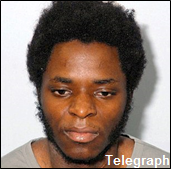

Michael Adebolajo

British domestic terrorist

Attempted foreign fighter

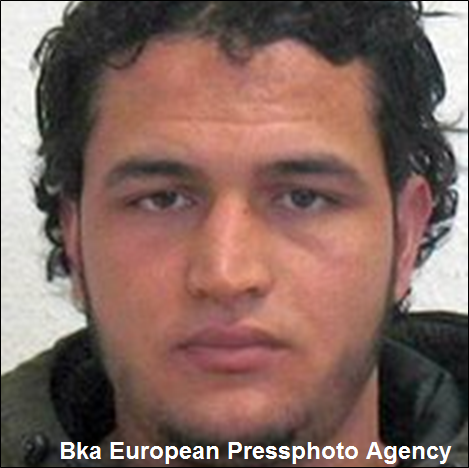

Anis Amri was a Tunisian domestic terrorist who drove a truck through a Christmas market in Berlin in December 2016, killing 12 people and wounding dozens more.“Again in the Case of the Berlin Attacker,” TIME, December 23, 2016, http://time.com/4617605/germany-police-failure-anis-amri-milan/. ISIS subsequently claimed responsibility for the attack. A video released by the ISIS-affiliated Amaq news agency showed Amri pledging allegiance to the group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, vowing “we will slaughter” the “crusaders who are shelling the Muslims every day.”“Anis Amri: Three arrested including suspect’s nephew,” CNN, December 24, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/24/europe/anis-amri-berlin-attack-milan.

On December 19, 2016, shortly after 8 p.m., Amri rammed a hijacked truck through the Christmas market in Breitscheidplatz, a public square in Berlin, Germany, before fleeing the scene. Exactly 24 hours later, ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack.“Berlin attack: timeline,” Euronews, 12/21/2016, http://www.euronews.com/2016/12/21/berlin-attack-timeline. On December 21, German police issued a warrant for Amri’s arrest with a reward of 100,000 euros for information leading to his capture. On the same day, Amri obtained a free cell phone SIM card from a company that was handing them out at a shopping mall in Nijmegen, Netherlands, close to the German-Dutch border.“Anis Amri, Suspect in the Berlin Truck Attack: What We Know,” New York Times, December 22, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/22/world/europe/anis-amri-suspect-in-the-berlin-truck-attack-what-is-known.html?_r=0. On December 22, the German federal prosecutor’s office announced that Amri’s identification card and fingerprints were found in the truck used in the attack. On December 23, at around 1 a.m. local time, Amri arrived by train at Sesto San Giovanni, a commune of Milan, Italy, where he was shot and killed in a gunfight after an Italian police officer asked him to show identification papers.“Anis Amri, Suspect in the Berlin Truck Attack: What We Know,” New York Times, December 22, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/22/world/europe/anis-amri-suspect-in-the-berlin-truck-attack-what-is-known.html?_r=0.

Amri was born in 1992 in Tataouine, central Tunisia.“Berlin truck attack: Tunisian perpetrator Anis Amri,” BBC News, December 23, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38396987. At age 14, Amri dropped out of high school and earned a reputation for drinking and partying, according to his mother.“Anis Amri: Three arrested including suspect’s nephew,” CNN, December 24, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/24/europe/anis-amri-berlin-attack-milan. In March 2011, Amri and three friends left Tunisia for the small Italian resort island of Lampedusa, south of the larger island of Sicily.“Anis Amri, Suspected Berlin Attacker, Had a History of Criminal Activity, Extremism,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/anis-amri-berlin-suspect-slipped-through-many-nets-1482444423. Upon leaving, Amri promised his family that he would earn money and send it home.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. Soon after leaving Tunisia, he was convicted in absentia by a Tunisian court for stealing a car, and sentenced to five years in prison. Amri then reached Sicily from Lampedusa and pretended to be an underage refugee, having deliberately thrown away his personal documents.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. While briefly at school in Catania, Sicily, Amri became known to police for petty theft.

While in Sicily, Amri was rejected for an Italian residency permit. In protest, he set fire to his house.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. An Italian court sentenced him to four years in prison for causing a fire, damaging property, and making threats. According to Italian prison records, Amri spent three and a half years in six different prisons across Sicily and received 12 warnings for violent and threatening behavior against both prison guards and detainees.“Anis Amri, Suspected Berlin Attacker, Had a History of Criminal Activity, Extremism,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/anis-amri-berlin-suspect-slipped-through-many-nets-1482444423;

“Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man.

In May 2015, Italian authorities released Amri and tried to deport him to Tunisia. However, Tunisian authorities could not verify his nationality and he was instead released and asked to leave the country. Amri did not return to Tunisia.“Anis Amri, Suspected Berlin Attacker, Had a History of Criminal Activity, Extremism,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/anis-amri-berlin-suspect-slipped-through-many-nets-1482444423. Instead, he traveled to Switzerland and then, in July 2015, to Germany, where he applied for asylum claiming to be an Egyptian fleeing political persecution.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. His application was rejected because he could not prove that he was Egyptian but again he could not be deported because he had no valid personal documentation.“Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. Despite his lack of identification, Amri illegally used 14 different identities to claim welfare checks during his time in Germany, according to the head of criminal police in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.“Berlin truck attack: Tunisian perpetrator Anis Amri,” BBC News, December 23, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38516691;

Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man.

While in Germany, Amri downloaded radical Islamic extremist content online. Amri also contacted Abu Walaa, a radical Salafist preacher and Iraqi ISIS supporter known colloquially as the “preacher without a face,” who was arrested in November 2016. Amri was also in contact with “Hasan C,” a known Turkish Islamic fundamentalist, and “Boban S,” a hate preacher from Dortmund, both of whom were known to radicalize young Muslims.“Anis Amri, Suspected Berlin Attacker, Had a History of Criminal Activity, Extremism,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/anis-amri-berlin-suspect-slipped-through-many-nets-1482444423. An investigation into Abu Walaa revealed that members of the Abu Walaa network discussed driving a truck full of gasoline with a bomb into a crowd.“Anis Amri: Three arrested including suspect’s nephew,” CNN, December 24, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/24/europe/anis-amri-berlin-attack-milan.

In March 2016, authorities in Berlin opened a file on Amri following indications from federal German intelligence agencies that he was a likely threat to public safety. Undercover surveillance and electronic monitoring convinced authorities that he was dealing drugs and researching bomb-making techniques online.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. According to phone records of Salafist preachers being monitored by German authorities, Amri is also believed to have offered himself as a suicide bomber, but the message was so heavily encrypted that police were unable to use it as evidence to issue an arrest warrant.Anis Amri: from young drifter to Europe’s most wanted man,” Guardian (London), December 23, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/23/anis-amri-from-young-drifter-to-europes-most-wanted-man. Despite seven separate investigations, German authorities could not agree on whether Amri was likely to commit a terrorist attack and in September 2016. Investigations after the attack revealed that Amri had used Telegram, an encrypted messaging application, employing code words to describe his plans to carry out an attack.“German police predicted Berlin attack nine months prior,” December 26, 2016,, http://www.dw.com/en/german-police-predicted-berlin-terror-attack-nine-months-prior/a-38123750.

According to an April 2019 report in Der Spiegel, investigations in Germany, France, and Belgium revealed that Amri was part of a European-wide network of ISIS supporters. The network maintained close relationships with the perpetrators of the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris. The report also details that Amri plotted with other jihadists to carry out terrorist attacks, and communicated with four ISIS fighters in Libya prior to the Christmas market attack in Berlin.“Anis Amri war offenbar Teil eines europaweiten Terror-Netzwerks,” Märkische Allgemeine, April 19, 2019, http://www.maz-online.de/Nachrichten/Politik/Weihnachtsmarkt-Attentaeter-Anis-Amri-war-offenbar-Teil-eines-europaweit-agierenden-Terror-Netzwerks.

