The U.N.’s Knowledge Sharing Platform is a Farce

Tech Against Terrorism’s Knowledge Sharing Platform (KSP), unveiled November 29 at the United Nations headquarters in New York City, was billed as an effort to provide practical advice to help tech companies and startups combat terrorists’ and extremists’ misuse of their technologies while respecting human rights. Unfortunately, it appears that the new platform lacks seriousness and depth and may have been designed to provide U.N.-sanctioned cover for the tech industry.

Tech Against Terrorism is a project implemented by the ICT4Peace Foundation pursuant to U.N. Security Council resolution 2354 (2017) and the U.N. Counter-Terrorism Committee Comprehensive International Framework to Counter Terrorist Narratives (S/2017/375). As part of its U.N. mandate, Tech Against Terrorism works to bridge the gap between large and small tech companies in terms of applying best practices and tools for removing and countering extremist material on their platforms. That effort resulted in the creation of the KSP, which lists such tools, resources, and best practice guidelines on its website, http://ksp.techagainstterrorism.org/.

Of course, Tech Against Terrorism emphasizes that its work, at the core, respects human rights and free speech. The rhetoric is commendable, but its actions suggest something else.

The first panel discussion at the KSP launch event included a representative from Weibo, China’s version of Twitter. Ms. Gu Haiyan, general counsel of the company, spoke about how Weibo monitors its online community for content and activities that could “endanger national unity, national security, or ethnic unity.” Human Rights Watch has specifically cited this language as a means for allowing the Chinese government to harm the work of foreign NGOs on issues it deems sensitive. The government is also, of course, known for holding human rights activists and attorneys in arbitrary detention, limiting freedom of expression, restricting religious practices, and failing to protect people from discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to the human rights watchdog. Weibo’s mere presence at the event therefore points to a lack of seriousness in terms of respecting human rights and free speech.

Several speakers also endorsed using the KSP as a framework for tech companies to continue to “self-regulate.” Permitting for-profit companies to self-regulate requires complete trust in the very same tech companies that have been slow to react to online harassment, the proliferation of terrorist material, and Russian election meddling. The concept of self-regulation would never be afforded to other business sectors. As for-profit entities, the tech sector is no different than the auto, chemical, oil, and financial services industries.

Discussions also mentioned the importance of transparency and accountability. But again, Tech Against Terrorism and its KSP does not seem to practice these values. Information about the KSP is available online, but exact details about what tech companies have agreed to as best policies and practices remains hidden to the general public and/or policymakers. Rather, KSP’s key materials are only available to member tech companies. Keeping these materials hidden behind locked pages is not transparent and prevents the public and policymakers from holding tech companies accountable to their promises.

Tech Against Terrorism’s KSP seems more like a process for tech companies—large and small—to publicly show their commitment to combatting online terrorist content without having to deliver on those commitments.

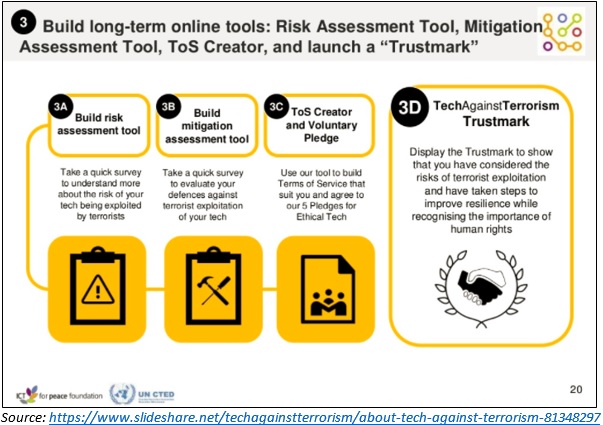

Tech companies become a member of the KSP by (1) taking a “quick survey” that is supposed to assess the risks the platform faces from terrorists’ misuse; (2) taking another “quick survey” that evaluates the companies’ means to defend itself against misuse; and (3) creating a Terms of Service that “suit” the company and taking a voluntary pledge to respect human rights and free speech. Once these steps are completed, member tech companies can proudly display the “Tech Against Terrorism Trustmark” on their website.

Quick surveys and voluntary pledges are not serious tools to help ensure tech companies are matching the online extremist threat with effective and consistent action. Indeed, the KSP seems designed as a tool to allow tech companies to acquire the U.N. imprimatur—a seal of approval that may garner some positive press and appeal to investors and advertisers. The KSP is but another example of tech companies valuing profits and reputation over substantive actions.

Stay up to date on our latest news.

Get the latest news on extremism and counter-extremism delivered to your inbox.