Losing Dabiq: Potholes on the Road to the Apocalypse

The small, quiet town of Dabiq, nestled in the countryside of northern Syria about 10 miles from the border with Turkey, held little military or strategic significance until 2014, when the birth and lightning conquests of ISIS placed it on the political world map.

Islamic scripture prophesizes that an apocalyptic battle will take place at Dabiq between Muslim forces and their ‘Roman’ enemies (modernized by ISIS to mean the U.S. and Western countries). ISIS, from its inception, used that apocalyptic prophesy and its prediction of a final Muslim victory to link its state-building ambitions to Islamic theological and apocalyptic traditions, and to legitimize its declaration of a caliphate.

The Dabiq prophesy and narrative became a theme in ISIS propaganda and a powerful recruitment tool in and of itself.

ISIS named its elaborate, English-language magazine after the city. The first issue alone tells the story of Dabiq twice—once at the beginning and once at the end—while each subsequent issue showcases an ominous 2004 quote on the Contents page from Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, founder of ISIS precursor group al-Qaeda in Iraq: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify—by Allah’s permission—until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.” The message is repeated in high-definition propaganda videos such as “No Respite.” Computer-generated fire balls explode behind the name of the city while the narrator gleefully tells English viewers that one day soon “…the flames of war will finally burn you on the hills of Dabiq. Bring it on!”

ISIS named its elaborate, English-language magazine after the city. The first issue alone tells the story of Dabiq twice—once at the beginning and once at the end—while each subsequent issue showcases an ominous 2004 quote on the Contents page from Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, founder of ISIS precursor group al-Qaeda in Iraq: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify—by Allah’s permission—until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.” The message is repeated in high-definition propaganda videos such as “No Respite.” Computer-generated fire balls explode behind the name of the city while the narrator gleefully tells English viewers that one day soon “…the flames of war will finally burn you on the hills of Dabiq. Bring it on!”

Dabiq was also prominently featured in video starring Mohammed Emwazi, a British citizens nicknamed “Jihadi John” who killed five Western hostages in 2014. In the video, Emwazi taunts viewers with the severed head of American aid worker Abdul-Rahman Kassig at his feet. “Here we are, burying the first American Crusader in Dabiq, eagerly waiting for the remainder of your armies to arrive,” he intones.

But ISIS’s Dabiq-centered narrative began to shift as the group began to experience significant military setbacks, such as the loss of Fallujah. Propaganda videos began to praise ISIS’s soldiers for fighting for their religion—not for human desires such as territory. To live and die for Islam out in the desert was a prize in and of itself, recruitment material claimed, and God would look favorably upon those who continued to fight for the caliphate.

In a May 2016 statement, former ISIS spokesman and head of external operations Abu Mohammed al-Adnani seemed to foreshadow the loss of Dabiq and other ISIS-held cities like Mosul and Raqqa when he claimed that ISIS did not rely on territory it controlled for its legitimacy.

On October 6, 2016, Syrian rebel forces, backed by Turkish armor and American air power, began an assault on Dabiq. For 10 days, ISIS forces attempted to hold their prized town, but on October 16, the coalition forced the last ISIS fighters out of Dabiq and retook the town.

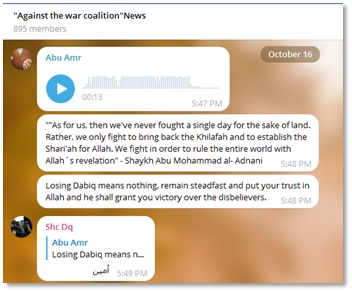

ISIS did not acknowledge the fall of Dabiq, but the loss of a town in which the group placed so much symbolic and theological value cannot help but weaken the group’s image. ISIS attempted to draw attention away from the loss of Dabiq with propaganda focused on things like providing access to potable water within its territories. Pro-ISIS chats on Telegram, an encrypted messaging application and website, contained posts telling ISIS supporters to “remain steadfast” and “put your trust in [God].”

Yet anti-ISIS mujahideen and anti-ISIS activists were quick to produce and post material mocking the terrorist group and bolstering their own recruitment. Many treated the fall of Dabiq as a decisive blow to ISIS’s standing as an Islamic authority.

One member of a pro-ISIS chat encourages trust, another responds “Amen”

Raqqa Activist Group mocks ISIS in Tweet the morning Dabiq falls

Many of the responses included a firm denial that ISIS had ever represented a true Islamic caliphate. Anti-ISIS mujahideen groups who are competing for recruits and allegiances took the loss as an opportunity to discredit ISIS and bolster their own positions as true, strong Islamic authorities.

Anti-ISIS, Pro-Jihad Channel “Fighting Journalists” mocks ISIS after loss of Dabiq

Still, even after the defeat at Dabiq, some of the Islamic State’s online supporters continue to argue that the West is operating on a compressed timeline and ISIS’s withdrawal from Dabiq has nothing to do with the prophesized battle to come.

As concerning is ISIS’s continued ability to inspire attacks in Western countries, through its misuse of the Internet and online platforms. A recent French investigation revealed that through the encrypted messaging application Telegram, one ISIS recruiter in Syria or Iraq, 29-year-old French citizen Rachid Kassim, instructed and encouraged the attack that killed a French police couple in their home, the execution of a French priest during Mass, and the attempt to detonate a car bomb near Notre Dame Cathedral.

So, while ISIS's stature and military prowess may have taken a hit with the fall of Dabiq, its ability to terrorize has yet to be significantly diminished.