Michael Oluwatobi Adebowale is a British-Nigerian convert to Islam and convicted terrorist who, together with Michael Adebolajo, carried out the beheading of Fusilier Lee Rigby near Rigby’s barracks in Woolwich, southeast London, on May 22, 2013. Adebowale was sentenced to a minimum of 45 years in jail after being found guilty by a British court in February 2015.Mr. Justice Sweeney, “Sentencing remarks of Mr. Justice Sweeney,” Judiciary of England and Wales, February 26, 2014, https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/JCO/Documents/Judgments/adebolajo-adebowale-sentencing-remarks.pdf. Adebowale is believed to have been inspired in part by Anwar al-Awlaki, the al-Qaeda cleric who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Yemen in 2011.Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya.

Five months before the murder, Adebowale expressed on his Facebook account his “intent to murder a soldier in the most graphic and emotive manner…”Peter Dominiczak, Tom Whitehead, Martin Evans, and Gordon Rayner, “Facebook could have prevented Lee Rigby’s murder,” Telegraph (London), November 26, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11253518/Facebook-could-have-prevented-Lee-Rigby-murder.html. In a 2014 investigation, the U.K. Parliament’s intelligence and security committee (ISC) criticized Facebook for its lack of vigilance.Vikram Dodd, Ewen MacAskill, and Patrick Wintour, “Lee Rigby murder: Facebook could have picked up killers message – report,” Guardian (London), November 26, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/nov/25/lee-rigby-murder-internet-firm-could-have-picked-up-killers-message-report-says. The ISC report noted that Facebook had shut down Adebowale’s account because he had discussed terrorism, but failed to pass on any information to British authorities.Peter Dominiczak, Tom Whitehead, Martin Evans, and Gordon Rayner, “Facebook could have prevented Lee Rigby’s murder,” Telegraph (London), November 26, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11253518/Facebook-could-have-prevented-Lee-Rigby-murder.html. According to an officer of Government Communications Headquarters (GCQH), the British intelligence apparatus responsible for providing signals intelligence, Facebook did not pick up Adebowale’s specific threat to kill a soldier because “[t]hat didn’t meet their criteria [for closure].”Peter Dominiczak, Tom Whitehead, Martin Evans, and Gordon Rayner, “Facebook could have prevented Lee Rigby’s murder,” Telegraph (London), November 26, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/11253518/Facebook-could-have-prevented-Lee-Rigby-murder.html. ISC Chairman Malcolm Rifkind added, “This company [Facebook] does not regard themselves as under any obligation to ensure that they identify such threats, or to report them to the authorities. We find this unacceptable: however unintentionally, they are providing a safe haven for terrorists.”Vikram Dodd, Ewen MacAskill, and Patrick Wintour, “Lee Rigby murder: Facebook could have picked up killers message – report,” Guardian (London), November 26, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/nov/25/lee-rigby-murder-internet-firm-could-have-picked-up-killers-message-report-says.

On the morning of May 22, 2013, Adebowale and Adebolajo decided to kill the first soldier they encountered in the name of their radical Islamist agenda. After seeing Fusilier Lee Rigby wearing a “Help For Heroes” sweater, they ran him over in their Vauxhall Tigris car. While Rigby lay prone and stunned on the floor, Adebolajo attempted to decapitate the soldier, and Adebowale stabbed him with a meat cleaver repeatedly and “with severe force” in the torso, according to the presiding judge.Mr. Justice Sweeney, “Sentencing remarks of Mr. Justice Sweeney,” Judiciary of England and Wales, February 26, 2014, https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/JCO/Documents/Judgments/adebolajo-adebowale-sentencing-remarks.pdf;

Tom Whitehead, “Drummer Lee Rigby was ‘Hacked like a Joint of Meat’ in ‘Barbarous and Cowardly Killing’, Court Hears,” Telegraph (London), November 29, 2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/terrorism-in-the-uk/10485460/Drummer-Lee-Rigby-was-hacked-like-a-joint-of-meat-in-barbarous-and-cowardly-killing-court-hears.html. Adebolajo then talked into the smartphone camera of a passing pedestrian to justify the murder.Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya. Once the police arrived at the scene, Adebowale brandished a gun and a knife and pointed the gun at the officers, who shot at Adebowale and hit his thumb.Mr. Justice Sweeney, “Sentencing remarks of Mr. Justice Sweeney,” Judiciary of England and Wales, February 26, 2014, https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/JCO/Documents/Judgments/adebolajo-adebowale-sentencing-remarks.pdf;

Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya. Effectively neutralized, Adebowale was arrested and taken into custody.Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya.

Adebowale was known to British authorities prior to the murder of Lee Rigby. In 2008, a British court sentenced Adebowale to 15 months in prison for dealing drugs to his predominantly Somali gang known as the Woolwich Boys.Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian, December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya;

Paul Peachey, Jonathan Brown, Kim Sengupta, “Lee Rigby murder: How killers Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale became ultra-violent radicals,” Independent (London): December 19, 2013, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/lee-rigby-murder-how-killers-michael-adebolajo-and-michael-adebowale-became-ultra-violent-radicals-9015743.html. Adebowale is believed to have converted from Christianity to Islam in or around 2009.Mr. Justice Sweeney, “Sentencing remarks of Mr. Justice Sweeney,” Judiciary of England and Wales, February 26, 2014, https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/JCO/Documents/Judgments/adebolajo-adebowale-sentencing-remarks.pdf;

Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya. He reportedly attended rallies held by successor groups to al-Muhajiroun—an Islamist organization founded by Anjem Choudary and Omar Bakri Muhammad—including one outside the U.S. embassy in London in September 2012.Vikram Dodd and Daniel Howden, “Woolwich murder: what drove two men to kill a soldier in the street?” Guardian (London), December 19, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/dec/19/woolwich-murder-soldier-street-adebolajo-radicalised-kenya.

In or around April 2017, Adebowale was transferred from the category “A” prison at Wakefield to the high-security psychiatric hospital at Broadmoor, a “softer” facility that costs five times more money per prisoner to operate, because he was refusing to accept medical treatment at Wakefield.Fiona Simpson, “Lee Rigby killer Michael Adebowale moved from high-security prison to ‘softer’ Broadmoor,” Evening Standard (London), April 5, 2017, http://www.standard.co.uk/news/crime/lee-rigby-killer-michael-adebowale-moved-from-highsecurity-prison-to-softer-broadmoor-a3507591.html. On April 30, 2019, Adebowale requested to be transferred to Kirikiri jail in Lagos, Nigeria.Ross McGuinness, “Lee Rigby killer Michael Adebowale ‘wants prison transfer to serve life sentence in Nigerian jail’,” Yahoo News, April 30, 2019, https://uk.news.yahoo.com/lee-rigby-killer-michael-adebowale-wants-prison-transfer-to-serve-life-sentence-in-nigerian-jail-065607092.html.

In January 2021, Adebowale was hospitalized after he contracted COVID-19.“Lee Rigby killer Michael Adebowale in hospital with Covid-19,” BBC News, January 25, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-55794995. He returned to Broadmoor in February 2021.Tom Wells, “Lee Rigby’s killer Michael Adebowale, 29, back in Broadmoor after battling Covid in hospital,” Sun, February 2, 2021, https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/uknews/13925813/lee-rigby-killer-michael-adebowale-covid-hospital/.

Sentenced to 45 years in prison for killing British soldier Lee Rigby in May 2013. His partner in the attack was Michael Adebolajo.

Lectures by now-deceased AQAP recruiter Anwar al-Awlaki were found at his address.

