Death to the Jews! howled the mob, as the decorations were being ripped from the captain's coat.... Where? In France. In republican, modern, civilized France, a hundred years after the Declaration of the Rights of Man. The French people, or at any rate the greater part of the French people, does not want to extend the rights of man to Jews. The edict of the great Revolution had been revoked. Theodor Herzl, Der Judenstaat (New York: Dover Publications, 1988), 34.

Herzl proposed his solution in his 1896 book Der Judenstaat, “The Jewish State,” in which he called for the creation of a Jewish homeland, birthing the political Zionist movement that eventually led to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. Before reaching that milestone, however, the Jewish community of Europe would experience the most violent extended outbreak of state-institutionalized antisemitism in centuries, during the Holocaust in World War II.

The Jewish Emancipation came during a period when a new form of nationalism was spreading through Europe. As new countries emerged and sought to shape their national identities, the Jewish question—and specifically the question of Jewish loyalty—resurfaced. In late nineteenth century Germany, academics and other elites embraced their new unified German identity and rallied under the banner of the “völkisch (people’s) movement.” The roots of the völkisch movement can be traced back to the early nineteenth century, when a group of German students burned books at Wartburg Castle out of a belief that they were anti-German. After Germany’s 1871 unification, the philosophy coalesced and began to attract prominent philosophers and thinkers. By the 1890s, it had become a movement that increasingly spotlighted racial differences in the social order. Jews were no longer identified as a religious group but as a distinctive racial entity within Germany—an entity that was increasingly responsible for the country’s problems. Jefferson Chase, “AfD co-chair Petry wants to rehabilitate controversial term,” Deutsche Welle, September 11, 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/afd-co-chair-petry-wants-to-rehabilitate-controversial-term/a-19543222;

“AntiSemitism,” U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed November 28, 2018, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitism;

Guy Tourlamain, “Introduction” in “Völkisch” Writers and National Socialism: A Study of Right-Wing Political Culture in Germany, 1890-1960 (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2014), 1-22, 24-26, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2t4f2g.5. By the end of the nineteenth century, the movement was breeding a brand of racial antisemitism that would later dominate Germany under Nazism. It was during this time period that the term antisemitism itself first emerged. German writer Wilhelm Marr first used the term in an 1873 pamphlet entitled Der Sieg des Judentums uber das Germanentum (“The Victory of Judaism Over Germandom”). Eli Barnawi ed., A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People (New York: Shocken Books, 1994), 186.

A distinctive German antisemitism began to emerge, rooted in the fear of Jews gaining too much influence and power. The belief that Jews were orchestrating the Bolshevism emanating from Russia further ingrained fears of Jewish power. Eli Barnawi ed., A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People (New York: Schocken Books, 1994), 186. One 1898 French cartoon, entitled “Rothschild,” depicted a large-nosed Jew wearing a crown with an idol of a calf in the center while embracing a globe with his demon hands. “Antisemitic political cartoon entitled ‘Rothschild’ by the French caricaturist, C. Leandre, 1898,” U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed October 4, 2019, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1041697. An 1897 cartoon in the Viennese magazine Kikeriki depicted an exaggerated caricature of a Jewish merchant swindling an upstanding gentile citizen. Eli Barnawi ed., A Historical Atlas of the Jewish People (New York: Schocken Books, 1994), 186.

Jewish assimilation rates in Germany were actually increasing during this time. Some 12,000 Jews converted to Protestantism between 1889 and 1910, while others embraced the secularism of the world around them. Guy Tourlamain, “Introduction” in “Völkisch” Writers and National Socialism: A Study of Right-Wing Political Culture in Germany, 1890-1960 (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2014), 26, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2t4f2g.5. Writers who supported the völkisch movement, however, wrote that Jewishness was racial and no amount of assimilation could override inherent tendencies toward thievery, usury, and other negative traits that formed the basis of Jewish stereotype. The ideas of the völkisch movement became more widespread in the early twentieth century and Adolf Hitler drew inspiration from it as he began his political ascension in the 1920s. Jefferson Chase, “AfD co-chair Petry wants to rehabilitate controversial term,” Deutsche Welle, September 11, 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/afd-co-chair-petry-wants-to-rehabilitate-controversial-term/a-19543222;

“AntiSemitism,” U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed November 28, 2018, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitism;

Guy Tourlamain, “Introduction” in “Völkisch” Writers and National Socialism: A Study of Right-Wing Political Culture in Germany, 1890-1960 (Bern: Peter Lang AG, 2014), 24-26, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2t4f2g.5.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.