Anwar Al-Awlaki: The Modern Face of Terror

On the morning of September 30, 2011, Predator drones circled thousands of feet above a remote stretch of northern Yemen, monitoring a meeting of senior al-Qaeda militants. The CIA professionals operating the drones were not taking any chances. Moments after a Hellfire missile hit the car carrying “high value targets,” another missile struck it a second time.

According to Jeremy Scahill’s account in Dirty Wars, “When villagers in the area arrived at the scene of the missile strike, they reported that the bodies inside the car had been burned beyond recognition. ... Amid the wreckage, they found a symbol more reliable than a fingerprint in Yemeni culture: the charred rhinoceros-horn handle of a jambiya dagger. There was no doubt that it belonged to Anwar al-Awlaki.”

Five years after al-Awlaki’s death, the case of the American-born radical imam who became the face of the world’s most dangerous al-Qaeda affiliate continues to stir debate over the proper use of force in the war on terror. It shouldn’t.

By the time President Obama gave the order to eliminate al-Awlaki from the battlefield, the Islamist cleric and propagandist had amassed first-hand responsibility for a catalogue of plots commissioned in the service of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Before he even left America, al-Awlaki was linked to two future Sept. 11 hijackers, Khalid al-Midhar and Nawaq Alhazmi, who prayed at his San Diego mosque and were seen in long conferences with him. Alhazmi even followed al-Awlaki to his new mosque in Virginia.

In 2009, al-Awlaki was in direct contact with Nidal Hasan before the Army psychiatrist went on a shooting rampage, killing 13 people at Fort Hood, Texas. Al-Awlaki personally directed and supplied the explosives that Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab hid in his underwear and tried to detonate on an airplane from Amsterdam to Detroit on Christmas Day, 2009. Al-Awlaki also began the al-Qaeda magazine Inspire, which includes articles like, “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom.”

Nonetheless, a chorus of critics arose to object to the “targeted assassination” of this notorious leader of external operations for al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Critics of the drone strike paint Awlaki as little more than a clerical firebrand popular on YouTube who posed no immediate danger. He wasn’t even killed on a battlefield, this argument runs, as if the U.S. government should have kept its finger off the trigger until an enemy that doesn’t wear a uniform took the field in his dress blues. Another argument posited that al-Awlaki, as a U.S. citizen, was denied due process, as if a leader of an enemy force in a unilaterally declared war against the U.S. should expect to enjoy Miranda rights.

The notion that al-Awlaki was a bit player in the jihadist movement – or that targeting him was unwarranted – is simply preposterous. AQAP was the first al-Qaeda franchise to publish in English, and, according to former U.S. Treasury Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Stuart Levey, al-Awlaki “has involved himself in every aspect of the supply chain of terrorism -- fundraising for terrorist groups, recruiting and training operatives, and planning and ordering attacks on innocents.” His summons to holy war reverberated throughout the global English-speaking Muslim community and his broader message of hatred for the unbelievers, especially Westerners, is among the reasons that the self-styled caliphate attracted more than 30,000 foot soldiers from dozens of nations.

What’s more, Awlaki’s message of “self-starter” violence against the West has outlived him. Ubiquitous on the Internet, al-Awlaki has since his death become the only common thread in a series of terrorist plots. The Times Square bomber Faisal Shahzad and the Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were both inspired by al-Awlaki’s summons to holy war against the infidel. Recent ISIS-inspired attacks on U.S. soil can also be traced back to al-Awlaki. Mateen was a known Awlaki follower and fan of his online “recruitment videos.”

Before killing 14 people with his wife last year, San Bernardino shooter Syed Farook regularly watched al-Awlaki’s lectures with his neighbor.

Underestimating the potency of al-Awlaki’s influence five years after his death would be a tragedy. The continued targeting of jihadists on the battlefields of the Middle East will reduce the terrorist threat, but not eliminate it. In a report released just last week, CEP detailed 88 U.S. and European extremists who have been directly inspired by al-Awlaki’s calls to jihad. That list will surely grow further unless al-Awlaki’s presence on the Internet is rolled back.

That possibility now exists. CEP and Dartmouth computer science professor Dr. Hany Farid have developed a technology, called eGLYPH, which can efficiently find and remove extremist content that has been determined to violate the terms of service of Internet and social media companies. It works like this. Once a person identifies an image, video or audio recording for removal, the algorithm extracts a distinct digital signature from the content, which is then used to find duplicate uploads across the Internet. Once the most noxious al-Awlaki messages are flagged and removed, they would automatically be discovered and removed whenever a subsequent upload is attempted.

With any luck, public demands for tech firms to curb al-Awlaki’s murderous message online will remind them that security is the precondition of liberty. This moment offers a welcome opportunity for Internet companies to back up their oft-expressed commitment to fight terror with deeds. They should seize it.

The Counter Extremism Project Presents

Enduring Music: Compositions from the Holocaust

Marking International Holocaust Remembrance Day, the Counter Extremism Project's ARCHER at House 88 presents a landmark concert of music composed in ghettos and death camps, performed in defiance of resurgent antisemitism. Curated with world renowned composer, conductor, and musicologist Francesco Lotoro, the program restores classical, folk, and popular works, many written on scraps of paper or recalled from memory, to public consciousness. Featuring world and U.S. premieres from Lotoro's archive, this concert honors a repertoire that endured against unimaginable evil.