Carried out the beheading of Fusilier Lee Rigby with Michael Adebolajo in Woolwich, southeast London, on May 22, 2013. Sentenced to a minimum of 45 years in prison after being found guilty by a British court in February 2014.

Reportedly attended rallies held by successor groups to al-Muhajiroun, including one outside the U.S. embassy in London in September 2012.

British domestic terrorist

Attempted foreign fighter

Germaine Lindsay was a Jamaican-born suicide bomber in the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings.“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, June 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. He was a member of the four-person al-Qaeda-linked terror cell responsible for the attack, which included British citizens Shehzad Tanweer, Hasib Hussain, and Mohammad Sidique Khan.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598;

“The bombers,” BBC News, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/spl/hi/uk/05/london_blasts/investigation/html/bombers.stm. The men targeted the London Underground transit system and a double-decker bus, collectively killing 52 people and injuring over 770 others.“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, June 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. Alone, Lindsay killed 26 and injured 340 of those victims.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 17, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the bombings in a video released in September 2005.Alan Cowell, “Al Jazeera Video Links London Bombings to Al Qaeda,” New York Times, September 2, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/02/world/europe/al-jazeera-video-links-london-bombings-to-al-qaeda.html?_r=0.

Lindsay was born in Jamaica in 1985 and moved with his mother to Huddersfield, England, when he was one year old.Audrey Gillan, Ian Cobain, and Hugh Muir, “Jamaican-born convert to Islam ‘coordinated fellow bombers’,” Guardian (London), July 16, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/16/july7.uksecurity6. He attended local schools and was known among his peers as a popular, clever, artistic, musical, and sporty student.Audrey Gillan, Ian Cobain, and Hugh Muir, “Jamaican-born convert to Islam ‘coordinated fellow bombers’,” Guardian (London), July 16, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/16/july7.uksecurity6. As a teenager, Lindsay took up kickboxing and martial arts.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 17, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

Lindsay converted to Islam in 2000 at the approximate age of 15, becoming fluent in Arabic and committing long passages of the Quran to memory. Soon after his conversion, Lindsay was disciplined by his high school for distributing leaflets in support of al-Qaeda on the school’s campus.Audrey Gillan, Ian Cobain, and Hugh Muir, “Jamaican-born convert to Islam ‘coordinated fellow bombers’,” Guardian (London), July 16, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/16/july7.uksecurity6;

“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 18, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. He is believed to have been influenced by the internationally-banned Jamaican preacher Abdullah Faisal. According to the U.K. Home Office’s report on the 7/7 bombings, Lindsay attended at least one lecture given by Faisal and also listened to recordings of his lectures.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 18, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. Faisal, based in Jamaica, is the leader of Authentic Tauheed, a radical organization aligned with ISIS.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 18, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

Lindsay became a close associate of Mohammad Sidique Khan, the future mastermind of the 7/7 bombings, at some point in late 2004. The men moved in the same Islamic circles in the towns of Dewsbury and Huddersfield.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 18, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

On July 7, 2005, Lindsay was met by Khan, Tanweer, and Hasib Hussain in Luton, England. The four men arrived in London’s King’s Cross railway station by train, where they dispersed and detonated their devices in the underground ‘tube’ and on a double-decker bus.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598. At just before 9 a.m., Lindsay detonated his bomb on a southbound Piccadilly line train after leaving King’s Cross underground station, killing 26 people. After the attack, Police discovered a 9mm handgun in Lindsay’s red Fiat Brava car at Luton train station.Audrey Gillan, Ian Cobain, and Hugh Muir, “Jamaican-born convert to Islam ‘coordinated fellow bombers’,” Guardian (London), July 16, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/16/july7.uksecurity6;

“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 10, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

Domestic terrorist: One of four suicide bombers who attacked London on July 7, 2005, on behalf of al-Qaeda. Killed 26 people and wounded 340.

According to the British Home Office, Faisal “strongly influenced” Lindsay, who attended at least one Faisal lecture and listened to recordings of others.

Jamaican-born suicide bomber and member of the four-person al-Qaeda-linked terror cell in the coordinated London Underground bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings. Other members of the cell included British citizens Shehzad Tanweer, Hasib Hussain, and Mohammad Sidique Khan. The attack killed 52 people and injured over 770 others. Alone, Lindsay killed 26 and injured 340 of those victims.

Former member of al-Muhajiroun. Choudary refused to condemn the bombers. One year after the 7/7 bombings, Choudary said Muslims in Britain had the right to defend themselves from oppression using any means.

Hasib Hussain was one of four suicide bombers in the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings.“7 July London Bombings: What Happened that Day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598;

“7/7 London bombings: What Happened on 7 July 2005?” BBC, July 6, 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/33401669. At 18 years old, Hussain was the youngest member of the al-Qaeda-linked terror cell responsible for the attack, which included 7/7 bombers Mohammad Sidique Khan, Germaine Lindsay, and Shehzad Tanweer. Hussain carried out his suicide bomb attack on a double-decker bus in London’s Tavistock Square, killing 13 people.“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html;

“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated July 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. In total, the 7/7 bombings constituted the deadliest modern terrorist attack on British soil, collectively killing 52 people and wounding more than 770 others.Laura Smith-Spark, “7/7 Anniversary: UK Remembers Those Lost in 2005 London Terror Attacks,” CNN, July 9, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/07/europe/uk-london-terror-attack-anniversary/;

“7/7 London bombings: What Happened on 7 July 2005?” BBC News, July 6, 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/33401669. Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the bombings in a video released in September 2005.Alan Cowell, “Al Jazeera Video Links London Bombings to Al Qaeda,” New York Times, September 2, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/02/world/europe/al-jazeera-video-links-london-bombings-to-al-qaeda.html?_r=0.

Hussain was the youngest of four children, born in 1986 to Pakistani immigrants and raised in Holbeck, a suburb of Leeds in West Yorkshire, England.“Profile: Hasib Hussain,” BBC News, March 2, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12621387. Hussain reportedly showed signs of extremism dating back to September 2001 when, following al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks in the United States, Hussain passed two fellow students a note, ominously saying, “You’re next.”“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html. In the subsequent years, Hussain would speak openly of his support for Islamic extremists, often referring to al-Qaeda’s 9/11 bombers as “martyrs.”“Profile: Hasib Hussain,” BBC News, March 2, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12621387. At some point in 2001, Hussain met and befriended fellow extremist Mohammad Sidique Khan at a mosque in nearby Beeston.“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html. Khan, who would later be considered the ringleader of the 7/7 terrorist cell, introduced Hussain to his network of fellow Islamic extremists, including Khan’s “right-hand man” and fellow 7/7 organizer Shehzad Tanweer.“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 30, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm;

Esther Addley, “7/7 Ringleader Tried to Convert Schoolboy to Radical Islam,” Guardian (London), February 14, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2011/feb/14/7-7-ringleader-radical-islam-inquests;

“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html.

In early 2002, Hussain and his family traveled to Saudi Arabia to perform the Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage from Mecca to Medina, and then traveled to Pakistan to visit relatives. Upon the family’s return to England, Hussain reportedly became more outwardly religious, beginning to grow a beard and don traditional Islamic dress.“Profile: Hasib Hussain,” BBC News, March 2, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12621387;

“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html. At some point following his return to the United Kingdom, someone noticed that Hussain had written “Al Qaeda - No Limits” on one of his religious school workbooks.“Profile: Hasib Hussain,” BBC News, March 2, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12621387.

By 2004, Hussain had reportedly signed on to Khan’s terrorist mission, though Khan had not yet articulated the details of any terrorist plot. Around this time, Khan also seemed to identify Hussain as a potential point of contact for fellow Islamic extremists, according to a conversation wiretapped by MI5 agents. In the months leading up to the 7/7 bombings, Hussain appeared to become more involved in plotting the attacks, renting an apartment for members of the terrorist cell in Chapeltown, Leeds.“Profile: Hasib Hussain,” BBC News, March 2, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-12621387.

On July 7, 2005, at 4:00 a.m. in the morning, Hussain, Khan, and Tanweer left Leeds for London in a rented car. The three bombers linked up with fellow bomber Germaine Lindsay around three hours later and took a train into London. The four bombers arrived at King’s Cross station at 8:23 a.m., entering the London Underground shortly thereafter. At around 8:50 a.m., Khan, Tanweer, and Lindsay detonated their bombs at Edgware Road, Aldgate, and Russell Square. Approximately one hour later, at 9:47 a.m., Hussain detonated his bomb on the upper deck of a No. 30 bus in London’s Tavistock Square, killing 13 people.“7/7 Bombings: Profiles of the Four Bombers Who Killed 52 People in the London Attacks,” Independent (London), July 6, 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/77-bombings-london-anniversary-live-profiles-of-the-four-bombers-who-killed-52-people-in-london-10369984.html;

“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, last updated July 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/; “7 July London Bombings: What Happened that Day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598.

One of four suicide bombers in the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings. Carried out his suicide bomb attack on a double-decker bus in London’s Tavistock Square, killing 13 people. Other members of the cell included Shehzad Tanweer, Mohamed Sidique Khan, and Germaine Lindsay.

Former member of al-Muhajiroun.

Shehzad Tanweer was one of four suicide bombers in the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings.“Profile: Shehzad Tanweer,” BBC News, July 6, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk/4762313.stm. He was a member of the four-person al-Qaeda-linked terror cell responsible for the attack, which included British citizens Mohammad Sidique Khan, Hasib Hussain, and Germaine Lindsay.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598. The men targeted the London Underground transit system and a double-decker bus, collectively killing 52 people and injuring over 770 others.CNN Library, “July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, June 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the bombings in a video released in September 2005.Alan Cowell, “Al Jazeera Video Links London Bombings to Al Qaeda,” New York Times, September 2, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/02/world/europe/al-jazeera-video-links-london-bombings-to-al-qaeda.html?_r=0. According to British officials, in November 2004 Tanweer traveled with Khan—later identified as the attack mastermind—to Pakistan, where the pair received explosives training at an al-Qaeda camp and recorded martyrdom videos.Rachel Williams, “Defendant ended up at Pakistan training camp ‘by accident’ jury told,” Guardian (London), April 28, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/29/july-7-trial-camps;

Nic Robertson, Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Documents give new details on al Qaeda’s London bombings,” CNN, April 30, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/04/30/world/al-qaeda-documents-london-bombings/.

Tanweer was born in Bradford, England, in 1982 to British citizens of Pakistani origin.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 13, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. As a child, he moved with his family to Beeston, on the outskirts of Leeds, where 7/7 bombers Mohammad Sidique Khan and Hasib Hussain were also raised. According to the U.K. Home Office’s report on the 7/7 bombings, Tanweer did well academically and played for the local cricket team. He became more religiously observant at age 16 or 17, according to his friends’ accounts.“Profile: Shehzad Tanweer,” BBC News, July 6, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk/4762313.stm;

“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 15, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. Between 2001 and 2003, Tanweer studied sports science at Leeds Metropolitan University where he received a Higher National Diploma—a higher education qualification in the United Kingdom.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 14, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. Tanweer then worked at his father’s fish and chips shop in Leeds and did not pursue a higher degree due to a reported lack of financial aid.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 15, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

While Tanweer worked for his father, he became more involved in local Islamic centers and is believed to have met 7/7 mastermind Mohammad Sidique Khan through Khan’s youth work in the Muslim community.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. The men’s social lives centered primarily on attending mosque, youth clubs, gyms, and an Islamic bookshop in Beeston.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 15, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. In April 2004, he received a “caution” from police for disorderly conduct, though there is little information on this incident.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 15, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. During this time, Tanweer came onto the security service’s radar during a separate surveillance operation, though authorities did not investigate him because there were “more pressing priorities at the time,” according to the Home Office’s report.“Profile: Shehzad Tanweer,” BBC News, July 6, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk/4762313.stm; Ian Cobain, Richard Norton-Taylor and Jeevan Vasagar, “MI5 decided to stop watching two suicide bombers,” Guardian (London), May 1, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/may/01/terrorism.politics2.

Tanweer and Khan traveled to Pakistan in November 2004, where they received explosives training from al-Qaeda operatives, according to the Home Office.“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 19, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf. Pakistan-based Rashid Rauf—an al-Qaeda recruiter and British citizen of Kashmiri descent—arranged for Tanweer and Khan to train in a rented house in Islamabad, where they filmed martyrdom videos to be released after their deaths.Nic Robertson, Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Documents give new details on al Qaeda’s London bombings,” CNN, April 30, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/04/30/world/al-qaeda-documents-london-bombings/. Tanweer reportedly told his family and friends that he had traveled to Pakistan to find a school at which to study religion and Arabic.Sandra Laville and Dilpazier Aslam, “Trophy-rich athlete who turned to jihad,” The Guardian, July 14, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/14/july7.uksecurity6;

“Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005,” United Kingdom Home Office, May 11, 2006, 19, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228837/1087.pdf.

In June 2005, Tanweer, Khan, and Germaine Lindsay met in London and carried out a reconnaissance mission, deciding which sites to attack.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. One month later, on July 7, 2005, Tanweer, Khan, and Hasib Hussain drove in a rented car from Leeds to Luton, where they met Lindsay. The men arrived by train to London’s “King’s Cross” railway station, where they dispersed and detonated their devices in the underground ‘tube’ and on a double-decker bus. Tanweer detonated his suicide bomb in the London Underground’s Circle Line Train en route to Aldgate station, killing seven people and injuring 171 more.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598;

Duncan Gardham, “Life of July 7 bomber Shehzad Tanweer celebrated by family in Pakistan,” Telegraph (London), July 7, 2008, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2264298/Life-of-July-7-bomber-Shehzad-Tanweer-celebrated-by-family-in-Pakistan.html.

On July 6, 2006, on the eve of the first anniversary of the bombings, al-Qaeda released Tanweer’s martyrdom video on an Islamist website. The video included statements from then-al-Qaeda-deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri and American-born al-Qaeda propagandist Adam Gadahn. In his martyrdom video, Tanweer issued a warning to the west, saying, “What you have witnessed now is only the beginning of a string of attacks that will continue and become stronger.” According to British police, the timing of the release coincided with the anniversary of the 7/7 bombings to cause “maximum hurt.”“Video of 7 July bomber released,” BBC News, July 6, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/5154714.stm.

One of four suicide bombers in the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings. Other members of the cell included Mohamed Sidique Khan, Hasib Hussain, and Germaine Lindsay. The men targeted the London Underground transit system and a double-decker bus, collectively killing 52 people and injuring over 770 others. Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for the bombings in a video released in September 2005.

Member of al-Muhajiroun. Choudary refused to condemn the bombers. One year after the 7/7 bombings, Choudary said Muslims in Britain had the right to defend themselves from oppression using any means.

Mohammad Sidique Khan was the British-born mastermind of the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings.Sandra Laville and Dilpazier Aslam, “Mentor to the young and vulnerable,” Guardian (London), July 14, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/14/july7.uksecurity5;

“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, June 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. Khan himself was one of four suicide bombers who targeted the London Underground transit system and a double-decker bus, collectively killing 52 people and injuring over 770 others.“July 7 2005 London Bombings Fast Facts,” CNN, June 29, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/world/europe/july-7-2005-london-bombings-fast-facts/. He carried out the bombings alongside British nationals Shehzad Tanweer, Hasib Hussain, and Germaine Lindsay.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598. The attack constitutes the deadliest modern terrorist attack on British soil.Laura Smith-Spark, “7/7 Anniversary: UK Remembers Those Lost in 2005 London Terror Attacks,” CNN, July 9, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/07/europe/uk-london-terror-attack-anniversary/;

“7/7 London bombings: What Happened on 7 July 2005?” BBC, July 6, 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/33401669.

According to the British government, starting in 2001 Khan traveled to Pakistan several times to receive training from al-Qaeda militants.Rachel Williams, “Defendant ended up at Pakistan training camp ‘by accident’ jury told,” Guardian (London), April 28, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/29/july-7-trial-camps. He made his final trip to Pakistan months before the 7/7 bombings, bringing fellow bomber Shehzad Tanweer. At an al-Qaeda safehouse in Islamabad, the pair received explosives training and recorded martyrdom videos.Rachel Williams, “Defendant ended up at Pakistan training camp ‘by accident’ jury told,” Guardian (London), April 28, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/29/july-7-trial-camps. In September 2005, al-Qaeda released a video claiming responsibility for the 7/7 bombings. The video included a statement from then-al-Qaeda-deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri and a clip from Khan’s martyrdom video in which Khan stated, “Our words are dead until we give them life with our blood.”“‘UK Bomber’ on Al Jazeera Tape,” CNN, September 2, 2005, http://www.cnn.com/2005/WORLD/europe/09/01/london.claim/.

Khan was the son of Muslim Pakistani immigrants and the youngest of six children.“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 20, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm. He was raised in Leeds, where he met two of the 7/7 bombers, Shehzad Tanweer and Hasib Hussain.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. According to his brother, Khan adopted a more extreme version of Islam in or around 1999.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. In the early 2000s, Khan began work as a teacher’s assistant at a primary school, and served as a youth mentor in local mosques and Islamic centers.Sandra Laville and Dilpazier Aslam, “Mentor to the young and vulnerable,” Guardian (London), July 14, 2005, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jul/14/july7.uksecurity5;

“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 20, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm. Khan reportedly told his work colleagues that he had turned to religion after fighting, drinking, and using drugs as a youth.“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 20, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm.

During the early 2000s, Khan traveled to Pakistan several times to receive training from al-Qaeda militants. He also communicated with and plotted alongside al-Qaeda extremists within the United Kingdom, according to the British prosecutors.Rachel Williams, “Defendant ended up at Pakistan training camp ‘by accident’ jury told,” Guardian (London), April 28, 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2009/apr/29/july-7-trial-camps. In the summer of 2001, Khan reportedly began helping two London-based al-Qaeda operatives—Omar Sharif and Asif Hanif—to recruit British youth for training in Afghanistan. Sharif and Hanif would go on to perpetrate suicide attacks in Tel Aviv, Israel, in 2003.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. Khan was reportedly also in contact with U.K.-based Mohammed Quayyum Khan, a suspected al-Qaeda operative.Shiv Malik, “My brother the bomber,” Prospect (London), June 30, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/my-brother-the-bomber-mohammad-sidique-khan. British prosecutors later accused Mohammed Quayyum Khan of facilitating Mohammad Siddiqe Khan’s 2003 travel to Pakistan.Ian Cobain and Jeevan Vasagar, “Free – the man accused of being an al-Qaeda leader, aka ‘Q’,” Guardian (London), May 1, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2007/may/01/politics.topstories3.

Khan was dismissed from his job in 2004 due to poor attendance, evidently because he had traveled to and spent extended periods of time in Pakistan. The MI5 monitored Khan on four separate occasions between February and March of 2004. Authorities suspected that Khan was associated with a domestic group planning to build a fertilizer bomb, though they stopped monitoring him due to a lack of evidence.“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 20, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm. In November of that year, Khan again traveled to Pakistan, this time accompanied by Shehzad Tanweer.“Profile: Mohammad Sidique Khan,” BBC News, April 20, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4762209.stm. Pakistan-based Rashid Rauf—an al-Qaeda recruiter and British citizen of Kashmiri descent—arranged for Tanweer and Khan to stay in a rented house in Islamabad, where they received explosives training and filmed martyrdom videos to be released after their deaths.Nic Robertson, Paul Cruickshank and Tim Lister, “Documents give new details on al Qaeda’s London bombings,” CNN, April 30, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/04/30/world/al-qaeda-documents-london-bombings/.

On July 7, 2005, Khan, Tanweer, and Hasib Hussain drove in a rented car from Leeds to Luton, where they met Lindsay. The men arrived by train to London’s “King’s Cross” railway station, where they dispersed and detonated their devices in the underground ‘tube’ and on a double-decker bus. Khan detonated his suicide bomb in the tube’s Circle Line Train at the Edgeware Road stop, killing six people.“7 July London bombings: What happened that day?” BBC News, July 3, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-33253598.

British-born mastermind of the coordinated London bombings on July 7, 2005, known colloquially as the 7/7 bombings. Khan himself was one of four suicide bombers who targeted the London Underground transit system and a double-decker bus, collectively killing 52 people and injuring over 770 others. Other members of the cell included Shehzad Tanweer, Hasib Hussain, and Germaine Lindsay.

Reportedly attended al-Muhajiroun training camps in Pakistan. Choudary refused to condemn the bombers. Allegedly used al-Muhajiroun safe houses before the attack. One year after the 7/7 bombings, Choudary said Muslims in Britain had the right to defend themselves from oppression using any means.

French-born Mehdi Nemmouche is a former ISIS fighter responsible for murdering four people at the Jewish Museum in Brussels on May 24, 2014. The attack was reportedly the first in Europe by a returned foreign fighter from Syria.Agence France-Presse, “Frenchman convicted over deadly attack at Brussels Jewish museum,” Times of Israel, March 7, 2019, https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog-march-7-2019/. Prior to the attack, Nemmouche spent a year fighting alongside ISIS in Syria and guarding the group’s U.S. and European hostages in Aleppo. Among these hostages were U.S. citizens James Foley and Steven Sotloff, both of whom were beheaded by the militants in late 2014.“Brussels Jewish Museum killings: Suspect ‘admitted attack’,” BBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27654505;

“Mehdi Nemmouche, Brussels Jewish Museum shooting suspect, arrested,” CBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/mehdi-nemmouche-brussels-jewish-museum-shooting-suspect-arrested-1.2661011;

Christopher Dickey, “French Jihadi Mehdi Nemmouche Is the Shape of Terror to Come,” Daily Beast, September 9, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/09/09/the-face-of-isis-terror-to-come.html. On March 7, 2019, a Belgian court convicted Nemmouche on murder charges in relation to the museum shooting. He received a life sentence.“Brussels Jewish Museum murders: Mehdi Nemmouche guilty,” BBC News, March 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47490332; “Brussels Jewish Museum murders: Mehdi Nemmouche jailed for life,” BBC News, March 12, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47533533. On March 21, 2025, a French court convicted Nemmouche on charges of holding four journalists hostage in Syria. He received a life sentence.“French jihadist accused of holding journalists hostage in Syria sentenced to life in prison,” France 24, March 21, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250321-french-court-rule-jihadist-accused-holding-journalists-hostage-syria-mehdi-nemmouche.

Born to a single mother in Roubaix, France, Nemmouche was raised primarily by his grandmother before being placed in a family home. Between the ages of 13 and 22, Nemmouche accumulated 22 criminal offenses, including vehicle theft, assaults, and armed robbery. During this period, Nemmouche completed schooling at a technical institute, but failed to pass his professional licensing test to become a licensed electrician.“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html.

In 2007, at 22 years old, Nemmouche was convicted of robbery. He was later convicted for aggravated theft 2008 and 2009, while already in custody. While serving a five-year prison sentence, Nemmouche allegedly associated with Islamist inmates and began to adopt a radical interpretation of Islam. In 2011, while still imprisoned, Nemmouche attacked a prison supervisor, for which he was prosecuted. Nemmouche was ultimately released from prison on December 4, 2012.“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html;

“Brussels Jewish Museum killings: Suspect ‘admitted attack’,” BBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27654505.

Later that month, Nemmouche left France to join ISIS abroad, traveling through Brussels, London, and Istanbul before entering into Syria.“Mehdi Nemmouche, Brussels Jewish Museum shooting suspect, arrested,” CBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/mehdi-nemmouche-brussels-jewish-museum-shooting-suspect-arrested-1.2661011;

“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html. Upon joining ISIS, Nemmouche was assigned to guard an ISIS detention facility in Aleppo holding European hostages including French journalists Didier François, Nicolas Hénin, Eduard Elias, and Pierre Torres.“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html. Nemmouche also allegedly guarded hostages James Foley and Steven Sotloff, who were executed by the militant group in mid-2014.Christopher Dickey, “French Jihadi Mehdi Nemmouche Is the Shape of Terror to Come,” Daily Beast, September 9, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/09/09/the-face-of-isis-terror-to-come.html.

According to former ISIS hostage Nicolas Hénin, Nemmouche would regularly beat and torture prisoners. Hénin said that Nemmouche had once bragged about raping a woman before cutting her throat and beheading her baby.Christopher Dickey, “French Jihadi Mehdi Nemmouche Is the Shape of Terror to Come,” Daily Beast, September 9, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/09/09/the-face-of-isis-terror-to-come.html. “It’s such a pleasure to cut off a baby’s head,” Hénin quoted Nemmouche as saying.David Chazan, “Brussels museum shooting suspect ‘beheaded baby’,” Telegram (London), September 7, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/11080079/Brussels-museum-shooting-suspect-beheaded-baby.html. According to several former ISIS hostages, Nemmouche was nicknamed “Abu Omar the Hitter” because of the way in which he would violently beat prisoners.“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html;

Christopher Dickey, “French Jihadi Mehdi Nemmouche Is the Shape of Terror to Come,” Daily Beast, September 9, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/09/09/the-face-of-isis-terror-to-come.html. Hénin said that Nemmouche also boasted to ISIS hostages about his intention to carry out a terrorist attack during Paris’s July 14 Bastille Day parade.Christopher Dickey, “French Jihadi Mehdi Nemmouche Is the Shape of Terror to Come,” Daily Beast, September 9, 2014, http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/09/09/the-face-of-isis-terror-to-come.html.

Nemmouche returned from Syria to France in March 2014 and traveled to Brussels several weeks later. On May 24, 2014, Nemmouche stormed into the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels, killing four people.“Mehdi Nemmouche: ce que l’on sait de son parcours,” Le Monde (Paris), August 9, 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2014/09/08/mehdi-nemmouche-ce-que-l-on-sait-de-son-parcours_4483458_3224.html. Nemmouche immediately fled the scene and later boarded a bus from Amsterdam heading to France’s southern port city of Marseille. On May 30, 2014, French authorities conducting customs inspections found and detained Nemmouche at the Saint-Charles transit station in Marseille. Authorities confiscated a video recording of Nemmouche claiming responsibility for the Jewish Museum attack. Authorities also seized the two guns used in the museum attack and a white sheet decorated with ISIS’s symbol.“Mehdi Nemmouche, Brussels Jewish Museum shooting suspect, arrested,” CBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/mehdi-nemmouche-brussels-jewish-museum-shooting-suspect-arrested-1.2661011;

“Brussels Jewish Museum killings: Suspect ‘admitted attack’,” BBC News, June 1, 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27654505.

On July 30, 2014, Nemmouche was charged with murder in a terrorist context by Belgian courts.Frances Robinson, “French Suspect in Brussels Jewish Museum Killings Charged,” Wall Street Journal, July 30, 2014, https://www.wsj.com/articles/french-suspect-in-brussels-jewish-museum-killings-charged-1406725425. On November 3, 2016, Belgium prosecutors decided that Nemmouche would be extradited to France once Belgium “no longer needs him” to face additional charges there.“Suspect in Brussels Jewish museum shooting faces extradition to France,” France24, November 3, 2016, http://www.france24.com/en/20161103-belgium-extradition-france-brussels-jewish-museum-shooting-nemmouche. French authorities are investigating Nemmouche’s participation in the ISIS kidnapping of the four French journalists held hostage in Syria in 2014.“Suspect in Brussels Jewish museum shooting faces extradition to France,” France24, November 3, 2016, http://www.france24.com/en/20161103-belgium-extradition-france-brussels-jewish-museum-shooting-nemmouche.

Nemmouche went on trial in Brussels on January 10, 2019.“Brussels Nemmouche trial: Suspect claims he was ‘tricked,’” BBC News, March 5, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47454870. During the trial, Hénin testified that he had no doubt Nemmouche was one of his guards and described Nemmouche as “sadistic, playful and narcissistic.”“Brussels Jewish Museum murders: Mehdi Nemmouche guilty,” BBC News, March 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47490332. Nemmouche’s attorney protested that his client was on trial only for the museum shooting. In regard to the museum attack, Nemmouche’s attorney alleged that Iranian or Lebanese intelligence had recruited Nemmouche to join ISIS and that he was acting in his capacity as a double agent while he was guarding the French journalists. Nemmouche’s lawyer argued further that the Brussels attack was actually a “targeted execution of Mossad agents” carried out by an unknown person. The court found no links to the Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence agency.“Brussels Jewish Museum murders: Mehdi Nemmouche guilty,” BBC News, March 7, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47490332.

On March 7, 2019, a Belgian court convicted Nemmouche for the murder of four people during the museum attack. The court also convicted Nacer Bendrer on a murder charge for helping Nemmouche plan the attack and providing the weapons. Nemmouche received a life sentence on March 12, 2019. Bendrer received a sentence of 15 years in prison. In May 2019, Belgian authorities transferred Nemmouche to Paris for questioning over his suspected role in the kidnapping of four journalists in Syria in 2013.“Jewish museum attacker Nemmouche questioned in France over Syria kidnappings,” France 24, May 17, 2019, https://www.france24.com/en/20190517-belgium-museum-killer-nemmouche-france-over-2013-syria-kidnappings..span> On October 22, 2019, the Brussels criminal court ordered Nemmouche and Bendrer to pay a total of €985,000, without taxes, to the families of the four victims.“Jewish Museum terrorists ordered to pay nearly €1 million in victim compensation,” Brussels Times, October 22, 2019, https://www.brusselstimes.com/all-news/belgium-all-news/74818/jewish-museum-terrorists-ordered-to-pay-nearly-e1-million-in-victim-compensation-mehdi-nemmouche-nacer-bendrer-terrorist-attacks/.

ISIS kidnapped journalists Didier Francois, Edouard Elias, Nicolas Henin, and Pierre Torres in June 2013. They were released in April 2014.“French jihadist accused of holding journalists hostage in Syria sentenced to life in prison” France 24, March 21, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250321-french-court-rule-jihadist-accused-holding-journalists-hostage-syria-mehdi-nemmouche. On February 17, 2025, Nemmouch and four other accused jihadists—Kais Al Abdallah, Abdelmalek Tanem, Salim Benghalem, and Oussama Atar—went on trial for holding the journalists hostage. Benghalem and Atar were tried in absentia as they were presumed dead. While Nemmouche remained silent through his trial in Belgium, he began his Paris trial by denying that he had ever imprisoned any hostages.“France trial opens for suspected IS group militants accused of kidnapping journalists in Syria,” France 24, February 17, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250217-france-tries-five-for-kidnapping-journalists-in-syria. In a September 2014 magazine article, Henin recalled Nemmouche punching him in the face. During the 2025 trial, the four journalists each identified Nemmouche as their captor. Henin testified that he witnessed Nemmouche carry out mock executions and torture other captives. Nemmouche admitted during the trial that he had been an ISIS fighter, but he fought against only the forces of Syria’s former dictator Bashar al-Assad. He admitted to joining al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria and then ISIS, admitting he “was a terrorist” and would “never apologise for that.”“French jihadist accused of holding journalists hostage in Syria sentenced to life in prison,” France 24, March 21, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250321-french-court-rule-jihadist-accused-holding-journalists-hostage-syria-mehdi-nemmouche. On March 21, 2025, the court found Nemmouche and the other four accused jihadists guilty of holding the journalists hostage. The court sentenced Nemmouche to life in prison with a minimum of 22 years without parole. Abdallah received a 20-year sentence. Tanem received a 22-year sentence. The presumed deceased Benghalem and Atar both received life sentences.“French jihadist accused of holding journalists hostage in Syria sentenced to life in prison,” France 24, March 21, 2025, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250321-french-court-rule-jihadist-accused-holding-journalists-hostage-syria-mehdi-nemmouche.

Khalid Masood, born Adrian Russell Elms, was a British domestic terrorist who killed four people in a car-ramming and stabbing attack in London on March 22, 2017. Masood was shot and killed by police minutes into the attack after stabbing an unarmed police officer.“London attack: Khalid Masood identified as killer,” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39372154;

“LATEST: Man believed responsible for the terrorist attack in Westminster named,” Metropolitan Police, March 23, 2017, http://news.met.police.uk/news/update-westminster-attack-man-believed-responsible-named-230160;

Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/. The following day, ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack, describing Masood as a “soldier of the Islamic State.”Lizzie Dearden, “Isis claims responsibility for London attack that killed at least three victims,” Independent (London), March 23, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/isis-london-attack-westminster-terror-responsibility-latest-islamic-state-daesh-a7645696.html. British Prime Minister Theresa May revealed that Masood was “known” to British intelligence service MI5, but that he was a “peripheral figure” who was not part of the “current intelligence picture.”“London attack: British-born attacker 'known to MI5',” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39363297;

Dominic Casciani, “London attack: Khalid Masood - what we know about killer,” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39373766. British authorities do not believe that Masood had any ties to ISIS or other jihadist groups.Laura Smith-Spark and Carol Jordan, “London attack: Khalid Masood named as perpetrator,” CNN, March 23, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/03/23/europe/london-attack/;

Dominic Evans and Omar Fahmy, “London attack bears Islamic State ‘signature’ but no clear link,” Reuters, March 24, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-security-islamicstate-idUSKBN16V25A;

Tom Batchelor, “Khalid Masood: London attacker had no links to Isis or al-Qaeda, says Met Police,” Independent (London), March 28, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/khalid-masood-london-attack-isis-al-qaeda-no-links-police-a7652696.html. Authorities are, however, investigating Masood’s use of encrypted messaging service WhatsApp minutes before he carried out the March 22 attack.Greg Toppo, “London terror attacker used WhatsApp, the encrypted messaging app, before rampage,” USA Today, last updated March 27, 2017, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2017/03/26/london-attacker-whatsapp-message/99668890/.

Beginning in the early 1980s, Masood spent two decades in and out of prison for violent and petty crimes.“LATEST: Man believed responsible for the terrorist attack in Westminster named,” Metropolitan Police, March 23, 2017, http://news.met.police.uk/news/update-westminster-attack-man-believed-responsible-named-230160;

Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/. According to London Metropolitan police, Masood had been convicted for grievous bodily harm, weapons possession, and assault. He was first convicted in November 1983 for “criminal damage,” and his last conviction came in December 2003 for possession of a knife. He had no terrorism-related convictions.Dominic Casciani, “London attack: Khalid Masood - what we know about killer,” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39373766. Between 2005 and 2009, Masood reportedly taught English in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, to employees of the General Authority of Civil Aviation. Upon his return to England in 2009, Masood took a position as a “senior English teacher” at a TEFL college in Luton, according to his curriculum vitae.Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/. According to Masood’s employer at the time, Masood did not demonstrate any radical tendencies.Alice Ross, “London terrorist Khalid Masood showed no extremist tendencies, says ex-boss,” Guardian (London), March 28, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/mar/28/westminster-terrorist-khalid-masood-wasnt-an-islamist-says-ex-boss. Nonetheless, Masood reportedly first came to the attention of British intelligence agency MI5 upon his return from Saudi Arabia because he was “loosely connected” to other terror suspects under investigation in Luton, according to London’s Guardian.Hannah Summers, Ewen MacAskill, and Vikram Dodd, “Westminster attack: Khalid Masood identified as potential extremist in 2010,” Guardian (London), March 26, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/mar/26/westminster-attack-khalid-masood-identified-as-potential-extremist-in-2010. The agency then reportedly lost track of him.“London attack: British-born attacker 'known to MI5',” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39363297;

Hannah Summers, Ewen MacAskill, and Vikram Dodd, “Westminster attack: Khalid Masood identified as potential extremist in 2010,” Guardian (London), March 26, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/mar/26/westminster-attack-khalid-masood-identified-as-potential-extremist-in-2010.

Masood was a convert to Islam, though there is little detail on his conversion. Security and media sources speculate that he may have radicalized during his time in prison.Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/. Masood was reportedly fervently religious. An unidentified source told Sky News that Masood had prayed regularly at a mosque on Fridays.“Khalid Masood: Everything we know about 52-year-old Westminster attacker,” Sky News, March 23, 2017, http://news.sky.com/story/khalid-masood-everything-we-know-about-52-year-old-westminster-attacker-10811626.

On March 21, 2017, Masood checked into the Preston Park Hotel in Brighton. The following day, he rented an SUV and told hotel staff that he was heading to London, but the capital “isn’t like it used to be.”Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/. Upon arriving in London, Masood rammed his car into a crowd of pedestrians on London’s Westminster Bridge, killing four people and wounding more than 50 others. Masood then crashed the car into railings outside the nearby Houses of Parliament. Armed with a knife, Masood stabbed unarmed police officer Keith Palmer before being fatally shot by police.“London attack: Khalid Masood identified as killer,” BBC News, March 23, 2017, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-39372154. Palmer died from his wounds.Robert Mendick and Emily Allen, “Khalid Masood: Everything we know about the London attacker,” Telegraph (London), March 24, 2017, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/03/24/khalid-masood-everything-know-london-attacker/.

On March 23, ISIS’s Amaq News Agency claimed in a tweet that a “soldier of the Islamic State” had carried out the attack, though Amaq did not specifically name Masood.Laura Smith-Spark and Carol Jordan, “London attack: Khalid Masood named as perpetrator,” CNN, March 23, 2017, http://www.cnn.com/2017/03/23/europe/london-attack/;

Dominic Evans and Omar Fahmy, “London attack bears Islamic State ‘signature’ but no clear link,” Reuters, March 24, 2017, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-security-islamicstate-idUSKBN16V25A. Five days after the attack, British police reported that they had not discovered ties between Masood and ISIS or any other extremist group.Tom Batchelor, “Khalid Masood: London attacker had no links to Isis or al-Qaeda, says Met Police,” Independent (London), March 28, 2017, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/khalid-masood-london-attack-isis-al-qaeda-no-links-police-a7652696.html. Nonetheless, senior national coordinator for U.K. Counter Terrorism Policing Neil Basu told British media that Masood “clearly” had an “interest in jihad.” Latika Bourke, “‘I totally condemn his actions’: London attacker Khalid Masood's wife speaks out,” Sydney Morning Herald, March 29, 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/world/i-totally-condemn-his-actions-london-attacker-khalid-masoods-wife-speaks-out-20170328-gv8k4r.html.

Less than a week after the attack, British police also opened an investigation into Masood’s use of encrypted messaging service WhatsApp. Masood had reportedly sent an encrypted message to an unidentified individual minutes before the attack.Greg Toppo, “London terror attacker used WhatsApp, the encrypted messaging app, before rampage,” USA Today, last updated March 27, 2017, http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2017/03/26/london-attacker-whatsapp-message/99668890/. After the revelation that Masood used the app, British Home Secretary Amber Rudd said that authorities must have full access to encrypted messaging services so that those platforms “don’t provide a secret place for terrorists to communicate with each other.”Andrew Sparrow, “WhatsApp must be accessible to authorities, says Amber Rudd,” Guardian (London), March 26, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/mar/26/intelligence-services-access-whatsapp-amber-rudd-westminster-attack-encrypted-messaging.

One week after the attack, Masood’s wife, Rohey Hydara, issued a statement condemning her husband’s actions.Latika Bourke, “‘I totally condemn his actions’: London attacker Khalid Masood's wife speaks out,” Sydney Morning Herald, March 29, 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/world/i-totally-condemn-his-actions-london-attacker-khalid-masoods-wife-speaks-out-20170328-gv8k4r.html.

Domestic terrorist, United Kingdom: Murdered at least four people in a car-ramming and stabbing attack on March 22, 2017. ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack, calling Masood as a “soldier of the Islamic State.” British Prime Minister Theresa May revealed that Masood was long known to British intelligence service MI5, but that he was a “peripheral figure” who was not part of the “current intelligence picture.”

Converted to Islam, though specific conversion details could not be determined. Masood was born Adrian Elms. He reportedly adopted his stepfather’s surname of Ajao after his mother remarried. Masood reportedly married a Muslim woman in 2004, though it is unclear whether or not he converted around the same time. Masood had a history of violent crime, including convictions for assaults, grievous bodily harm, and possession of a knife. Masood was first convicted in 1983 for criminal damage and last convicted in December 2003 for possession of a knife. He had no convictions for terror-related offenses. Masood spent time in three different prisons, leading to speculation among media and security sources that he radicalized in one of them. From 2005 to 2009, Masood lived in Saudi Arabia teaching English to workers at the General Authority of Civil Aviation. After his return to England, Masood lived for more than two years in the English city of Luton. Convicted English cleric and ISIS supporter Anjem Choudary reportedly regularly visited the city. (No estimated age at conversion)

Born Adrian Russell Elms. Killed five people in a car-ramming and stabbing attack in London on March 22, 2017. Shot and killed by police minutes into the attack after stabbing an unarmed police officer.

Lived for several years in Crawley and Luton, England, in the early 2000s. Both cities were active al-Muhajiroun bases while Masood was there. Authorities considered Masood a person of interest because of his ties to other al-Muhajiroun members under investigation, including suicide bomber Waheed Majeed and fertilizer bomb conspirator Waheed Mahmoud.

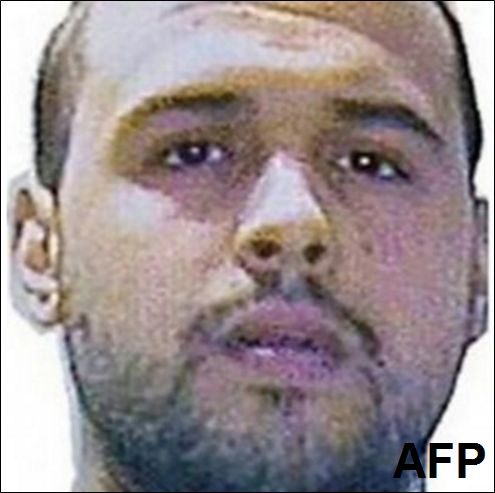

Ibrahim el-Bakraoui was one of two suicide bombers at Zaventem airport in ISIS’s March 22, 2016, coordinated bombings in Brussels, Belgium.“Brussels attacks: Two brothers behind Belgium bombings,” BBC News, March 23, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35879141. The bombings, carried out by suicide bombers at the airport and at Brussels’ Maelbeek metro station, killed a total of 32 people and injured more than 300 others.Merrit Kennedy and Camila Domonoske, “The Victims Of The Brussels Attacks: What We Know,” NPR, March 31, 2016, http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/03/26/471982262/what-we-know-about-the-victims-of-the-brussels-attack Then-29-year-old Ibrahim carried out the suicide bombing alongside Belgian citizen Najim Laachraoui. Ibrahim’s then-27-year-old brother, Khalid el-Bakraoui, was the single suicide bomber at Maelbeek station.“Brussels attacks: Two brothers behind Belgium bombings,” BBC News, March 23, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35879141. Less than one month after the attacks, ISIS claimed in its English-language magazine Dabiq that the Bakraoui brothers were organizers of both the Brussels and Paris attacks, which occurred on November 13, 2015.“The Nights of Shahadah in Belgium,” Dabiq, April 13, 2016, 6, https://azelin.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/the-islamic-state-22dacc84biq-magazine-1422.pdf. In response, Belgian terrorism expert Pieter Van Ostayen told the Wall Street Journal that he doubted the Bakraoui brothers had had the “operational knowledge” needed to organize the attacks, noting that they might have helped to “[provide] the weapons.”Valentina Pop, “Islamic State Claims Khalid and Ibrahim El-Bakraoui Were Organizers of Paris and Brussels Attacks,” Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/prosecutors-believe-raid-prompted-brussels-attacks-1460546336.

Ibrahim and his brother Khalid were born in Belgium to Moroccan parents and raised in the Brussels neighborhood of Laeken. As young men, they engaged in criminal activity including carjackings and bank robberies.“Ibrahim and Khalid el-Bakraoui: From Bank Robbers to Brussels Bombers,” New York Times, March 24, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/25/world/europe/expanding-portraits-of-brussels-bombers-ibrahim-and-khalid-el-bakraoui.html?_r=0;

Patrick J. McDonnell and Erik Kirschbaum, “Brussels suicide bombers fit familiar profile; links to Paris terrorist attacks seen,” Los Angeles Times, March 23, 2016, http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-suspect-in-brussels-attacks-is-sought-20160323-story.html. Ibrahim was arrested in January 2010 after partaking in a botched bank robbery during which he shot a police officer in the leg. That August, he was sentenced to nine years in prison for attempted murder, and is believed to have radicalized within the cell walls.Ibrahim and Khalid el-Bakraoui: From Bank Robbers to Brussels Bombers,” New York Times, March 24, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/25/world/europe/expanding-portraits-of-brussels-bombers-ibrahim-and-khalid-el-bakraoui.html?_r=0. According to a eulogy for Ibrahim published in the April 2016 issue of ISIS’s magazine Dabiq, while in prison, Ibrahim “followed the news about the atrocities against the Muslims in [Syria]. Something clicked and he decided to change his life, to live for his religion.”“The Nights of Shahadah in Belgium,” Dabiq, April 13, 2016, 6, https://azelin.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/the-islamic-state-22dacc84biq-magazine-1422.pdf;

Valentina Pop, “Islamic State Claims Khalid and Ibrahim El-Bakraoui Were Organizers of Paris and Brussels Attacks,” Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/prosecutors-believe-raid-prompted-brussels-attacks-1460546336. Ibrahim received parole in October 2014.Ibrahim and Khalid el-Bakraoui: From Bank Robbers to Brussels Bombers,” New York Times, March 24, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/25/world/europe/expanding-portraits-of-brussels-bombers-ibrahim-and-khalid-el-bakraoui.html?_r=0.